This Article From Issue

September-October 2019

Volume 107, Number 5

Page 264

Pediatrician Mona Hanna-Attisha of Michigan State University and Hurley Children’s Hospital Pediatric Public Health Initiative was an early whistleblower during the Flint, Michigan, water crisis when she discovered that blood samples from her patients contained heightened lead levels. Her 2018 memoir, What the Eyes Don’t See, details her childhood growing up in suburban Detroit as the daughter of Iraqi immigrants and how her experiences prepared her to confront Flint’s environmental crisis. Hanna-Attisha was alerted to the possibility of lead contamination by a friend, Elin Betzano, who had worked at the Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Ground Water and Drinking Water. Betzano realized that the cost-cutting decision to transition the city’s water supply to the Flint River in April 2014 likely resulted in lead leaching into the drinking water, which prompted Hanna-Attisha to investigate. She spoke to special issue editor Katie L. Burke about her memoir. (The following is an extended version of the print article.)

From What the Eyes Don't See

The title of your book is inspired by a line from Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D. H. Lawrence: “What the eye doesn’t see and the mind doesn’t know, doesn’t exist.” How did that idea become a theme in your book?

If you haven’t thought about something, you’re not going to recognize it as a problem. That was my story. I didn’t know about the possibility of lead in water. I was blind to it for a year and a half. I’ve been taking care of kids with lead poisoning for more than a decade, both from Flint and from Detroit, yet I never knew, in all my training, that there was the possibility of lead in the water.

We also don’t see lead in water. It’s invisible. Because we don’t physically see it, smell it, taste it, we don’t know it’s there. We also don’t see the effects of lead. Lead in pediatrics is well known as a silent epidemic. Kids don’t present acutely with lead issues. It’s something we don’t see for years—if not decades—later, when they have problems with cognition and behavior.

But by and large, the biggest meaning of that title refers to problems that we choose not to see. People had their eyes closed to Flint. Even when we saw those images of brown water coming out of people’s taps, we’re like, “Oh, I don’t believe this. It just can’t be real.”

So much of my work as a pediatrician is addressing those upstream, harder-to-see things that will have a greater impact on the trajectory of a child’s life than any antibiotic I prescribe. Asking about things like poverty, nutrition, violence exposure, school issues, and environmental issues. Asking about water, and keeping your eyes open. These other things that we’re often not trained to recognize and that make us uncomfortable, will ultimately save a child’s life more often than anything else.

How do you see the role of pediatricians in environmental justice?

As a pediatrician, I have literally taken an oath to protect children. Part of our job description is to be an advocate. The trust that families put in me, and in this profession, is overwhelming. It is that trust that drove me to do what I did and continue to do what I do.

I train my trainees, and I was always trained, to speak up for children, to meet with legislators, to advocate for immunizations, and gun control, and all these different things that science tells us protect children.

Our duty as pediatricians is not only in that exam room one-on-one with a patient, but it's also in this larger system space. Many physicians don’t see that type of advocacy as their role, but it is one of the reasons I went into this profession. I very much recognize that my job is as a clinician, an educator, a researcher, and also an advocate, and I wear these many hats. Not everybody has to wear all these hats all the time, but we have them in our toolkit, in our doctor's bags, and we can put them on at different times.

My biggest lesson to medical students and to those who want to go into medicine is that we have to make sure that our patients have the healthiest lives possible.

Flint’s water never should have gotten to a point where a doctor had to step up and say that children were in harm’s way. It should have stopped when that first mom held the jug of brown water. But the fact that finally things did change when the doctor stood up and said something is a reminder that this profession still has a lot of credibility and a lot of clout.

It’s important for doctors, academics, scientists, professors, and whomever to get out of our cozy establishments and really get into the uncomfortable spaces, which are our communities, our state capitols, or whatever, to speak up for what’s best for the communities that we’re privileged to serve. I hope that this story enables others to recognize that they also have incredible power, to open their eyes, and to make a difference in their communities.

One of the reasons I wrote this story is to highlight that it is not an isolated story. The Flint story is about deeper, national crises: environmental justice issues, disrespect for science, deteriorating infrastructure, and how we fundamentally care for one another.

In reading your memoir, I was struck by how fortunate it was that you had key people in your life with the necessary expertise to help. Your high-school friend, Elin Betzanol, had been an engineer at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency during the 2003 water crisis in Washington, DC. And engineer Marc Edwards, who was the whistleblower for that crisis as well as this one, also shared his insights with you. Plus you have a history in your Iraqi-American family of fighting injustice here and abroad.

So much of my story is serendipity, like having a high school friend who happened to be a drinking water expert, who happened to be at my house in Atlanta. I mean, are you kidding me? Elin and Marc provided the only playbook that we had. I was learning through them and their experience.

I don't want to say it was all serendipity, because there is so much to be said about being prepared. I started out as an environmental activist and environmental health researcher, and I knew what environmental justice was. To tackle these complicated social, environmental, public health problems—which we are going to continue to face—we need more folks who know their community’s history and who've had, for example, media training and advocacy training. I was the right person, at the right place, with the right team, and the right training, and the right background, at the right time to be able to do this work.

How did your life in Flint help you navigate the lead-in-water crisis?

I've been in Flint for a while. I was first there as a medical student, and then I was in Detroit for about 10 years, where I did my training. I came back to Flint in 2011. There's so much history in my book. There's Flint history, lead history, public health history, and family history. And that history, especially the Flint history, is so critically important because it translates into the everyday. Not just the acute history of this crisis, but the history of General Motors, and the auto unions, and the resistance, and the brave work. The loyalty and the pride that was evident back then is still evident in the everyday community of Flint.

Flint is a really special place. It's a place where this crisis happened and people rolled up their sleeves, and they came together to make sure the kids have the brightest future possible. And that is rooted in Flint's history, a history of innovation, leadership, resilience, resistance, and solidarity. You have to kind of know the history to understand the people who are there and what is important to them.

Barbara Aulicino

How do you see the future of water?

Before Flint, a lot of us, including myself, had almost a naivete about being able to turn on our tap and guarantee that the water is safe and clean. Since Flint, the nation has awoken to the idea, and the recognition that maybe our regulations need to be strengthened. And maybe when we do turn on our tap, we have to question what’s coming out.

Since Flint, there’s been community after community, school district after school district, coming up with innovations and advocacy at the local, state, and national levels. The issue regarding lead in water, which Flint brought to light, also highlighted PFOS [Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid, formerly the key ingredient in the fabric-protecting product Scotchgard] issues and other contaminant issues.

PFOS and PFOA [Perfluorooctanoic acid, used in the production of Teflon] are both flame retardants, but they are also endocrine disrupters that have been increasingly found, not only at military sites, but also in other postindustrial sites. Michigan has the largest number of currently identified sites, but it’s also found in upstate New York, in Pennsylvania, and all over the place. I see these as Flint ripple effects. There’ve been so many positive things that have come out of Flint, such as this awakening to our responsibility and commitment to the future of safe drinking water.

Have your experiences with this particular environmental injustice changed the way you teach your medical students?

It has reaffirmed what I teach my trainees. We’ve always known of the concept of environmental injustice. For example, lead has always been a well-known form of environmental racism. Currently poor, predominantly minority communities are struggling with access to and affordability of safe drinking water. Before the water crisis in Flint, when we recognized that our water was contaminated, it was a water affordability issue.

People of Flint were paying the highest water rates in the country, and in Flint and in Detroit, there were issues with shutoffs. More utilities are looking at water as a commodity. We can’t have a discussion about the future of water without a discussion about the affordability of that water.

Since the Flint water crisis, has the affordability issue been addressed?

It’s not fully addressed in Flint. There have been many different task forces and committees that have looked at water rates. When Flint finally did commit to staying on Great Lakes water, the new water authority called the Great Lakes Water Authority did create some sort of rate assistance program, but it is, by far, not enough to accommodate the needs. Flint has one of the highest poverty rates in the country, and people continue to spend a disproportionate amount of their income on water.

We can’t have a discussion about the future of water without a discussion about the affordability of that water.

Another affordability justice issue that is popping up in other communities is the need to invest in infrastructure and finally get rid of lead service lines. It’s bizarre to think that we’ve had a neurotoxin delivering our drinking water throughout the country. As more and more communities are finally recognizing that we need to dig these up and get them out of our underground bridging water infrastructure, a lot of communities are charging people to replace the private side of that service line. For example, Newark, New Jersey, is in the midst of a very similar lead-in-water crisis. The citywide action level was close to 70 parts per billion, but they were charging the residents who want to get their lines replaced. That becomes a justice issue, because folks cannot afford to have that pipe replaced. So it’s going to be, once again, the privileged and the affluent who have the ability to get safe drinking water.

Flint experienced a big breach of trust in institutions meant to protect us. How has that changed the way you think about the public’s relationship with these institutions and rebuilding trust?

This community-wide trauma obviously was about drinking water and lead, but by and large it was a trauma of trust. People were betrayed by every level of government that was supposed to protect them. How is that trust rebuilt? A long-term commitment, which has yet to be garnered.

That trust is also going to be rebuilt with accountability, which is also in process. Trust will be rebuilt when the accountability is achieved, when there’s some form of restorative justice, some sort of damages, reparations, whatever you want to call it.

I was recently at a conference of philosophers. Somebody asked a similar trust question, and a philosopher said, “Maybe trust shouldn’t be rebuilt. Maybe we should have a healthy dose of mistrust.” I think there’s something to be said for that perspective. Maybe then we’d ask questions and hold people accountable.

You emphasize the importance of resilience in Flint. What do you mean?

Resilience is an increasingly recognized concept, especially in pediatrics. Kids with resiliency—innate or nurtured—can potentially mitigate adversity. Resilience can be built through positive interventions, be it with parenting support, home visiting programs, coaching and tutoring, or other science-based approaches. And those are the types of interventions that we’ve put in place, and also then been able to evaluate and disseminate.

My goal is that Flint is remembered not for this crisis but for its resistance, and also for the hope that we’ve been able to bring for our kids. That’s what my public health initiative is all about. I don’t use the word hope lightly. The hope that we are building is real, tangible interventions that we've been able to put into the city of Flint, such as brand new childcare centers, school health services, Medicaid expansion, nutrition services, literacy programs—the list goes on and on of the awesome, hopeful, evidence-based interventions that are now in Flint. And the really neat thing is, we are exporting that hope.

A quick example: My pediatric clinic is on top of the farmer's market. The community has huge nutrition issues. At the clinic, we give out nutrition prescriptions to every kid to address some of the food security issues. That nutrition prescription includes a $15 voucher, which they fill at the farmer's market. And we robustly evaluate this program as academics.

Our U.S. senator, Debbie Stabenow, who's a big advocate for children and for Flint, has visited our clinic. She put a nutrition prescription program in the 2018 U.S. Farm Bill, which passed Congress, was signed by the president, and now is a $25 million national program, that can potentially touch kids all over this nation. That's just one example of the hope that we have built that has now kind of rippled throughout the country.

Flint is this crazy story of the consequences of science denial. It’s also a story where science spoke truth to power and helped expose a crisis. And then, in our recovery, we are leaning on that emerging science of resilience to mitigate the impact of this crisis.

You start and end your book talking about your grandfather, Haji. What is his significance to this story?

I think it is a surprise to a lot of people when they read my book, because they expect that they're just going to read about Flint, and they say, ”What's all this weird family history stuff in here?” But my family was impossible to separate from the story, including the stories of my grandfather. When I started to write, I wanted the book to be only about Flint, but with our current political climate and the anti-immigration movement, it became increasingly important for me to include that family history. To understand what I was doing and why I was doing it, you have to know who you are and where you came from.

My family history has social justice roots. For example, my Great Uncle Nuri [Nuri “Anwar” Rufail] fought in the Spanish Civil War, and my distant relatives came to Iowa in the 1900s to fight public health issues. It was important to share those stories, including the stories of my grandfather, to say, “Here are the people who are on one of [President Donald] Trump's travel ban lists. People who have roots in social justice, and who care about opportunity and freedom and democracy. They are in all of our communities, trying to make them a better place.”

At the start of your book, Haji gives you your name, Mona, which means hope. And then you end with a sense of hope. How are you thinking about hope and the Flint crisis?

I often say that I am literally writing these prescriptions for hope. And that has been my mantra ever since I was a kid. I was always an optimist, and wherever I am, I’m trying to make the world a better place. Those values were instilled in me as a child. That is what I am trying to bring about every day in Flint—to make this place brighter than it ever was. To turn this crisis around and so Flint serves as a model for hope for the rest of the nation.

Related American Scientist Content

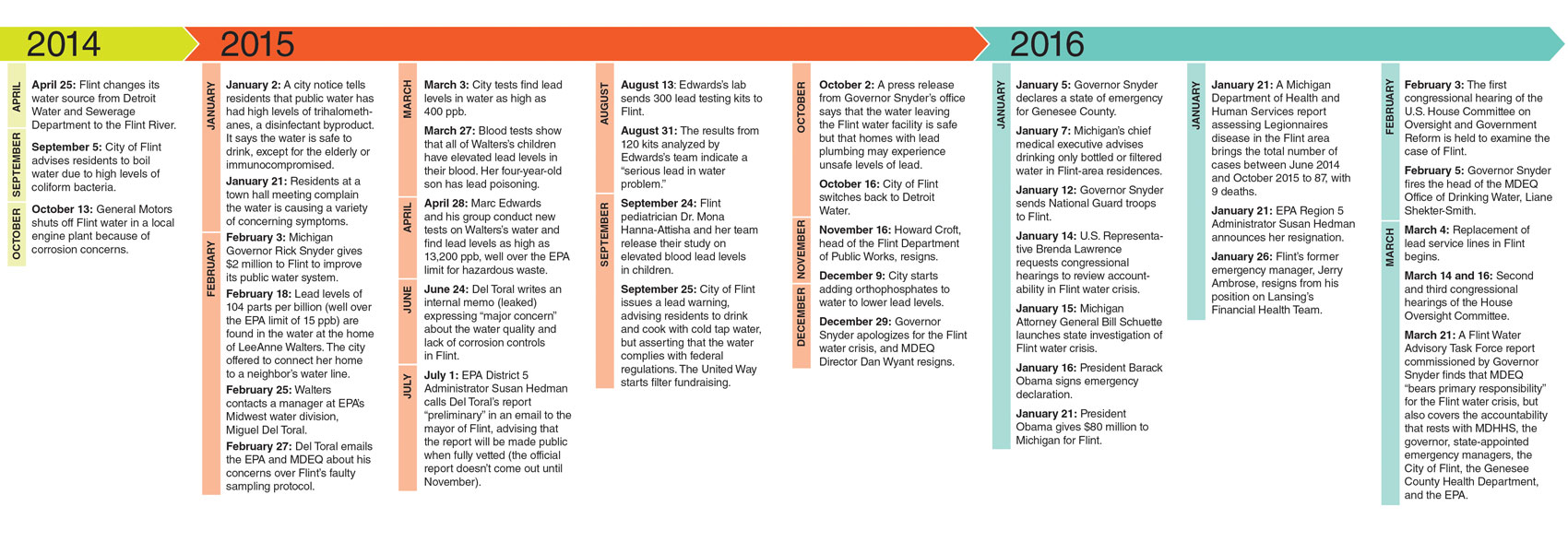

- Burke, K. L. May–June 2016. First person with Siddhartha Roy: Moving forward after Flint. [Includes timeline and link to related podcast.] https://www.americanscientist.org/article/moving-forward-after-flint.

- Burke, K. L. May–June 2016. First person with Marc Edwards: Flint water crisis yields hard lessons in science and ethics. https://www.americanscientist.org/article/flint-water-crisis-yields-hard -lessons-in-science-and-ethics.

- Roy, S. Janurary–February 2017. The hand-in-hand spread of mistrust and misinformation in Flint. https://www.americanscientist.org/article/the-hand-in-hand-spread-of-mistrust-and-misinformation-in-flint.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.