This Article From Issue

March-April 2023

Volume 111, Number 2

Page 76

In this roundup, managing editor Stacey Lutkoski summarizes notable recent developments in scientific research, selected from reports compiled in the free electronic newsletter Sigma Xi SmartBrief.

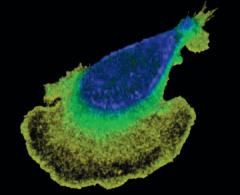

Viral Invasion

Advanced microscopy techniques provide an unprecedented look at the early stages of virus–cell interactions. The processes by which viruses spread through populations and the ways in which they infect cells are well-trodden areas of research, but the period between exposure and infection has proven more difficult to study. Viruses zip through extracellular space at high speeds, and the difference in scale between the tiny pathogens and the comparatively large cells makes it difficult for microscopes to focus on both players in the process. Chemists at Duke University have developed a method that divides and conquers: One laser-equipped microscope follows a fluoresced virus, while a second, 3D microscope focuses on the cells. Video combining the two feeds shows the virus surfing on the protein layers of cells as it looks for weaknesses in their defenses. The technology can track the virus for several minutes, but the fluorescence wears off before the virus makes its entry into a cell. The team is developing methods to extend the tracking period so that they can follow the process from beginning to end. Information about the period between exposure and infection could present new opportunities to stop pathogens before they begin damaging cells.

Johnson, C., J. Exell, Y. Lin, J. Aguilar, and K. D. Welsher. Capturing the start point of the virus–cell interaction with high-speed 3D single-virus tracking. Nature Methods 19:1642–1652. (November 10, 2022).

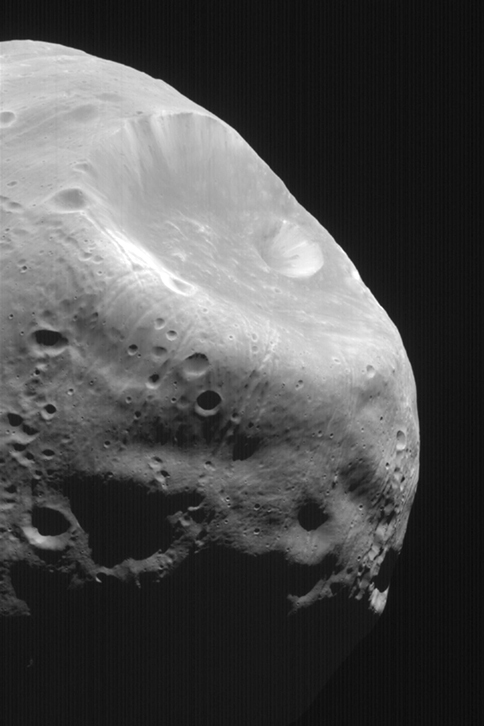

Mars’s Groovy Moon

Striations on the surface of Phobos might be signs that the Martian moon is fracturing. Phobos, the larger of Mars’s two moons, is 27 kilometers across and orbits less than 6,000 kilometers above the planet. Its path is spiraling inward about 1.8 centimeters per year, on a course toward eventual destruction. Computer simulations suggest that the long, parallel grooves that cover Phobos may be caused by Mars’s gravity starting to rip the satellite apart. Previous studies had suggested that the striations were caused by an impact, and that the grooves could not have resulted from Mars’s gravity because the moon’s loosely packed exterior would have refilled the indentations. A team led by aerospace engineer Bin Cheng of Tsinghua University in Beijing created a new model of Phobos with a fluffy exterior but a dense interior. In their simulation, the researchers found that tidal forces from Mars could be creating the grooves, which means we may be witnessing the end of Phobos. In 2024, the Japanese Space Agency plans to launch a new mission that will land a spacecraft on Phobos. Samples gathered during that expedition should provide more information about the history and fate of this puzzling little moon.

NASA/JPL/Malin Space Science Systems

Cheng, B., E. Asphaug, R.-L. Ballouz, Y. Yu, and H. Baoyin. Numerical simulations of drainage grooves in response to extensional fracturing: Testing the Phobos groove formation model. The Planetary Science Journal doi:10.3847/PSJ/ac8c33. (November 4, 2022).

Motives for Mongolian Raids

Tales of hordes led by Attila the Hun invading Asia and Europe are legendary, but the reasons behind these incursions may have had more to do with climate pressure than with bloodlust. Evidence in tree rings indicates that the most brutal Hunnic raids coincided with periods of extreme drought, which may have resulted in economic instability and desperate attempts to obtain food and other resources. The Huns’ attacks on the Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries CE are often framed as a battle of barbarism versus civilization. Archaeologist Susanne E. Hakenbeck and geographer Ulf Büntgen, both of the University of Cambridge, sought to complicate this narrative. They examined both groups’ material cultures, practices, and diets and found signs of an active exchange between the Hun and Roman communities. But if the two groups coexisted and traded with each other, what led to the brutal and destabilizing raids? Hakenbeck and Büntgen found their answer in trees. Carbon and oxygen isotope data from oak tree rings showed clear indications of droughts during the years 350 to 500. The summers from 420 to 450 were particularly dry—the same period as Attila the Hun’s most aggressive raids. This environmental evidence gives context to the seemingly senseless violence. It also raises alarms for the future as modern climate change increases the frequency of droughts, resulting in new generations of desperate populations.

Hakenbeck, S. E., and U. Büntgen. The role of drought during the Hunnic incursions into central-east Europe in the 4th and 5th c. CE. Journal of Roman Archaeology doi:10.1017/S1047759422000332. (December 14, 2022).

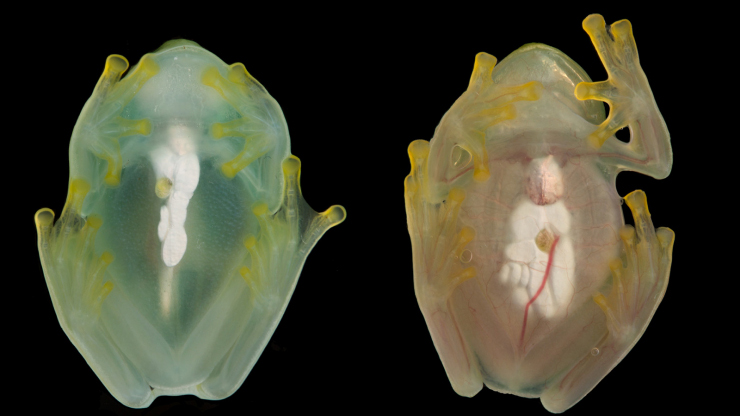

It’s Not Easy Being Clear

Sleeping glassfrogs take camouflage to the next level by hiding their red blood cells and becoming nearly transparent. Hyalinobatrachium fleischmanni are nocturnal, arboreal frogs that live in Central America. The frogs’ skin and muscles are translucent, making their bones and organs visible to the naked eye. When awake the frogs have a reddish tint, but they lose all color and become clear when they fall asleep. A team of biomedical engineers investigated the mechanics behind this change and found that the sleeping frogs hide their red blood cells in their livers. With their vascular systems cleared of color, the frogs can safely spend their days asleep in leaves, where their clear bodies barely even cast a shadow for predators to track. The researchers used photoacoustic microscopy, which bounces ultrasonic waves off of light-absorbing molecules. They found that when the frogs slept, they had an 80 to 90 percent drop in circulating red blood cells, and that those cells were instead confined to the liver. imilar cell packing in humans would result in blood clots. Studying the mechanisms that allow glassfrogs to concentrate their red blood cells may help researchers develop new anticoagulant treatments.

Jesse Delia

Taboada, C., et al. Glassfrogs conceal blood in their liver to maintain transparency. Science 378:1315–1320. (December 22, 2022).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.