Darwin's Literary Models

By Keith Thomson

It may not be structured like a journal paper, but On the Origin of Species was written according to classical rules of rhetoric

It may not be structured like a journal paper, but On the Origin of Species was written according to classical rules of rhetoric

DOI: 10.1511/2010.84.196

In David Lodge’s great comic novel of academic life in the long-distant days of 1969 and 1970, Changing Places, members of the English department at Euphoria State University play a typical intellectuals’ game: humiliation. Each player must admit to having not read some canonical work in their field; for example, to have not read Mrs. Gaskell’s Cranford would earn fewer points than Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Too many biologists, sad to say, could win this game by producing their own ace—Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Everybody has a copy, but, like Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time, the work is rarely read from cover to cover.

American Philosophical Society

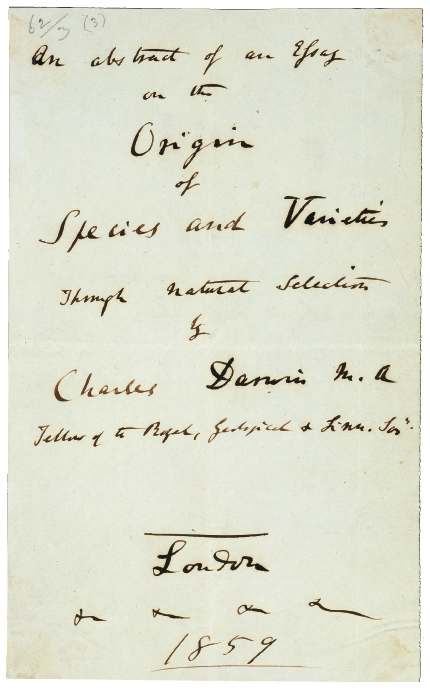

Darwin originally hoped that his great masterpiece, published in 1859, would be titled An abstract of an Essay on the Origin of Species and Varieties Through Natural Selection. As is well known, the book was written in great haste after Alfred Russel Wallace seemingly scooped Darwin by arriving at just the same idea. Darwin was forced quickly to digest the work he had pursued for the previous 20 years into a (relatively) short book, and we are all the winners for that. Under its final and even longer title, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, the book is a lucid exposition of his theory and far more influential than the obsessively detailed work that he originally intended to write would ever have been.

Those who, in this past bicentennial year of Darwin’s birth and sesquicentennial year of the publication of the Origin, have taken the time to study the book carefully may have noticed an oddity of its structure. It is quite unlike most scientific books of its time, or of ours, in the development of its subject. As Darwin explained both in his final chapter and his later Autobiography, the 501 pages of the Origin were composed as “one long argument,” and, like everything Darwin did, it was carefully calculated. Philosophers and logicians have, therefore, long been interested in Darwin’s rhetorical method.

Darwin’s other books—such as The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs, (1842), The Various Contrivances by Which Orchids Are Fertilised by Insects (1862), The Movements and Habits of Climbing Plants (1865), The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms (1881), and even his controversial The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871)—follow what seems to be a more conventional format. First the facts are laid down, then the various rival explanatory theories are laid out, and finally Darwin gives his own ideas. The approach can be seen particularly clearly in Darwin’s Coral Reefs.

The first thing that is different about the Origin is that the title contains a one-sentence précis of its conclusion. Right on the cover, Darwin defines natural selection (a new term for his readers) as “the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life.” But the book is different from Darwin’s others principally because of the way in which he makes his “long argument” and, in fact, because it is an argument—an exercise in formal rhetoric—rather than an analysis or an exposition.

Since Francis Bacon’s time (particularly since the publication of The Advancement of Learning in 1605), methods of scientific discovery have been categorized as some variant of either deductive (proceeding from the general to the particular) or its opposite, inductive. Method, however, is not the same as exposition. A piece of science might be created in one mode but be much better explained in another. In terms of rhetoric, the modes corresponding to deduction and induction were, respectively, synthetic and analytic. Coral Reefs is written in the latter, analytic mode. The Origin hews more closely to the synthetic, in which the author first lays down a central proposition and then presents more and more arguments to extend and confirm it.

Students of science today, and likely their mentors as well, are not schooled in the subtleties of logic and rhetoric. The composition of a scientific paper follows very simple conventions—woe betide anyone who submits a paper to a peer-reviewed journal without following the prescribed rules faithfully. Things were different in Darwin’s day; styles of writing about science ranged from the mathematically precise to the discursively narrative. But that is not to say that there were no rules or models: On the contrary, in the late 18th century and early 19th century, attention to rhetoric and logic flourished.

The standards were high. In his 1687 Principia Mathematica, Isaac Newton had pronounced his famous four rules for reasoning, of which the first is the most famous and influential: “We are to admit no more causes of natural things than such as are both true and sufficient to explain their appearances.” Closer to Darwin’s time, the most influential works included Joseph Priestley’s A Course of Lectures on Oratory and Criticism (1777), John Locke’s essay Of the Conduct of the Understanding (1706), Lord Kames’s Elements of Criticism (1762) and William Duncan’s The Elements of Logick (1748), all of which still make fascinating reading today. Among the most widely read and influential of all was Hugh Blair’s Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres (1784). And all rhetorical style traced back to, and reacted against, the classics, particularly the works of the great Roman orator Marcus Tullius Cicero. As Darwin was a superbly well-read intellectual, it is natural to ask, with respect to his “long argument,” where did he stand in relation to this great literary tradition? The question has fascinated historians and philosophers of science. Among the most notable contributors to the discussion are Martin Hodge at the University of Leeds, Matti Sintonen at the University of Helsinki and Doren Recker at Oklahoma State University.

Darwin specifies the pattern of his argument in the introduction to the Origin. First he establishes a key premise: Artificial selection of varieties of plants and animals would be its central analogy (chapter 1). He then documents variation in nature (chapter 2) and follows with the mathematical imperatives of population biology and the “Struggle for Existence,” which combine to produce natural selection (chapter 3). He brings all of these topics together in chapter 4 and introduces the concept that transmutation of existing varieties of organisms into new species “almost inevitably causes much extinction of the less improved forms of life, and induces what I have called the Divergence of Character.”

These four chapters contain his idea in a nutshell. He extends it in chapter 5 with discussion of “little known laws of variation and of correlation of Growth.” But then, instead of pressing on directly with his case, he makes a detour into four chapters in which “the most apparent and gravest difficulties on the theory” are admitted and dealt with. Only after putting the whole affair into a geological context (chapter 10) is he ready to deal with corroborating elements of his theory—such as geographical distributions, homology, vestigial organs and (one of the strongest parts of his argument) the fact that a pattern of descent explains the patterns of similarity long since formalized in systems of classification (chapters 11 through 13). At last, there is a final summing up and some rather lyrical “concluding remarks.”

In the synthetic mode of deductive rhetoric, the most effective argument is often syllogism: If all A are B, and all C are A, then all C are also B. Darwin’s “long argument” has the character of an extended syllogism: Variation can be artificially selected by breeders to produce new forms; variation exists in nature; the mathematically driven struggle for life is comparable to the ruthless hand of the breeder; there have been vast eons of time within which natural selection could operate; therefore natural selection explains both origins and extinctions within organic diversity. The order in which Darwin developed his subjects is, however, different from the patterns originally laid out in his Sketch of 1842 and Essay of 1844, particularly with respect to the position of the “difficulties” discussion in chapters 6 through 9.

Darwin was quite self-effacing in his introduction, explaining to his readers that the book would necessarily seem imperfect, and that he could not “give references and authorities for my several statements; and I must trust to the reader reposing some confidence in my accuracy.” This was a remarkable assertion for someone who was proposing to lay out a revolutionary idea that he could not definitively prove. In the same vein, in his first chapter, on “Variation in Nature,” he announced that there would be no space to give “a long catalogue of dry facts.”

Missing from the whole book is any introductory section laying out in detail the problem to be addressed. Darwin seems to have assumed that his readers would be perfectly familiar with the notion of transmutation of species, “the mystery of mysteries, as it has been called by one of our greatest philosophers” (referring to John Herschel). On his third page he cited Robert Chambers’s Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844), which suggests that this assumption was the case. But Darwin did not use his vast knowledge of plant and animal diversity and distribution to establish initially, through examples, that transmutation was a phenomenon seeking an explanation. Instead, he steadily built up an “argument” almost, as it were, from the other end, carrying the reader along until even the most recalcitrant must (he hoped) be persuaded.

During his final months at Cambridge, Darwin read and was greatly impressed by John Herschel’s Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy (1830). In it, Herschel lays out the approach to the exposition of scientific ideas known as vera causa, which was derived originally from Bacon and Newton. Establishing the vera causa—true cause—of a phenomenon involves three phases. The potential causal phenomenon has to be real and existing, it has to be demonstrated as capable of producing the effect under investigation, and then it has to be shown to be actually responsible. The last phase is always the hardest, and is actually impossible to realize in investigating a unique historical event that cannot be reproduced for experimental investigation. Hodge has convincingly argued that Darwin laid out the Origin along the lines of vera causa: Chapters 1 through 4 establish the existence of a cause (natural selection), chapters 5 through 13 demonstrate capability, and chapters 10 through 13 demonstrate responsibility.

National Portrait Gallery, London

But Darwin still had to argue his case for a vera causa, and here other models and approaches also may have influenced him. I will single out two. As a student at Cambridge, he had been vastly impressed with what he described as the “long line of argumentation” of William Paley’s Natural Theology (1802). This influential book, which in some ways seems more like a biology textbook than a theological work, proceeded on the synthetic mode of deductive rhetoric via a syllogism. Paley first laid down a premise that seemed irrefutable—that a complex functional device such as a watch requires an intelligent designer and creator. He then demonstrated that organisms are complex and adapted. If the existence of a watch proves the activity of a designer, then even more so does a human, or a bird. The similarity of approach to Darwin’s Origin, which also argues from a powerful analogy (artificial selection), is as striking as the dissimilarity of the two men’s conclusions.

Towards the end of his book, Paley included a section arguing against the contemporary ideas of evolution propounded by Scottish philosopher David Hume, English physician Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles) and French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon. One might ask why this defense was necessary, especially because it drew attention to potential weaknesses in Paley’s argument. The answer is partly that Paley was confident of his ground and partly that “refutation” was formally required. Paley’s “long argument” is an example of the neoclassical dispositio defined by Duncan and Blair, in which a jurist or preacher was instructed to set out in order: introduction, proposition (the question at hand), division (elements of the case), narration (reasoning), argument (refutation of opposing positions), pathetic part (appeal to the emotions) and conclusion. (For Cicero, the roughly corresponding parts had been the exordium, narratio, refutatio, confirmatio and peroratio.)

It is interesting, then, that in the library of the University of Cambridge there is a short note in Darwin’s hand headed “Books that I read my second year at Edinburgh” that lists, among works on medicine and travel, “Blair’s Belles Lettres.” If we look at the Origin from the point of view of rhetorical practice, we see the same convention Blair used: The Origin has its proposition (the congruence of artificial and natural selection) and its narration (chapters 3, 4 and 5). These fit Duncan’s requirement that “those propositions are always first to be demonstrated, which furnish principles of reasoning in others; it being upon the certainty of the principles made use of, that the certainty of the truths deduced from them depends.” The otherwise unusual positioning of chapters 6 through 9 is then made clear: They are Darwin’s refutation. Chapters 11, 12 and 13 are his confirmation. His final chapter even has its pathetic part in the form of the slightly flowery sentiments with which he conjures up the metaphor of the “entangled bank” and glories in the “grandeur in this view of life.”

Right from the beginning, Darwin faced a difficult problem in writing up his theory. As he noted in his Autobiography, he realized early on that it seemed “almost useless to endeavour to prove by indirect means that species have been modified.” Instead he chose (or was forced) to make a logical argument in a form of which Cicero would have been proud. Each part of his theory—variation, overproduction, the struggle for life—was true and demonstrable. The argument was irrefutable. If he had been a mathematician he would have needed only to add one final notation to page 490: Q.E.D. (quod erat demonstrandum).

All of Darwin’s books and manuscripts reveal the extraordinary breadth of his learning. But the Origin was, in every sense, both the most original and the most classical, making it an even more remarkable achievement.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.