Taking a Digital Dive

By Catherine Clabby

A new global survey gets the best look yet at the world’s imperiled coral reefs.

A new global survey gets the best look yet at the world’s imperiled coral reefs.

DOI: 10.1511/2014.108.178

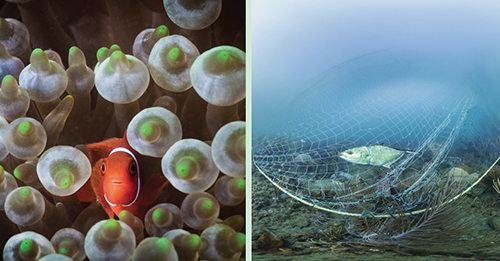

For years, Richard Vevers was exasperated by how few people were aware of the threats to coral reefs, vital habitats built by tiny invertebrates and the symbiotic algae that feed them. A full quarter of all marine species globally depend on tropical reefs as nurseries, food sources, or lifelong homes. That entire ecosystem is in a precarious situation. Nineteen percent of all cataloged reefs have already been destroyed, scientists estimate; 35 percent of what survives could disappear by 2050 due to destructive fishing practices, pollution, and rising ocean temperatures.

Catlin Seaview Survey

Nature photography intended to celebrate the amazing underwater diversity may have inadvertently contributed to the problem. “When people see images they see the nice reefs. There is a perception that is very, very different from the reality,” says Vevers, himself an underwater photographer as well as a marine conservationist.

Catlin Seaview Survey

Vevers decided to update the picture. He recruited friends from the advertising industry, where he used to work, to create a more honest portfolio of both healthy and ailing reefs. His original plan was to compile photos only and share them globally for free. Then an international insurance company, Catlin Group, agreed to fund the project with more than $1 million, if Vevers expanded it to include data with scientific significance.

The result is the Catlin Seaview Survey, developed by Underwater Earth (an Australian nonprofit group Vevers founded) and by marine biologists at the University of Queensland, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and elsewhere. Since 2012 the project has been building up a visual catalog of the world’s shallow reefs (depths less than 20 meters), at a scale and resolution never before attempted.

Catlin Seaview Survey

Photographers, researchers, and students conducting the Catlin survey use three bundled waterproof cameras that fire at once and capture complete, 360-degree underwater scenes every three seconds. Along with dangers such as coral bleaching and debris, the survey has documented much underwater splendor at the Great Barrier Reef, in the Coral and Caribbean Seas, and off Bermuda, the Galápagos Islands, and Monaco. In 2012, Google launched an underwater “street view” that can create custom, virtual dives using imagery from the survey.

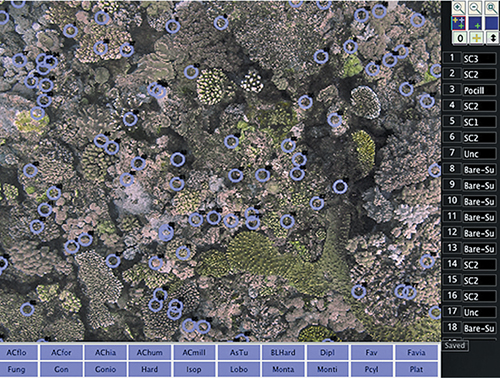

Vevers likes the attention that the beauty shots attract. But he recognizes that the most scientifically significant photos are the less picturesque ones made by the survey cameras that point straight down. Traditionally, marine scientists have assessed corals much the way botanists count plants on land, only in scuba gear: They lay down quadrants, or square frames, on portions of a reef and photograph what lives inside those borders. No more than 250 square meters of healthy, ailing, or dead corals could be documented on each dive. From those relatively small samples, the researchers then extrapolate about a reef’s overall makeup and health.

The Catlin survey records 4,000 square meters of reef per dive, delivering a deluge of data that has created new challenges. Computer vision specialists at Scripps are adapting facial-recognition software invented by the Central Intelligence Agency to count and classify corals in the huge inventory of photos. “Hopefully we’ll get to the point where we can get information from hundreds of thousands of images within six months to a year, rather than 10 years, which is probably what it would take if you did it manually,” says David Kline, a Scripps coral reef biologist affiliated with the survey.

This spring, the survey began work in biodiversity-rich waters off the Philippines. Marine scientists planned to look for signs of damage from crown-of-thorn starfish, coral predators that live on reefs. The starfish don’t normally cause lasting harm, but their populations can swell to destructive levels in places where fertilizer and other nutrients wash from land to sea. Catlin survey cameras may also document damage caused by trash, boat groundings, and illegal fishing.

In keeping with Vevers’s original vision, the survey data are being made available for free online, posted at the Catlin Global Reef Record (http://globalreefrecord.org). The image bank should help conservationists locate thriving reefs that are good candidates to safeguard in new marine preserves, says Manuel González-Rivero, a Queensland postdoctoral researcher coordinating the shallow reef survey. The photos may also help identify which corals are most resistant to habitat degradation.

One welcome surprise from the Catlin project is that it is stirring hope, despite its abundant evidence that people are harming reefs. “Yes, we are impacting the reefs,” says González-Rivero, “but there still are areas with great potential to be protected.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.