This Article From Issue

September-October 2023

Volume 111, Number 5

Page 310

The Deepest Map: The High-Stakes Race to Chart the World’s Oceans. Laura Trethewey. 304 pp. Harper Wave, 2023. $32.00.

In her latest book, The Deepest Map: The High-Stakes Race to Chart the World’s Oceans, award-winning environmental and ocean journalist Laura Trethewey documents the urgency to explore undiscovered ocean expanses and map the seafloor. Although the ocean covers more than 70 percent of our planet, just 25 percent of the Earth’s seafloor is mapped. To describe the scope of this problem, the overused phrase “we know more about the surface of the Moon and Mars than we do about our own seafloor” is commonly tossed around ocean science circles. However, detailed maps of the Earth’s seafloor, and changes in its shape, are critical for safe navigation, trade, and global supply chains. Seafloor maps provide key insight into marine hazards such as earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions. Such maps are also important for exploring seafloor resources that may fuel innovation in everything from electric vehicles to pharmaceutical industries.

Considering climate-driven oceanic changes, increased interest in mining the seafloor, and a growing population of more than 8 billion people who rely on healthy oceans, we need 100 percent of the Earth’s seafloor mapped, and we need it now. The Nippon Foundation-GEBCO (General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans) Seabed 2030 Project, typically referred to as Seabed 2030, is a current global initiative to map the entirety of Earth’s seafloor by the year 2030. Trethewey explores the opportunity that Seabed 2030 and a global map of the Earth’s seafloor provides, the arduous task of producing it during this decade, and some surprising consequences should it fail.

She details the Five Deeps expedition that took place in 2018 and 2019, during which private equity investor and world explorer Victor Vescovo became the first person to dive in a submersible to the deepest parts of all five oceans: the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Arctic, and Southern. To complete such an impressive feat required a support team of scientists and engineers, and, most importantly, a substantial mapping effort to determine the deepest location in each ocean basin.

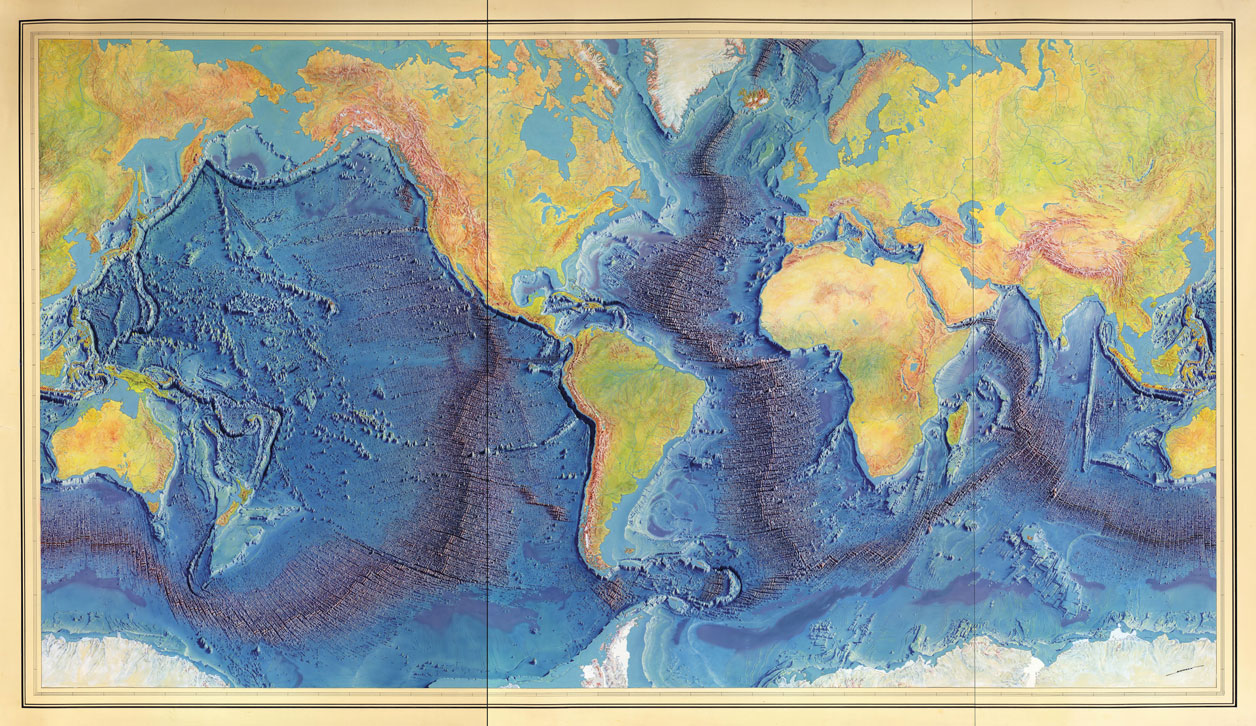

If you Google “global seafloor map,” you’ll find dozens of images showing depth variation or bathymetry of the Earth’s seafloor. Such results give the illusion of completion, of a comprehensive map of the global ocean basin. However, these images are not maps, but rather, predictions of seafloor depth, estimated from subtle changes in satellite measurements of gravity. Although satellite gravity measurements provide an excellent tool for predicting bathymetry, they do so at a resolution that is seldom practical for any real-world application, and certainly not for determining the deepest point in each of the world’s oceans. Today, reliable seafloor maps are produced aboard survey vessels using sonar. Just as bats use sound for navigation through the process of echolocation, humans use sound to determine the distance from a specialized sonar system on a vessel to the surface of the Earth’s seafloor.

Without mapping target locations for the deepest depths and determining their locations in each ocean basin, Vescovo’s record was at risk of being surpassed by future ocean explorers who might have access to better bathymetric maps. He needed a hydrographer—someone who measures ocean depths and maps underwater topography—to map the seafloor, plan his dive sites, and validate his records. That’s where Cassie Bongiovanni, a recent graduate with a master’s degree in ocean mapping, came in. During the roughly yearlong Five Deeps expedition, Bongiovanni mapped an area half the size of Brazil and determined the deepest locations in all the world’s oceans: 8,376 meters in the Atlantic Ocean, 7,434 meters in the Southern Ocean, 7,192 meters in the Indian Ocean, 5,550 meters in the Arctic Ocean, and 10,925 meters at the Challenger Deep in the Pacific Ocean—the deepest place on Earth. Not only did Bongiovanni’s work enable Vescovo to become the first person to verifiably descend to the deepest parts of each ocean, she also contributed significant new maps of previously unexplored regions to the Seabed 2030 initiative.

From Library of Congress Geography and Map Division.

Mapping the entirety of the seafloor is no small feat. The oceans are unfathomably large, remote, and often hostile to the hydrographers responsible for mapping them. Such an initiative requires extraordinary resources: time, money, vessels, survey equipment, and specialists. Even when such resources are available, conditions at sea often lead to lost time and subpar data. Trethewey reveals widespread concern about the task of mapping the entire ocean basin by the end of the decade, and explores potential catalysts for success, such as high-tech unmanned surface vessels (USVs) that are capable of mapping large swaths of the seafloor with limited human intervention, or crowdsourcing maps in remote regions, where local communities may benefit the most from a novel map of their coastal waters. Achieving a global map of the seafloor by the year 2030 is a situation requiring collaboration, international cooperation, and every available resource. The task is daunting and the time line short, but the consequences of mapping at a comfortable pace are immense.

This urgency is apparent when Trethewey travels to the remote Inuit hamlet of Arviat, on the mainland of Nunavut, where people are strongly reliant on coastal waters for food. Although sea level is rising in many places around the globe, here the land is moving upward in a process known as glacial rebound, and as a result, sea level has the appearance of falling. Inuit people have relied on elders in the community for navigation advice in coastal waters, but with recent shoaling, or changes in the shape and behavior of the waves as the water depth decreases, community leaders are no longer able to confidently determine the shape of the seafloor and help vessels safely navigate. After several fatal boating accidents, the community of Nunavut requested mapping support and are now being trained to map and monitor their own waters to avoid future preventable wrecks. In another example, Trethewey participates in archaeological excavations in Florida’s coastal waters, where sea level rise has led to land loss and flooded cultural sites. As the sea level continues to rise, archaeologists are concerned that more sites will be lost. Without improved maps, these sites may be lost forever.

The task is daunting and the time line short, but the consequences of mapping at a comfortable pace are immense.

Although mapping the seafloor has historically been a project undertaken by academics and community leaders such as those Trethewey visited, there are larger, more powerful groups with special interest in seafloor mapping for reasons that include everything from industrial exploitation to national defense. Trethewey attends meetings of the International Seabed Authority and the GEBCO Sub-Committee on Undersea Feature Names (SCUFN), where she sees firsthand how nations can improve their political position by mapping their coastal waters, and by naming and claiming the seafloor. A nation’s exclusive economic zone, over which they have jurisdiction for exploration and exploitation, extends 200 nautical miles (about 370.4 kilometers) off the coast. Improved maps have the potential to help expand an exclusive economic zone, and thus a country’s borders. Even naming a newly mapped feature on the seafloor in international waters has the potential to help a nation extend their political reach. Nothing about the oceans is apolitical, adding yet another layer to scientific exploration.

In The Deepest Map, Trethewey braids her personal experiences and observations from joining expeditions of uncharted waters with reportage on and interviews with various stakeholders in ocean mapping, as well as Bongiovanni’s journey mapping the deepest extremes of the world’s oceans for Vescovo. She thoughtfully untangles the often overlooked and poorly understood needs for expanded seafloor maps, and makes the case that mapping the seafloor is indeed a high-stakes race against climate change, mining, and the reach of human influence. The book provides a glimpse into one of science’s and society’s greatest challenges—mapping the entirety of the Earth’s seafloor—from a diversity of perspectives that highlight the complexity and necessity of this task, in a way that is accessible and interesting to both scientists and lay readers.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.