Comments and Corrigenda in Scientific Literature

By Joseph Grcar

How self-correcting is the written record of scientific and engineering endeavors?

How self-correcting is the written record of scientific and engineering endeavors?

DOI: 10.1511/2013.100.16

Because human knowledge is by definition fallible, correction remains a necessity. An understanding of how error correction works in the scientific literature helps rebut fears that the veracity of the literature is declining and may suggest changes to enhance the correcting process.

Illustration by Barbara Aulicino.

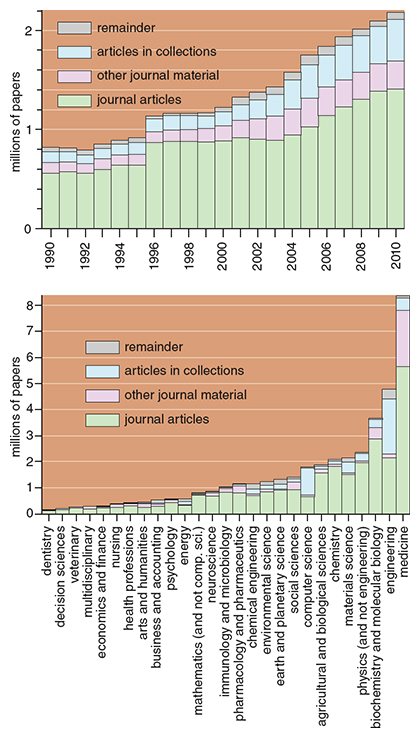

Scholarly publishing has a relatively short history in its present form. It is interesting to note that journal articles have explicitly referenced other articles only since the mid-19th century, thereby enabling citation impact factors—lamentably, some might say. The first large tranche of about 400 journals were founded in the latter part of the 18th century around the time of the American Revolution. Many early journals published articles on any subject, but they restricted submissions to members of a royal academy (which served as a kind of peer review) or to faculty of a university (which traded its journal gratis with other schools, a continuing practice). The modern research university with a comprehensive library of current publications developed in the 19th century. As these universities employed growing numbers of increasingly specialized researchers, they created audiences for the journals that predominate today: addressing a single discipline and drawing submissions from authors not affiliated with the publisher. About 2 million articles were published in the whole 19th century, while roughly that number have been published annually in recent years (see the top graph, above).

It comes as no surprise that the scientific literature contains mistakes, because an integral aspect of scientific research is to cope with errors. The types of possible mistakes vary with the purpose of the work. Thomas Kuhn identified three activities in science per se: establishing facts, reconciling facts with theory and articulating theory. A similar spectrum of work occurs in research into engineering processes or medical treatments. All these activities involve choices that are susceptible to error. For example, measurements are subject to fluctuations, and phenomena generally must be observed indirectly, so the quality of the selected data may be poor, or the chosen transformation of the data to the quantity of interest may be inappropriate.

Sidney Harris.

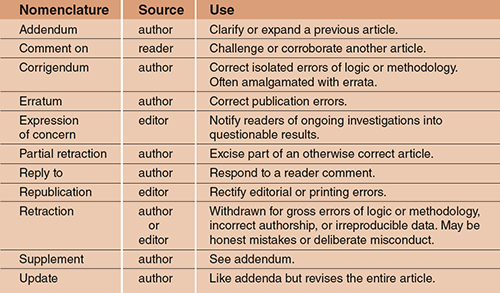

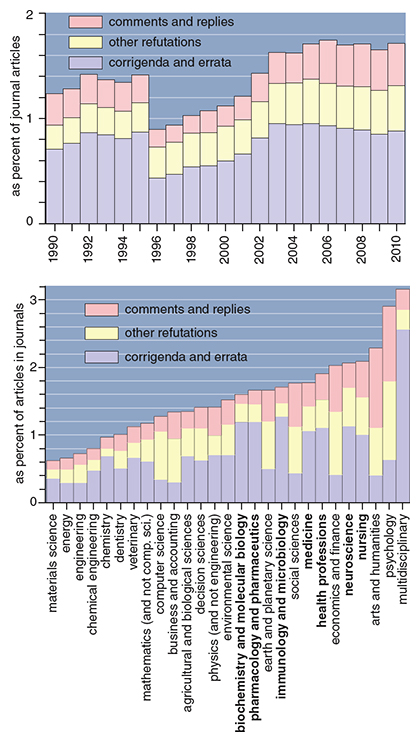

Scholarly journals exhibit a variety of responses to errors in research articles (see the table below). The peer review process undoubtedly detects some errors but journals supply little information about rejection rates and reasons. (Acceptance for publication depends on correctness, relevance and significance. Reviewers offer opinions about the correctness of articles, but they cannot be expected to duplicate the work to be certain.) Authors themselves report the majority of known mistakes and correct them in corrigenda and errata (see the top graph further below). Errors found by readers may appear in formal “comment on” and “reply to” exchanges. Identifying errors in complicated reasoning is itself a type of research that may result in separate articles. For example, the present article disputes the sometimes-pessimistic assessment of scientific error rates by supplying more data and a broader context. Finally, evaluating the merit of data and theories is intrinsic to scientific discourse. In recent decades the annual incidence of all three types of corrections (corrigenda and errata, comments and replies, and other disputatious material) has been nearly constant at about 1.6 percent of full-length journal articles, which at present amounts to almost 25,000 corrective articles per year.

Illustration by Barbara Aulicino.

It is misleading to impugn the scientific literature by focusing on fraudulent research as the Wall Street Journal did in 2011. Forced retractions number only a few hundred annually by the newspapers’s own estimate, which is vanishingly small compared to the tens of thousands of corrections. Some retractions do involve fraud that can be difficult to prove. However, the journal did not explain that many retractions are prompted by simpler chicanery such as plagiarism or unapproved authorship. These transgressions are easier to notice now that documents are available through electronic media, which may account for the recent increase in the still very small numbers of retractions.

Illustration by Barbara Aulicino.

The main issue is whether the present rate of correction is adequate. This question fundamentally concerns the social traditions of editorial boards and research communities because correction rates vary considerably across subject areas (see the bottom graph above). In general, the overall rates of corrections are lowest in engineering (0.5 to 1.0 percent of journal articles), somewhat higher in the sciences (1.0–1.5 percent), and highest in health and social sciences and liberal arts (1.5–2.0 percent). Multidisciplinary journals are outliers on the high end with correction rates over 3.0 percent.

The positive impact of editorial policies may be seen in the uniformly high rates of self-correction in subject areas connected to biomedicine (seven areas with 1 percent corrigenda and errata). These fields have the most experience in formulating discipline-wide correction policies. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors suggests procedures for making each type of correction, and the corrections are consistently indexed by the U.S. National Library of Medicine through the PubMed portal to the MEDLINE database. These policies emphasize that “the editor’s concern should be correcting the literature so the readership can rely on the information published.” Knowledge that journals will routinely publish commentary and corrections may encourage authors to be diligent in correcting their own mistakes lest they be corrected by others.

The view that correction is a normal aspect of scientific publishing may also be a factor in the very high correction rates of multidisciplinary journals. Such journals have traditions of fostering scientific communities through editorials, reviews and sections devoted to commentary from readers. For example, Nature has a correction rate of 5 percent achieved through explicit editorial policies for different types of corrections (addenda, corrigenda, errata, retractions and refutations).

The low rate of correction in engineering literature may be abetted by the manner of publication. Many articles for the engineering sciences appear in conference proceedings (see the bottom graph above). These articles do undergo peer review, and some of the venues are highly selective. Because the proceedings appear infrequently, they do not include corrigenda or reader comments pertaining to the previous conference. The inability to publish corrections for a large part of the literature may contribute to a low rate of reporting errors for articles that do appear in journals.

In summary, the scientific literature is self-correcting though corrigenda and though reader comments. Corrections of various kinds appear at the rate of one to two per hundred journal articles, compared to which the rate of forced retractions is negligible. The rates of correction vary widely across subject areas and journals. Biomedical fields have the highest rates of self-correction while multidisciplinary journals have by far the highest correction rates and include some of the most widely read publications, which should remove any perceived stigma associated with questioning results and reporting errors. Other editorial boards should be encouraged to emulate these journals by establishing sections for reader commentary and policies for publishing corrections so as to encourage a tradition of vigorous scientific debate and self-correction.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.