This Article From Issue

May-June 2022

Volume 110, Number 3

Page 137

Anabel Ford first encountered the ancient Maya settlement of El Pilar, which straddles the border between Guatemala and Belize, in 1983, and she has been working at the site ever since. El Pilar was filled with plazas, temples, and palaces, which were built from 800 BC to 1000 AD. Ford is a proponent of what she calls “Archaeology Under the Canopy,” excavating the site while engaging local Indigenous people, many of whom are Maya descendants, for their knowledge of what materials would have been used to build houses, and what plants would thrive there. Indeed, in addition to the extant structures, Ford has focused on preserving the Maya’s carefully tailored forest ecology practices that supplied them with food and building materials. El Pilar is now designated as an archaeological reserve and a cultural monument, and Ford has helped to found the El Pilar forest garden network to preserve Indigenous knowledge of Maya land management. As a doctoral student, Ford received a Sigma Xi GIAR grant that she used to study the volcanic ash composition of Maya pottery. Ford spoke about her developing understanding of this Maya site with American Scientist editor in chief Fenella Saunders. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Anabel Ford/Mesoamerican Research Center, UCSB

What have you uncovered about the source of volcanic ash in Maya pottery?

I did not discover volcanic ash in Maya pottery, but I discovered what it meant to geologists. The Maya lowlands is hundreds of kilometers away from fresh volcanic sources. Ancient Maya ash-tempered pottery was first recognized in 1937, but ash temper was simply used as a chronological marker with no reflection on the source. The topic resurfaced in the 1980s with my work and the work of others. When I worked with volcanologists and did petrography on thin sections of the sherds, the volcanologists were just floored, because to them it looked like the sherds had captured a contemporary airfall of volcanic ash. It looked like fresh ash embedded in the pottery, and tons of it. There was no evidence of abrasion, no indication of human manipulation, and the sorting and size were consistent with wind distribution. I had to convince them even that some of my samples were not mud, that it was really pottery, it had been fired.

I thought we were going to solve all the problems of the Maya by finding that they collected the ash because it fell into their hands during the Late Classic Period (600–900 AD), and the eruptions also brought fertilizing volcanic minerals into the lowlands, so it explained the rise of the Maya. And then when that ashfall stopped somehow, we didn’t know how that would have happened either, but that it would also explain the collapse. So we wanted to explain it in one volcanic swoop. We did a whole bunch of studies that we thought were going to solve these problems, but all it did was make it more difficult to sort out, because nothing was obvious.

We tested four sherds, and the constellation of elements that emerged made it look like the volcanic ash in each had different sources. Although the volcanic glass had gone through temperatures and pressures unheard of in open pottery firing, still, when we conducted experimental firings with local raw clay matrices and ash samples from one of the closest volcanoes, Ilopango, at four temperatures, we found significant changes in the volcanic glass with firing. The size of the ash particles also made a difference.

I then got in contact with a researcher who looks at zircons, and he thought for sure that this was going to be the solving of all of it. Zircons are some of the most stable and long-lived elements on Earth, and zircons crystallize in preeruptive magma associated with each volcanic eruption. The researcher had identified and dated zircons from the Ilopango eruption that we had considered our prime candidate for the Late Classic pottery temper. But our archeological zircons did not match the Ilopango zircons. Ilopango’s zircons dated around 10,000 years. The pottery’s zircons came up with ages that are greater than 30 million years! So the Maya were not using Ilopango ash.

The project keeps going on. There will be no simple answer to the presence of volcanic ash in the Maya lowlands. But right now, my colleagues in Heidelberg have a whole bunch of my sherds, and they’re going to try to find more evidence.

How did you first encounter your main study site, known as El Pilar?

I was doing a survey that was looking at settlement and environment in the Belize River valley. The site is 10 kilometers from the river, and the assumption using the Western view was that water and the river were very important both for drinking and for transport. But the river length is about 350 kilometers and the same distance on land is about 100 kilometers, probably a three-day walk. Paddling 350 kilometers is a lot harder and going downriver probably is okay, but in the wet season it would be treacherous, and in the dry season, there would be a number of portages. So I’ve never seen the waterways as a dependable component of transport in Mesoamerican life. However, the work that had been done had only been in the Belize valley near the river. So I did transects going out into the upland areas, and as I was doing it, I asked what people knew, and local people said that there was a big site. I went up and yes indeed, there was a big site. I had never mapped anything that big.

How big was El Pilar?

I estimate that there were about 300 to 400 people per square kilometer in the city. And that makes the population of the city of El Pilar, something like 4,000 people. A traditional Mayanist will count each structure as a house. So if at Tikal we have 200 structures per square kilometer, that means 1,000 people per square kilometer. But in fact, I don’t consider all of those structures to be houses; I consider a primary residential unit of structures. One structure is the kitchen, and one’s going to be the place where they live. If they use fire, they never have it inside, it’s really fire insurance, but you could not have a home without having the kitchen. So I actually define primary and secondary domestic architecture, and I only estimate population based on primary residential units with five people. I look at things very practically and how they might actually have thrived.

What assumptions about the Maya have you had to counter in your research?

I think that my education implied that the people who became the Maya civilization somehow appeared in the lowlands already as agriculturalists. And in fact, I would say there was almost a feeling that there was no precedent, but when you look at human occupation, why wouldn’t that area have been occupied? People are everywhere. When you look at how much the tropical forest offers, you don’t have to do much, you can pick the fruit off the trees and there are animals all over.

There was also another idea that forest dwellers could not be hunter- gatherers, which I never quite understood. The presumption was that hunters had to be out there in the bush, chasing big game. There isn’t big game like that in the forest, but in the teeming forest, every habitat has something. I actually went out with a hunter, and he strung up a hammock and took a snooze! I said, “Are we hunting?” And he was a sort of mischievous fellow, so he says, “Did you come with me because I’m a hunter or not?” So I said, “Okay, okay!” Soon enough, a little agouti comes up and he hammers it with the butt end of his shotgun, and there’s meat. He showed me that he put his hammock over the place where the animal was going to come, he was reading the signs of where it lived. I thought, well, you don’t have to run after things, they come to you, if you’re informed.

The Western world also still wants to find canals and terraces, anything that’s hard-surface land use, to show intensive effort. They can’t imagine intensive agriculture that doesn’t leave any evidence. Yet the biggest center of the classic Maya period, Tikal, has no evidence of terraces or canals.

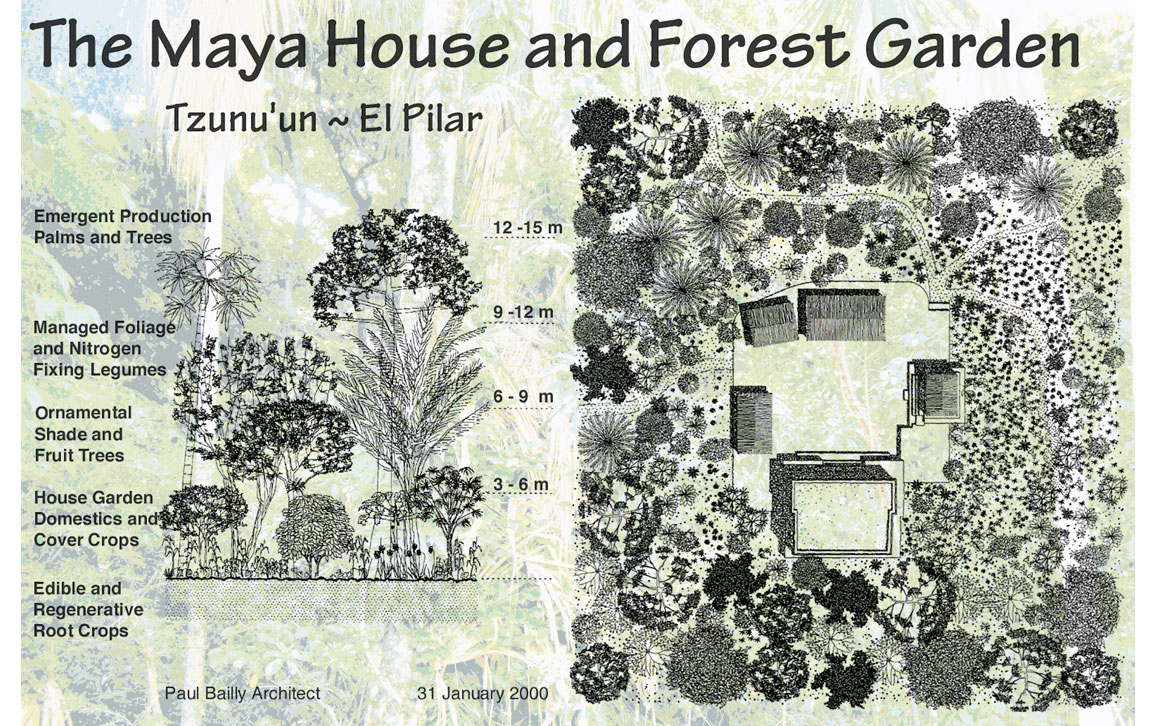

What have you documented about Maya cultivation within the forest?

Studies show that the forest today was shaped by practices developed by the Maya millennia ago, using an Indigenous production system called the Milpa Cycle that continues to be practiced by forest gardeners today. Rocky soils are considered undesirable in European cultivation systems centered on the plow, but Maya did not use plows. It was inconceivable to observers that the Maya cultivation system could support large populations and complex societies without destroying the shallow tropical soils. Because components of the Milpa cycle include slash-and-burn fields, popular perception sees only shifting agriculture and discounts the majority of the landscape as abandoned.

“The Western world still wants to find canals and terraces, anything that’s hard-surface land use, to show intensive effort. They can’t imagine intensive agriculture that doesn’t leave any evidence.”

Milpas are mixed-plot lots. It is not unusual to find more than 30 different crops in one field, out of more than 100 possibilities. The Milpa cycle averages 20 years, starting with fields of traditional agricultural crops for about four years, progressing through a sequence of products obtained from selected secondary growth, and completing with a closed canopy forest over the original cleared area, which is ready to repeat the cycle again. Forest gardening strategies have also developed to be responsive to climate change, because they maintain land cover that enhances biodiversity, conserves water, and moderates temperatures. Master forest gardeners say there is no forest without the fields, and there are no fields without the forest.

What have you learned about land management from the Indigenous people of the region?

In 1995 I got a grant from the Ford Foundation and part of it was to create a way for traditional people to get engaged with El Pilar. I did it by excavating a Maya house, and I wanted to imagine a house in a forest garden. So I brought in forest gardeners to ask what could we do up at this Maya site? I wanted to have cacao, for example, but they said, no you can’t have cacao here. It wouldn’t work because that area has basic soil with lots of limestone and apparently cacao doesn’t like that. It wants to have a deep sort of clay soil. So there’s a lot to learn. Working with them was really instructive.

I planted trees at my field base where I have a house, and I have a mahogany tree that is quite large now, it’s 15 or 16 years old. And I said, oh, it’s big enough to be a good post. And, oh, they laughed forever on that one. They said you never would make that a post because it would just deteriorate. It would not be something you could put in or near the ground. It would be good for other parts.

I was going up to an area where I heard that there was running water, which is very rare in this place. Mostly, you don’t have surface water. And so this forest gardener knew something about that, and so he took me to it and I said, “How did you find it?” I discovered that it was because of a damselfly. I would say, “Oh, a bug, I don’t want it in my eyes,” but he would say, “That’s water.” So all those kinds of experiences add up to say that there’s skilled observation, things that I don’t see. I mean, I know what a stoplight is, but I don’t know that a damselfly means water.

Anabel Ford/Mesoamerican Research Center, UCSB

There are two rainy seasons in the Maya lowlands. One is the hurricane, and that’s governed by the InterTropical Convergence Zone. And then there’s the North Atlantic Oscillation in which the weather comes down from the southeast United States, and that’s cold as well as wet. They are different time periods and the distribution depends on when rain comes. If all the water came in October, that would destroy a crop, but if there was very little rain but it came scheduled perfectly when needed, the crops would be fine. It’s a monthly and almost daily kind of thing that has to be dealt with. And it’s not just one season, it’s two seasons of rain. And that’s something I’ve learned from the forest gardeners.

They have skills that are undervalued because they are not quantitative; you can’t measure them like linear kilometers of canals or meters of terraces. But it is investment. When I write papers, I have the forest gardeners read them for me and they’ll make critiques. The most recent paper I wrote, my forest gardener colleague Alfonso read the section on the milpa, because I know that he’ll find something wrong. But he said he didn’t have a quarrel with it, so I was quite happy.

How have you used LIDAR to map and document the El Pilar site?

LIDAR is no magic wand, but it provides the entire topography. If I were to do a topographic map with the scale of LIDAR, it would take me years. I’m doing a project with a geospatial engineer this season; I’ve surveyed 14 square kilometers and we have targeted what I call go-to points in that area to compare with the LIDAR mapping. We’ve discovered things and we have rejected things from LIDAR. I feel like when I go out in the field, our go-to points are probably in the 80-percent range of accuracy, but we find things that you wouldn’t be able to see with LIDAR. I’m interested in land use, in finding out what proportion of the house sites we’re capturing versus what the LIDAR can see. LIDAR is terrific, but if we’re going to be sure we know something, we have to compare what we see on LIDAR with the boots on the ground. And then we could say how great it really is. With LIDAR, you know where the swamps and the uplands are, you can start seeing where you could put emphasis and where you don’t have to. I believe in sharing these data; we have created a Maya forest atlas online with our data, and we could make so much more progress if all the LIDAR data were made public.

Does preservation of the site sometimes conflict with Indigenous practices?

The government approach to managing the monuments, the top-down approach, is the standard. For example, at the site, I envision Archeology Under the Canopy, and that means forest gardeners teaching people how to manage things. Yet park rangers are raking, clearing, taking plants away, sweeping away all the cover, which is going to cause erosion. Maya forest gardens invite plants, take recommendations from nature, and give something we can learn from, such as keeping moisture, inhibiting erosion, building biodiversity. Beautiful ferns they remove would not have hurt the monuments. So right now we’re starting the dry season, and everything looks dry even before the dry season. The rangers are responding to what they see as clean, and we are working to build a strategy that can bring the forest gardeners to the table. There is plenty there to do, I can tell you.

Do people see the forest gardening approach as a way to reclaim their cultural heritage?

After this COVID event, people want more sovereignty, want to be able to eat something that they know where it’s from, and even have something to eat without having to buy it. So there’s more interest in the forest garden now than there was before.

We just signed a memorandum of understanding with the Belize National Institute of Culture and History to create a permanent exhibit on El Pilar and the forest gardens, which would link to the new Belizean education program. I think it’s going to affect how people perceive their own gardens and their own investment in plants. So many things that are part of that Maya forest garden approach have applications well beyond the Maya area. For instance, we have to conserve water, we have to consider biodiversity, we have to consider temperature.

“We have been working toward creating a binational peace park at El Pilar.”

We have also been working toward creating a binational peace park at El Pilar. The space is bounded by both Belize and Guatemala. It’s contiguous, it’s well recognized in both countries, and the management planning themes are equal in both countries, so it could happen. I mean, maybe not in my lifetime, but my goodness, everyone said you couldn’t have a binational park. In 2019, both countries had voted in favor of a referendum to bring their long-standing territorial dispute to the International Court of Justice. And that’s moving along. And the current ambassador from Belize to Guatemala is someone I’ve known from agriculture. He’s very interested in the forest garden concept. And so maybe enough seeds are planted and maybe something can happen. I’m a cheerful pessimist, but that’s what I’d really like to see.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.