Paleogenomic Puzzles

By Catherine Clabby

DNA sequences of extinct hominins could rewrite human ancestry

DNA sequences of extinct hominins could rewrite human ancestry

DOI: 10.1511/2011.90.210

A research team led by Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology dropped two bombshells on the field of paleoanthropology last year. But how the new data may rewrite our understanding of human ancestry remains uncertain today.

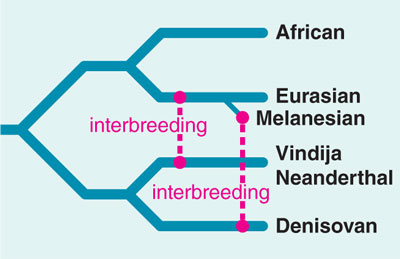

After sequencing multiple genomes of Neanderthals, our extinct but closest known relatives, the researchers concluded that Homo sapiens early to reach Eurasia from Africa had interbred with Neanderthals. The evidence: Non-Africans living today share distinctive DNA sequence with Neanderthals, who lived in Eurasia from 200,000 to 28,000 years ago, they say.

Illustration by Barbara Aulicino.

Later, they identified a new group of extinct hominins—called Denisovans—using DNA retrieved from a young female’s finger bone recovered in Denisova Cave in Siberia. Denisovans, they say, also interbred with Homo sapiens, but only a small group of modern people—those living today in Papua New Guinea—are known to retain evidence of that ancestry in their genomes.

“The situation is fantastic and a bit of a first in genetics,” says Nick Patterson, a computational biologist at the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts who is closely involved in the research. “The normal thing is that you have a species, maybe even an ancient species. But the physical characteristics are very well known. Then you learn about the genetics.”

Not all paleoanthropologists are convinced by these findings. Richard Potts, director of the human origins program at the Smithsonian Institution, says the Neanderthal-human interbreeding evidence was highly convincing, in isolation. But when the Denisovan argument emerged later, he wondered if the scientists had found something other than what they concluded. He suspects the sampled Neanderthal, Denisovan and Homo sapiens genomes could retain DNA sequences from an earlier hominin, possibly Homo heidelbergensis.

Chart adapted by Barbara Aulicino from Pääbo et al. 2010. Nature

“What we may be seeing instead is the parceling and division of DNA from a last common ancestor. That could have a different echo in different groups of modern humans,” Potts says.

Pääbo’s team is trying to strengthen evidence for their findings. Patterson, for one, is working on what he calls a genetic recombination clock to better estimate when Homo sapiens and Neanderthals might have interbred. Pääbo says they are also analyzing more bones from the Denisova Cave and from other locations in the hope that they will yield more DNA. “It would be interesting to see how widespread Denisovans were in the past,” he says.

Pääbo, director of evolutionary genetics at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig, hopes that DNA can also be retrieved from Homo sapiens who reached Eurasia during our species’ first sizable dispersal from Africa about 80,000 years ago. Potts of the Smithsonian sees promise in the same line of research. He is hopeful that DNA someday can be recovered specifically from the Qafzeh fossils from Israel, which are about 130,000 years old, and from the Liujiang fossil from China, which is at least 68,000 years old. Sequences from H. heidelbergensis, he says, could be awfully interesting too.

“Getting genes out of fossil bone is terrific. It opens new possibilities,” he says.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.