This Article From Issue

November-December 2008

Volume 96, Number 6

Page 516

DOI: 10.1511/2008.75.516

CONVERSATIONS WITH WENDELL BERRY. Edited by Morris Allen Grubbs. xx + 218 pp. University Press of Mississippi, 2007. Paper, $20.

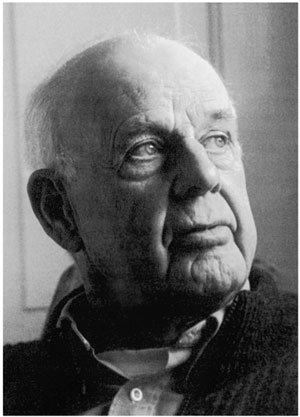

In a time when so many of us are concerned about humanity's effect on the environment, or at least claim to be, it is fascinating and instructive to read Conversations with Wendell Berry, a collection of 17 interviews with the well-known farmer/conservationist and writer/teacher. Berry has long been an exemplary caretaker of land and community. This book allows us to witness his early wisdom and insights.

The interviews collected here span the years from 1973 to 2006; reading them, I was taken with the prescience of Berry's vision and also drawn to the consistency of his hopes and concerns for the health of small local communities, both human and natural, which are to him integral and necessary for global sustainability. As the book reveals, little has been accomplished in the past three decades, and those local communities are as much at risk today as they were 30 years ago. A number of current concerns—the merits and methods of organic farming, the prevention of soil erosion, the importance of minimizing our carbon footprint, the advantages of developing a local economy that is independent of global corporations—were addressed by Berry as long ago as 1973, when Bruce Williamson interviewed him for Mother Earth News.

Berry asserted in that interview that "our culture today is mainly embarrassed about country things." Had that not been the case, the United States long ago might have asked the questions about land and place that he suggests we still need to consider. In a 1993 interview, he expressed them this way: "What is the nature of this place? And then: What will nature permit me to do here?" Consideration of these questions might have led us to recognize the inherent economic connections between country and city, between what is grown and what we eat, between what natural resources are available and how they are consumed—and to accept and act on the responsibilities that those connections imply.

Instead, this wisdom has largely been ignored in the United States. It may be, as Jason Epstein asserted in the May 15, 2008, issue of the New York Review of Books (in response to a letter from Berry), that much of America is "too poor and too distracted to take advantage" of small-scale farming. But a more plausible explanation might be that skewed priorities get in the way. As Berry observed back in 1973, "our society is interested in growth and production." And as he asserted much more recently, in 2006,

We've been taught to think that the only economic virtue is competitiveness. This is a faith: I'll get into it for all I'm worth, seeking the maximum advantage for myself.

To think that seeking such advantage "will result in good," Berry says, is "a preposterous notion."

In another, previously unpublished, 2006 interview, Berry reminds us that

the single goal of the industrial economy, from the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, has been the highest possible margin of profit. That is to say that its single motive has been greed. The economy justifies itself as a sequence of innovations that it calls "progress." But it is progress for the sake of the biggest possible profit. Industrialism is the most effective system ever devised for the concentration of wealth and power. Its most characteristic "progress" has been the increasing ability to concentrate wealth and power into fewer and fewer hands.

This view of society is antithetical to the "cooperative economy" that Berry has sought to depict in his writing and to manifest in his farming and in his relation to his own community of Port William, Kentucky.

Of course, Berry's insistence on the integrity and significance of the small locality and the family-run farms that are its core was a radical idea in 1973. Also radical was "Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front," a sequence of poems he published that year. That work served both as a celebration of human connectedness to nature and as an accusation and directive for a society that lagged in its response to environmental and communal concerns.

It is not surprising, then, that in a 1990 interview, Berry was already warning of the insidiousness and danger of our reliance on plastics. "When petroleum becomes too expensive to make plastic, then people will have to do something," he said. It is also telling that as early as 1973 Berry was advocating using composted human waste as fertilizer (a subject that has recently received mainstream media attention, most notably in an article by Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow in the Boston Globe).

Yet Berry acknowledges that society's ideas are slow to evolve. What is so satisfying about this collection is that we are reminded of how hard and consistently he has worked, over the course of many years, to bring about his vision. We are also reminded of the rare synthesis he has achieved: In addition to writing about the environment, he has developed a sustained, sustainable and—what is most important—an ethical relationship to the land, as outlined by Aldo Leopold in 1949 in A Sand County Almanac. Berry realizes that the best way we can know the natural world is through the imagination and through our immediate engagement with the land—an engagement that presupposes hard work, manual labor and the acknowledgment that "we live in, and from, the land economy."

Within the context of sustainable communities, Berry's thoughts are wide-ranging. These interviews provide a compelling venue for him to speak about writing, art, culture, religion, education, poverty, language, history and time. The wisdom revealed in this book is the result of Berry's decision to abide in the world, to exert himself daily in the effort to comprehend and to engage with both the human and the natural landscape. And although his work is primarily local, the effects of his inquiry are far-reaching. This book should be required reading for all writers, scientists, environmentalists, politicians and educators—indeed, anyone who would see American society healthy once again.

Christine Casson is Scholar and Writer in Residence at Emerson College in Boston. She is the author of After the First World, a book of poems (Star Cloud Press, 2008). She has published critical essays on the work of Leslie Marmon Silko and the poetry and environmental essays of Linda Hogan and is currently writing a book of nonfiction that explores the relationship between trauma and memory.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.