This Article From Issue

September-October 2008

Volume 96, Number 5

Page 426

DOI: 10.1511/2008.74.426

A SACRED LANDSCAPE: The Search for Ancient Peru. Hugh Thomson. xxii + 330 pp. The Overlook Press, 2006; first published in the United States in 2007. $27.95.

The great civilizations of the New World, especially those of South America, have yet to capture the imagination of the North American and European publics. How many of us know, for example, about the Moche culture's Lord of Sipán, whose burial accompaniments rival those of the far more famous Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun? And how many of us are aware of the extraordinary stone craft of the Inca—perhaps best represented at Sacsayhuamán in Cuzco, the capital of their empire—which is fully equal to (and some would say surpasses) that of any Old World civilization? Hugh Thomson, a British writer and self-described explorer, has set himself the task of redressing this situation through his thoughtful writings covering 5,000 years of Andean prehistory.

Thomson joins a long and illustrious list of explorers, scholars and writers intent on bringing the Andean world into clearer focus. In 1877, Ephraim George Squier, who first gained fame by documenting the ancient mounds of the eastern United States, published Peru: Incidents of Travel and Exploration in the Land of the Incas, shamelessly copying the title of John Lloyd Stephens's highly successful 1841 book on his travels in the Maya world, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan. And early in the 20th century, Adolph Bandelier wrote a volume describing his travels and research in the Lake Titicaca basin.

The most famous of these early writers and scholars, however, is Hiram Bingham, who discovered (some say rediscovered) the famous late-period Inca ruins at Machu Picchu in 1911. He not only described the site in some detail for an academic audience but also wrote a number of books for popular consumption, one of which (Lost City of the Incas) became a best seller in 1948. Bingham figures prominently in Thomson's latest book, A Sacred Landscape, both as inspiration and as foil.

Three themes run through Thomson's exploration of the Andean past: the lure of the lost city, a desire to explain what appears to be long-term continuity in the form and content of Andean cultures, and the notion that the Andean world is perhaps best characterized as a sacred landscape. Each of these themes has been the focus of archaeological research in the Andes for decades. What Thomson has done is to offer a panorama, linking them through his experiences of more than 25 years of walking through the Andes and writing about Andean peoples and their past. His is also a personal exploration, an attempt to make sense of this long relationship in terms that might make sense to others who have yet to get to know, and possibly love, the Andean world.

The book begins and ends with the search for a lost city. As early as colonial times and the myth of El Dorado, the city of gold, the Andes beckoned to fortune hunters, explorers and the restless. Because of their remoteness and difficult terrain, the eastern flanks of the Andes as they descend into the Amazon basin have long been the venue for such projects, and 20th-century history is replete with putative discoveries of lost cities, some of which turn out not to have been so lost after all.

Thomson's focus is on Llactapata, which is perched on a long, narrow ridge within view of—and a day's journey from—Machu Picchu. Bingham apparently discovered one part of the site in 1912 but did not investigate it; Thomson looked for that spot in 1982 and seems to have ended up mistaking a different part of the site for Bingham's find. Johan Reinhard appears to have stumbled on yet another sector of the site in 1985. In 2003 Thomson returned to the area with a research team, which located all three of those sectors, found a fourth one as well, and initiated limited research.

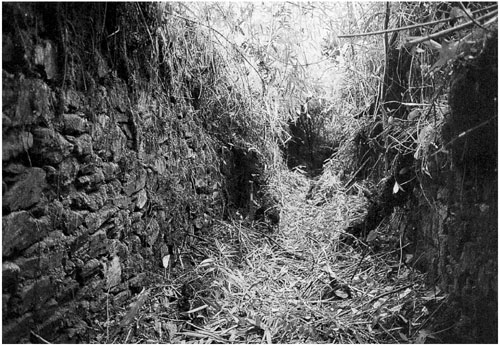

From A Sacred Landscape.

Structures at the site are obviously Inca and reflect a careful, organic placement on the landscape. One feature, however, perplexed the team: a long, narrow passageway with no hallmarks of typical Inca structures. Subsequent analysis showed that this sunken corridor was positioned so that the rising of the Pleiades in early June as well as the summer solstice could be observed from within it. Both events figured prominently in the Inca ritual calendar as markers of the agricultural cycle. Questions raised by this nexus of landscape, architecture and religion set Thomson on his quest to seek its origins as well as to explain its apparent persistence over time.

His book, which reads like a good travelogue, is full of anecdotes, humor and insight into the lives of the people he meets along the way. Many of those encounters are well lubricated with chicha (a homemade fermented drink, often made from maize) from the Peruvian coast or the harder stuff of the expat bars of Cuzco. Along with a variety of interesting companions, each with his or her own story, he visits the iconic societies of the Andean past. Caral, which is dated roughly between 3000 b.c. and 2000 b.c., is part of a complex of early sites along the coast that have monumental and other civic architecture. Some people (including Thomson) consider Caral to be the foundation of Andean civilization; Chavín, which appeared around 800 b.c., is the former candidate for that honor. Moche culture, with its fascinating iconography of sex, death and human sacrifice, appeared around a.d. 100, and the Nasca civilization, with its famous geoglyphs (lines on the desert floor depicting birds, animals and a variety of geometric figures) began about a century later. Other places visited by Thomson include the so-called Sacred Valley near Cuzco; Huari (aka Wari), a state that arose in the highlands near Ayacucho around a.d. 600; and the Island of the Sun at Lake Titicaca, which was used both by Tiwanaku peoples and by the Inca.

Thomson's descriptions of the archaeology of each site are reasonably accurate, but he often veers into dubious interpretations, one of the most prominent being his strong belief that Andean religion from the very beginning was directed at controlling the deities who themselves controlled the unpredictable climate of the region. Although there is little doubt that rituals for agricultural fertility were prominent in most of these societies, archaeologists have also discovered other motivations for Andean religious belief and practice. For instance, many archaeologists, such as Richard L. Burger of Yale, believe that the religious activity manifest at Chavín is suggestive of a cult that spread rapidly across the Andean highlands and may have been more concerned with politics and foundations of leadership than with control of deities.

But perhaps the greatest problem with the book is the very intellectual foundation of Thomson's quest. In Peru the term lo Andino, which translates roughly into "the Andean way," is used to characterize what is seen as a set of customs, patterns of land use, religious beliefs and traditions that are thought to be unique to the Andes and particularly adaptive to the harsh environment there. Although the phrase has the advantage of emphasizing commonalities in these adaptations, it also has the more negative effect of creating an overly reductive, unchanging view of both ancient and modern peoples, effectively removing them from history and depriving them of active agency in the shaping of their cultures.

Modern ethnographic research shows that lo Andino is remarkably flexible, and that what is deemed traditional today may not be so tomorrow. In effect, lo Andino is a sort of reverse-engineering approach to explaining the past. One finds something that merits explanation—the existence of a sacred landscape, say—and then systematically reviews the archaeological evidence that such landscapes existed in earlier cultures. And of course anyone looking for such evidence usually finds it.

From A Sacred Landscape.

But a key question remains: Is there necessarily a causal link between past and present? Did a 5,000-year-old sacred landscape like the one posited by Thomson for Caral on the Peruvian coast actually lay the foundation for the way the Incas viewed their landscape? If so, just how did this happen? What sorts of models of cultural transmission could possibly support such an assertion? Sadly, lo Andino is an assumption, and not a demonstration, of continuity.

It may seem less than generous to criticize Thomson for not having written a more scholarly book, for that was not his goal. But it is fair to caution an interested reader that, although it's fine to enjoy the journey, one should be very skeptical indeed of Thomson's romantic and heartfelt but ultimately implausible rendering of the Andean past.

Mark Aldenderfer is professor of anthropology at the University of Arizona in Tucson. His interests include the archaeology of cultural and biological adaptation to life at high altitude. He has conducted research on the world’s three high plateaus, in Ethiopia, Peru and Tibet, and is the author of Montane Foragers: Asana and the South-Central Andean Archaic (University of Iowa Press, 1998).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.