A Light Switch on Cells

By Fenella Saunders

A chemical makes neurons turn on and off with light beams

A chemical makes neurons turn on and off with light beams

DOI: 10.1511/2008.74.376

As visual creatures, we have a long-standing convention to associate illumination with understanding—for example, we say that "a light dawned" when we finally get a concept. But the cells with which we actually do our thinking are always in darkness and usually have no need for luminance. However, some kind of photochemical control is actually very useful for scientists who are trying to figure out exactly how neurons work and what systems they influence. A light beam is non-invasive, precise and relatively harmless to cells, causing little disruption to their normal processes.

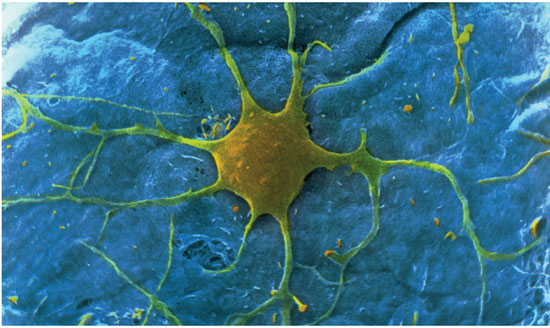

PHOTOTAKE Inc./Alamy

There are ways to make neurons photoreactive, but they involve the introduction and expression of foreign genes, which can be slow or give non-uniform results. Such methods also don't work in some systems and can disrupt others, sometimes inhibiting the very functions that are the goal of the endeavor. A group of molecular biologists and chemists at the University of California, Berkeley, led by Richard H. Kramer, have now created a photosensitive compound that attaches to cells by purely chemical means, eliminating the need for genetic engineering. On top of that, their mechanism may also be useful in working around certain types of blindness.

Kramer and his colleagues focused on potassium channels, small pores in cellular membranes that control the excitability of neurons. When sending a signal, a neuron releases ions into the synapse, or gap between connected nerve cells, and these ions are then picked up by the potassium channels on the receiving cell, signaling it to fire. Thus, gaining control of the potassium channel confers the ability to decide whether or not a neuron will work.

As the researchers report in the April 1 issue of the journal Nature Methods, they created a molecule dubbed a photoswitchable affinity label, consisting of a long tether with a protein-binding group on one end and an electrophilic group at the other. The electrophilic group anchors to an amino acid on the outside edge of the potassium channel, whereas the protein-binding group acts like a plug on the channel opening. "When this blocker is in place, the potassium physically cannot get through," Kramer says. To attach the label, the researchers simply bathe cells in a solution containing the molecule.

The tether part of the label is a molecule called azobenzene, which is a photoisomer, meaning that its physical shape, but not its chemical composition, changes when it is exposed to light. It is normally in its long form, and it will also quickly restore itself to this shape when it is exposed to long-wavelength light—around 500 nanometers, or in the blue-green range. However, when the molecule is hit with a shorter wavelength—around 380 nanometers, or the violet range—it bends. "The light adds energy to the system that breaks a double bond and reforms the molecule in a different configuration with a kink in it," explains Kramer.

So, in a neuron with such a label attached, when hit with violet light, the tether bends, the plug pops out of the potassium channel, and the nerve cell can fire. Shine a blue-green light on it and the tether will stretch back out, again blocking the potassium channel and silencing the cell. Once toggled on or off in this fashion, the label will stay put for extended periods, so it does not need to be continuously illuminated. The switching can be done repeatedly without damage to the label or the cell, giving the neuron persistent sensitivity to light. The exact response time depends on the intensity of the beam, but it is in the range of hundreds of milliseconds. "The greater the light intensity, the greater the probability that one of these molecules is going to get hit by a photon of the right wavelength," Kramer says.

Kramer and his colleagues tested the mechanism in single cells and in slices of brain tissue, demonstrating that the light will penetrate to cells below the surface. "There are people developing microendoscopy, which uses light from an optical fiber to image very deep structures in the brain, down to single-cell resolution," Kramer says. "We might be able to use something like that to regulate neurons deep in the brain."

The researchers showed that they could control the signaling in neurons that regulate the heartbeat of leeches, cells in which gene expression has been difficult to achieve. Such results indicate that the labels could also be used to influence endocrine functions or vascular contraction. The group is now working on labels that may control other signaling channels in cells.

But Kramer is most excited about the possibility of using the labels to help restore sight. "There are disorders where kids go blind over time because they lose their rods and cones progressively over the first decade of life, and once they're gone there's no bringing them back, so far. As it stands now the photoreceptors are absolutely required for vision," he says. "So the long-term hope is that something like the compounds we've developed might be able to restore sight using cells that aren't normally light sensitive." It could be possible to substitute for the retina's rods and cones with nerve cells downstream in the vision process that do not normally pick up photons, but could be induced to do so through this labeling process. Kramer and his group have done tests on whole, damaged retinas from mice that model human degenerative vision diseases, and found that these photoblind cells can be made to fire when labels are added to them.

The next step will be to see if treating cells in a blind animal causes behavior changes, indicating that the nerve signals are being successfully translated into sight. If the method ever does end up being used successfully in humans, it may require some way to continuously deliver the labels. The proteins on the surface of potassium channels that bind the labels are turned over on a regular basis, so photochemical control may only last so long without renewal. "We do know it remains very stably associated with the channel for up to 24 hours, and the neurons in which they find themselves stay sensitive to light," Kramer says. "It's not clear if the molecule is being broken down or if the protein target is getting turned over, but the duration may be quite different depending on what tissue or what part of the cell you're looking at. Ion channels turn over rapidly in the cell body but maybe not so much so in the axons."

Still, the biggest advantage of using these labels in the retina, Kramer notes, is that it's an area of the body where there's no difficulty getting photons to the tissue. "Light gets to the retina, so it's the one part of the nervous system that's naturally exposed to light."—Fenella Saunders

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.