DIY Science

By David Schneider, Kristen Greenaway, Dane Summers

Eccentric Cubicle · Stomp Rockets · Amazing Rubber Band Cars

Eccentric Cubicle · Stomp Rockets · Amazing Rubber Band Cars

DOI: 10.1511/2008.73.347

ECCENTRIC CUBICLE. Kaden Harris. O'Reilly, $29.99.

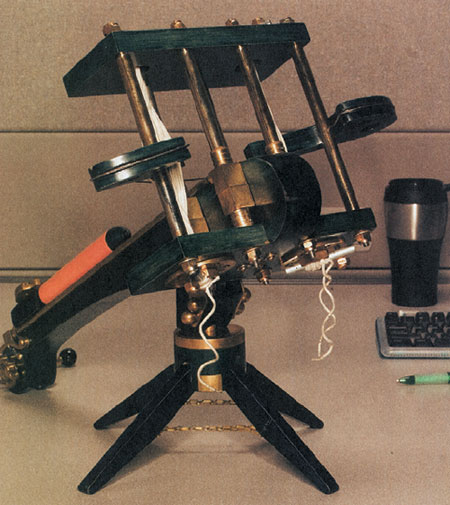

You may be forced to earn your living in a dreary office cubicle, but never fear: With Kaden Harris's Eccentric Cubicle, you can add zest to your boxed life. Tired of sending e-mail messages to your coworkers? Loft written notes to them using a miniature, homemade "ballista" (right), an ancient engine of war that Harris describes as a sort of Greco-Roman cruise missile. Built with generous amounts of brass and hardwood, the do-it-yourself projects in this book are said to resemble "antiques from a parallel universe"—and color photos of the steampunkish contraptions confirm that appraisal.

From Eccentric Cubicle.

The book prominently advertises on its cover a connection with O'Reilly's Make magazine, which caters to people who like to build geeky things using mostly salvaged junk. Harris offers valuable pointers on this art and shows great appreciation for the history of science and technology. His irreverent attitude and sense of humor are apparent from the get-go. And his quirky creativity is fun to read about. But if you plan to build one of these cubicle accessories—be it the Haze-o-matic 3000 fog machine or the Gysin brain-wave stimulator—be aware you are unlikely to be able to assemble the same starting materials that Harris chanced upon in junkyards and at swap meets.

A more troubling flaw is that the book fails to promote good technical skills. The reader is not shown how to craft devices but how to kludge them together. Worse, some of the maneuvers described seem ill-advised—say, using your drill press as a lathe. The book may be a reasonable place for a young tinkerer to start, but it's certainly not where you'd want her instruction on craftsmanship to end.—David Schneider

STOMP ROCKETS, CATAPULTS, AND KALEIDOSCOPES: 30+ Amazing Science Projects You Can Build for LESS THAN $1. Curt Gabrielson. Chicago Review Press, $16.95, ages 9 and up.

What a deal: 30 science projects, each of which costs less than a dollar to build! Curt Gabrielson, director of the Watsonville Environmental Science Workshop in California, says that in fact, most of the toys in his captivating hands-on book, Stomp Rockets, Catapults, and Kaleidoscopes, can be cobbled together for about 75 cents. "If you can't squeeze that out of your parents," he adds, "you need to work on your technique."

All of the projects require basic tools found in most homes, such as a hand drill, screwdrivers and pliers. Good scavenging skills should turn up most of the other materials needed.

One of the book's most appealing projects is the xylophone and marimba. In the process of building them, young people will discover that sound comes from vibrations, that the frequency (or pitch) depends on the rapidity of those vibrations, and that the volume depends on their amplitude. And the homemade musical instruments will be fun to play.

The tornado, another exciting project, uses one part that will likely require a trip to a hobby store: a small motor. Everything else can probably be found around the house. The motor drives an impeller inside a bottle filled with water, which should result in spectacular visual effect—particularly when food coloring, glitter and bits of Styrofoam are added. Conversations can be sparked about what starts the rotation within the bottle and how rotation comes about in real tornados, hurricanes and whirlpools.

Gabrielson's advice to adults is excellent: Don't take over the project (grown-ups are the assistants), don't demand perfection, and let kids make mistakes!—Kristen Greenaway

AMAZING RUBBER BAND CARS: Easy-to-Build Wind-Up Racers, Models, and Toys. Mike Rigsby. Chicago Review Press, $12.95, ages 9 and up.

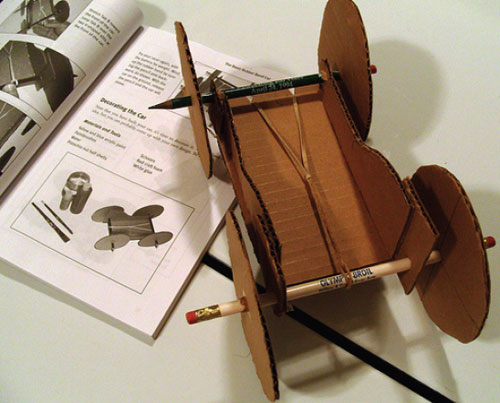

Amazing Rubber Band Cars introduces parents and children to the art of engineering—or, as author Mike Rigsby puts it, "the application of scientific principles (knowledge) to practical things that people use." The book's designs for cardboard cars powered by rubber bands fit this description perfectly. The writing style is accessible, and each step is liberally illustrated.

After reading the book, I was skeptical that I could sustain the interest of a child through the multistep building process that even the simplest model would require. But I changed my mind once I had built the first project, "The Basic Rubber Band Car." It took just a few minutes to cut out all the parts and glue together the car's body. I felt a sense of accomplishment as great as if I had just built a log cabin from felled trees. Next I glued pencil axles to cardboard wheels and attached a rubber band. When the glue was dry, it was ready to roll, and I took the photo shown at right. Children already experienced with building things will probably be able to construct these cars with no assistance; others will enjoy making them with their parents.

On its test run, my little car was a bit slow. But a couple of sections further into the book, I found out that I could increase its speed by using aluminum-foil bearings to reduce friction. In the "Distance Car" section, I learned how to go faster still by adding a high gear. Other projects include a locomotive; "Oscar," a rolling clown with a bobbing head; a two-wheeler that uses fishing weights to wind the rubber bands; and finally, a human-scaled cardboard car (yes, rubber-band powered!). Truly amazing.—Dane Summers

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.