Sites for Change

By Anna Lena Phillips

Thousands of Superfund sites are designated as active by the U.S. government. An online project will highlight 365 of the worst

Thousands of Superfund sites are designated as active by the U.S. government. An online project will highlight 365 of the worst

DOI: 10.1511/2008.73.290

New-media projects offer fertile ground for experimentation. But in this growing field, works that successfully integrate substantive scientific and aesthetic principles can be hard to find. One ongoing project that demonstrates the potential for new insight as well as genuine public engagement is the Web site Superfund365 (http://superfund365.org).

Brooke Singer

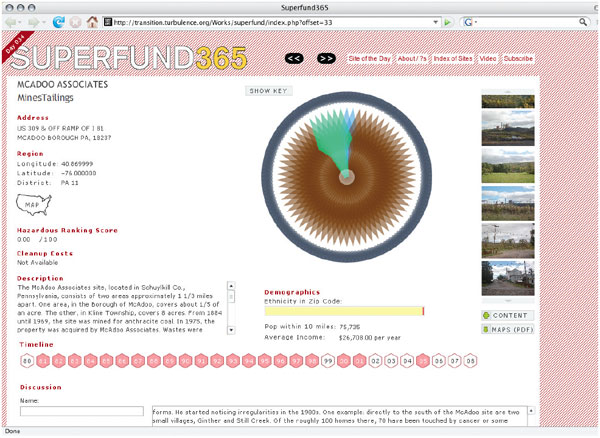

Brooke Singer, a visual artist and professor in the new media program at Purchase College, part of the State University of New York, was commissioned to create the site for Turbulence, a Web site showcasing Internet art. Superfund365 went live last September; since then, it has featured one Superfund site each day. Bringing together Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) data on Superfund sites, census data about human populations near the sites, Google maps, photos, site descriptions and user-generated content, Singer has created an interactive and user-friendly way to present complex, important data about potentially hazardous sites.

Superfund, the U.S. government's toxic-waste cleanup program, was implemented in 1980 after the Love Canal disaster. Much work has been done since, but considerable amounts remain. Taxes created to pay for Superfund expired in 1995 and have not been renewed, and despite some appropriations made since then, the fund has been weakened further by $14 million in budget cuts over the past three years. "Superfund is not so super any more," Singer says dryly. Still, she thinks of the fund as a way to frame a conversation about toxic contamination.

Superfund365's design is fresh, with clean lines, bright color and clear, elegant data presentation that would make Edward Tufte proud. Contaminants and the parties responsible for their presence are displayed as pointers arrayed in a colorful circular graph; when viewers mouse over the pointers, information is revealed, and clicking on a contaminant pointer opens the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) page for the substance. A timeline across the bottom of each page shows actions taken for the featured site.

Viewers can interact with the Web site in several ways. A comment section is set up on each of the site's pages, and users can also easily upload photos. This combination of aesthetic appeal and essential information has drawn a wide range of people to the site—from researchers to residents of communities near specific Superfund sites. Richard Hammond, webmaster for the EPA's Southeast Superfund region, notes that the site offers "an informative and well-designed presentation of materials"; he particularly likes the pinwheel graph.

As Singer decided which sites to include—those that made the cut are among the 411 sites ranked the most toxic by the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit, nonadvocacy group—she thought hard about how to present such information to a general audience. "I tried to reimagine what that interface should be like so it's not only publicly accessible but publicly engaging," she says. In the process of collecting material, she found gaps in available data as well as inconsistencies—"names of contaminants, for example, varied, making it difficult to do an accurate search for them." She relied on the EPA's databases and Superfund hotline, and she enlisted the help of managers of individual sites. "Some people have been very open, happy to help and dedicated, while others didn't return phone calls and were less than helpful," she says.

Starting near New York City, Superfund365 has progressed from site to site in a roughly geographical manner. By the end of the project, viewers will be able to follow its trail from New York to Hawaii. Some pages have had heavy traffic—especially those whose communities are already mobilized.

One such place is Stratford, Connecticut, home of the 34-acre Raymark Industries manufacturing plant Superfund site, which boasts 102 distinct contaminants including arsenic, lead, pyrene and benzene. Waste from the plant was disposed of at numerous residential and commercial sites around the town. Stratford residents are actively involved in efforts to keep the EPA working on site cleanup, and some have uploaded photos and text to Superfund365.

Another place where community members have been active is the McAdoo Associates Mine Tailings site above Hometown, Pennsylvania (screenshot above). Whereas Stratford's concerns are focused on cleanup, McAdoo residents are most concerned about possible links between disease in their community and the Superfund site that overlooks the town. Sixty-six contaminants are present in the site's soil, groundwater and solid waste.

The area has abnormally high rates of a rare cancer, polycythemia vera; residents who were already active in lobbying for more health testing contacted Singer before she arrived to document the site. A yearlong study by the ATSDR found no links between the cancer and the site, but as Singer points out, that doesn't mean that no link exists. Residents continue to work for more tests. She has kept in touch with them and follows their progress, mentioning it in presentations to other communities.

Other sites featured on Superfund365 have received less attention—"there are plenty of places where people have no idea" that there's a Superfund site close by, Singer notes—but she plans to keep the project live after the year is up, so there is the potential for it to provide a chronological record of cleanup and remediation efforts that will sit alongside the site-to-site narrative that emerges over the course of the year.

One of the project's strengths is its online format, which offers access to an "immediate mass audience, a platform for discussion, a place to aggregate local knowledge." But the greatest asset for concerned residents may be the project's combination of online and person-to-person interaction. Though Singer hopes more people will use the site's interactive features, many have preferred to contact her directly "to see how we can collaborate to get more attention brought to the issue." Especially since the dissolution of the EPA's ombudsperson position in 2002, it can be hard for citizens to figure out what action to take. Many are "at a loss about how to navigate local, state and federal bureaucracy and get basic health studies or remediation work done," she continues.

For September, after the 365th site has been posted, Singer is planning a lecture tour during which she'll discuss many of the sites highlighted on Superfund365. She also hopes to collaborate with researchers in civil and environmental engineering to perform remediation studies at various sites. She is already working with Habitatmap, a Brooklyn-based group, to focus attention on a contamination study conducted in 2006–2007 by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. The study found several plumes of chlorinated solvents that are likely the source of toxic gases found in Greenpoint residents' homes. Such "street science" can help residents of affected communities determine what can be done, even when lack of funding and other obstacles slow the government's response.

The Web site may serve as a model for future work. "I do encourage scientists who are approached by artists to be open to such collaborations," says Singer. "I don't know any examples of scientists approaching artists, but that would be interesting to see." While you're planning your own ambitious project, it might be worth checking to see just how close you are to one of the most hazardous Superfund sites. And although I won't recommend, as the site lightheartedly suggests, taking a picnic to your local Superfund spot, visiting with camera in hand might not be a bad idea.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.