This Article From Issue

July-August 2008

Volume 96, Number 4

Page 344

DOI: 10.1511/2008.73.344

The Unnatural History of the Sea. Callum Roberts. xviii + 435 pp. Island Press, 2007. $28.

If men could learn from history, what lessons it might teach us! But passion and party blind our eyes, and the light which experience gives is a lantern on the stern, which shines only on the waves behind us!—Samuel Taylor Coleridge, December 18, 1831, Table Talk

If we could indeed learn from history, then The Unnatural History of the Sea would transform stewardship of the world's oceans. In this comprehensive account of commercial fishing over the centuries, author Callum Roberts skillfully weaves a net far finer and greater than that of any previous author, casting it more widely around the globe and further back in time, bringing up for our inspection enormous and enigmatic marine creatures, daring explorers and exploiters, hordes of fishers, and cynical policy makers.

Using firsthand accounts and narratives from earlier eras, Roberts is able to conjure up scenes that are more moving than those in even the best natural-history documentaries. Readers get a glimpse of the abundance of marine life in earlier times, even around the shores of America and Europe, and of the reasons for its decline. They can finally begin to understand why it is now the case that "camera crews filming ocean wildlife must travel thousands of kilometers to witness spectacles that were ordinary and familiar to people in Dampier's day." (British explorer William Dampier lived from 1651 to 1715.)

The book takes the reader on a voyage around the world, charting exhaustively the relentless plunder of species after species, stock after stock, from the 11th century to the present. Roberts pays particular attention to the early decline of freshwater fish in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries, which motivated the move to sea fishing. He also tracks the reactions of the early explorers to the Americas. The Frenchman Jacques Cartier, for example, describing what he saw on a visit to Canada's Madeleine Islands in 1534, wrote that

[W]e went down to the lowest part of the least island where we killed about a thousand of those Godetz [gannets] and Apponatz [great auks]. We put into our boats so many of them as we pleased, for in less than one hour we might have filled thirty such boats with them.

This type of reaction to the discovery of new resources is fascinating. My first thought was to attribute the early colonists' inclination to plunder to their sheer excitement at such marvelous abundance. However, watching the theme of discovery and decimation play out in the book over hundreds of years, I was forced to conclude that human greed is the cause, for the destruction continues despite rising knowledge and awareness. For example, although it was clear at the time that pauses in fishing during the First and Second World Wars allowed North Sea stocks to recover and catches to increase, the British government ignored the scientists who argued after the wars that fishing efforts should not be renewed to previous levels.

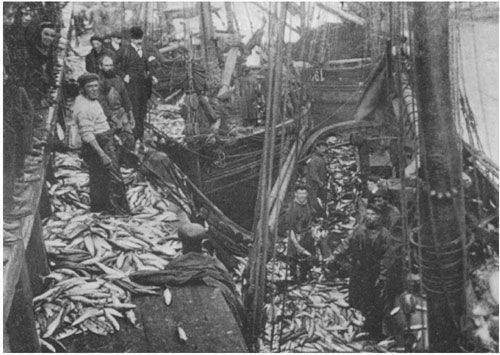

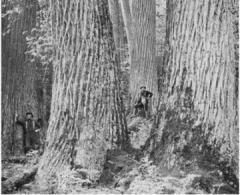

From The Unnatural History of the Sea.

Roberts is particularly good at conveying how crippled and farcical past attempts to legislate fisheries have been. British fishers have been protesting trawling for more than 500 years, testifying in large numbers at inquiries about the destruction caused by dragging a net over the seafloor. Roberts goes into great detail about two of these inquiries: In 1863, the British government appointed a Royal Commission to examine complaints about trawling. The commissioners concluded that no new restrictions were needed. They also advised that all previous Acts of Parliament regulating fishing should be repealed. Just 20 years later, in 1883, another Royal Commission of Inquiry had to be convened because of evidence of the depletion of fish stocks after the advent of steam trawling. That inquiry commissioned a study, but after a decade the flawed research exonerated trawling as the cause of the depletion. When it comes to exploiting the seas, it does seem as though "passion and party blind our eyes."

Just as I was beginning to experience seasickness on the book's seemingly endless voyage of exploitation, Roberts abruptly dumped me on the rather dry land of current fisheries management. Modern fishing is a complex social and political issue, but Roberts glosses over the complexities, coming up with seven solutions. He particularly focuses on one of these: the creation of areas closed to fishing (marine reserves), a subject on which he has published many articles. His tour of fisheries management is so brief that the reader is forced to take these solutions on faith, with little debate. Many readers will accept them readily, though, having been convinced beyond doubt that past and ongoing exploitation needs to be rectified.

More disappointing than Roberts's brief treatment of fisheries management is his failure to link the solutions he offers to the history of fishing he has so carefully constructed. He leaves unanswered how we might integrate this newly synthesized knowledge of past stock abundances and past human behavior into current fisheries management.

The Unnatural History of the Sea is unprecedented in the extent to which it reconstructs the past state of nature using historical accounts. The book has great power to move people to save what is left and perhaps even restore what has passed. Unfortunately, Roberts's tinny summary will leave readers unconvinced as to how to proceed. But with his illuminating light now on the stern, scientists and policy makers may yet use this knowledge to chart a better way forward.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.