This Article From Issue

July-August 2007

Volume 95, Number 4

Page 368

DOI: 10.1511/2007.66.368

The Shock of the Old is a pathbreaking work—full of promise, but also somewhat disturbing. The subtitle, "Technology and Global History Since 1900," captures the volume's broad and arresting perspective, suggesting its concern with "asking questions about the place of technology within wider historical processes." The word shock in the provocative title alludes, I suppose, to contradictory pressures between new and more traditionally measured sequences of time and change, which are prominent in the book's panorama of interacting themes. This book is a bold and necessarily preliminary reconnaissance, in brief, in the direction of a comprehensively contextualized view of technology.

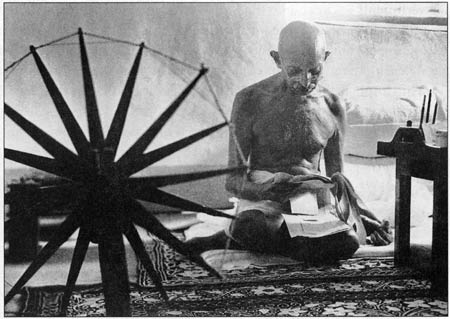

From The Shock of the Old.

The broad strokes of this portrait are invitingly sprinkled with examples chosen for their vividness (rickshaws, shifting preferences for means of committing suicide) rather than for the contribution they make to the development of central themes in more convincing detail. But those broad strokes, placing global macroeconomic and technological trends in their common settings, call convincingly for further attention. They should stimulate interest, particularly among anthropologists, in venturing further into cultural as well as ecological predispositions and constraints, which receive only passing attention here.

There are surprising juxtapositions in any reconnaissance. One of the longer and more satisfying examples of the potential of author David Edgerton's approach is his discussion of the transformative effects of refrigeration. This material is improbably tucked into a chapter on "Killing" (which is separate from another on "War"). The discussion ranges from insecticides through the transformation of fishing from an unchanging simplicity of ancient methods into the strip-mining of fish colonies and the transformation of small, local slaughterhouses into "reeking factories of death," and on to genocide. The account of the industrialization of the commercial killing of livestock and the transportation and consumption of meat, in which cold storage played a crucial part, eloquently illustrates the impressive transoceanic complexities by which immense, truly global transformations in scale were achieved—so that by the end of the 20th century, 240 million tons of meat per year were being produced.

Edgerton has chosen to focus on the 20th century. A longer account that embraced the Industrial Revolution as well would have been desirable. But he already has a lot to work with: two world wars, the Depression, the withering of imperialism, the rise (and also the stumbling) of many new nations—and in the rich ones, a growing preoccupation with scientific and technological advances purporting to drive globalization. He is at pains to argue that these great processes and events do not form a smooth, inexorable continuum and thus cannot be encompassed by a single, integrated narrative. Offering a few summary statistics, particularly on economic growth and rising or declining rates of change in national productivity, he is attentive not only to reversals and regional disparities but also to the widespread, secular decrease in upward slope across all the later decades of the century.

At the heart of Edgerton's approach is a sweeping preference for use-centered rather than innovation-centered history. "Alternatives exist for nearly all technologies," he says, and on a worldwide scale he shows that those alternatives are combined, persist vigorously and even reappear in new combinations across a span of many decades. Clearly, historians of technology need to be concerned with seeking greater breadth, rather than merely highlighting "firsts" and novelty—but how far should they go in the direction of Edgerton's universality? If attention is focused on firsts in invention and on innovation, the history of technology tends to be confined to a handful of countries and even centers within them. If the focus is on the vast array of uses and adaptations of those inventions and innovations, history is, potentially at least, to be found almost everywhere. Technology then would be specifically engaged with the totality of the world's population, which as Edgerton points out is "mostly poor, non-white and half female."

The effect of focusing on a very widespread coexistence, persistence and variability of uses and their modifications is highly positive in one important respect. Uses are inextricably a part of broader economic patterns, and for centuries economies have been a subject of serious measurement. Comparison of economic performance and trends across nations and regions thus readily becomes a surrogate for plotting the changing pace and significance of otherwise much more elusive inventions and innovations. Crude though that surrogate is, the author admits he is at a loss to find a better one. And invention becomes an even more elusive subcategory within the very broad and long continuum of innovation from stylistic change to more fundamental improvement.

But this approach is also troubling. The author fails to deal with the subject of patents, but (with some difficulties at the margins) patenting has to address directly issues of originality and effectiveness. In return for favorable judgments, it bestows economic incentives. But there is no consideration given in Edgerton's account to the need for a structuring of incentives, nor even to the complex roles of markets in largely directing the diffusion, adoption and historical impacts of the creative discoveries that ultimately energize the system. Are these always promptly self-evident, or at least inevitable? How much do accidents of timing and "market imperfections" matter? Do broad macro-economic flows somehow correctly recognize ideas that are potentially transformative, so that as a result those ideas will regularly attract the means to develop and sustain themselves?

Or are more detached judgment of inherent quality, breadth of critical view and an eye on the longer term also necessary? And how do we assure the preservation and enhancement of these qualities into succeeding generations? These, of course, are the functions claimed by and usually assigned to universities. But as Edgerton cogently argues, universities certainly have no unique claim on originality or inventiveness. His concluding substantive chapter, on "Invention," makes this point with heavy emphasis.

The belief that science is the source of new technologies, that it requires the breaking of new ground, and that it is centered in universities is, Edgerton believes, one that has come to the fore only in the years since World War II. This "very particular innovation-centred view" currently finds its major foci in particle physics and molecular biology. As he sees it, investigation of those subjects, which is largely the direct product of unprecedented governmental funding, reflects "only a tiny proportion of twentieth-century academic research" and hence is not representative of the larger situation. "The great bulk of invention—let alone the development of inventions—takes place, and always has done—a long way from university research laboratories," he notes, "in the world of use...and under the direct control of users."

It would be hard to dispute this assertion. But critical detachment and a concern for long-term hierarchies of quality are still important. Quantum mechanics and the double helix provided standards of rigorous thought to rally around—standards that have reached out far beyond the sciences and even the universities.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.