Engineering and the Human Spirit

By Domenico Grasso

A well-rounded curriculum might produce a more diverse engineering workforce

A well-rounded curriculum might produce a more diverse engineering workforce

DOI: 10.1511/2004.47.206

The campus of Smith College is one of the most pleasant places in the world to be on a sunny afternoon. The setting is so lovely, the academic atmosphere so tranquil, that when I first arrived here, I was totally captivated. The spell of the place, however, made me uneasy about my mission, which was to convince a few of the students at this premier, all female liberal arts college that they ought to become engineers. The mission, as it turned out, was destined to fail.

So began an article by Samuel C. Florman, author of The Existential Pleasures of Engineering, published in Harper's magazine in 1978. Nationally, the interest of women in engineering has not improved significantly since then. Only 1 percent of college graduates are women who have studied engineering. Only 20 percent of all undergraduate engineering majors are women. And only 6 percent of engineering professors are women.

"Look to your left and look to your right; one of these students will not be with you at graduation." This has been the common prologue to the academic career of many engineering hopefuls. In part as a result of this sieving process, we now have a situation where the United States doesn't educate enough engineers to meet its needs. In 2002, U.S. institutions of higher learning graduated approximately 69,000 engineers, yet we were nevertheless forced to attract some 25,000 more from other countries—creating a technological brain drain from many nations that can ill afford it.

Although forecasts for the future are somewhat uncertain (and some even question the need to educate more engineers), it is certain that our engineering workforce needs more diversity. In contrast with medicine and law, the engineering profession remains "pale and male," with white men making up 90 percent of practicing engineers.

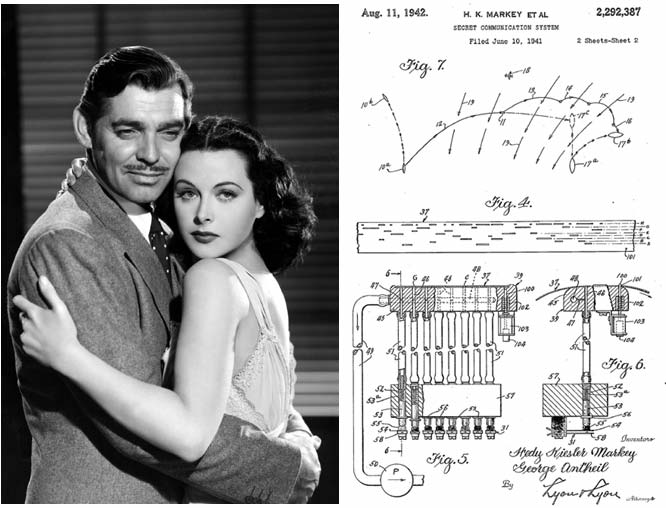

Greater diversity would help, for example, to overcome the bad-driver syndrome. Let me explain: Not so many years ago, women were accused, stereotypically, of being bad drivers. Why? Because cars were designed by men, for men—indeed, for your average 5-foot-10-inch man. Women, who are usually shorter, often could not see the four corners of the car from the driver’s seat, which may have contributed to countless numbers of fender-benders. This commonplace example illustrates how some diversity at the design table might help to avoid bad—even dangerous—designs.

The quest for greater diversity in engineering explains why in 1999, on the same bucolic campus described in the pages of Harper’s 21 years earlier, the faculty voted to establish the first and only engineering program at a women’s college. They were proving Sophia Smith (founder of Smith), absolutely right when she said in 1870 that the college will have curricula "as coming times … demand for the education of women and the progress of the race." Educating women in engineering is surely a case in point.

Today Smith boasts a student body comprising nearly 5 percent engineering majors. Five of the nine engineering faculty are women. And in May of this year, Smith will graduate the first engineering class in U.S. history that is composed entirely of women.

Many of these women will go on to join the ranks of the engineering workforce, bringing with them an array of concerns and insights that their male counterparts might lack. Of course, some of these women, as Florman bemoaned back in 1978, will not choose to become engineers, for a variety of reasons. My colleagues and I at Smith are convinced that an engineering education will serve a woman well no matter what path she chooses in life. And it will also serve society. If information is the currency of democracy, informed thought and intelligent decision-making must be the currency of a sustainable civilization. Indeed, as former Harvard president Derek Bok noted, "Of all our national assets, a trained intelligence and a capacity for innovation and discovery seem destined to be the most important." Engineering, a cornerstone of Bok’s "innovation and discovery," teaches one form of reasoning, one of many. I would argue that the way engineering students learn to think is especially valuable.

And what after all is engineering thought? A common misperception is that engineering is another one of the sciences. It is not. Engineering decisions rarely hinge entirely on science. Rather, engineers must also consider many other factors such as economics, safety, accessibility, manufacturability, reliability, the environment and sustainability, to name a few. Engineers must learn to manage and integrate a wide variety of information and knowledge to make sound decisions.

Engineers at Smith learn that such decisions must be tempered by an element that is often lacking in the education of engineers—the human spirit. Their education reflects the admonition of Robert Pirsig, author of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, who believed that technology should not be "an exploitation of nature, but a fusion of nature and the human spirit into a new kind of creation that transcends both."

At Smith, we define engineering as the application of mathematics and science to serve humanity. This definition necessarily requires that our graduates appreciate the human condition. Our program is noted for the same quantitative rigor as those at leading universities but is also distinguished by the way our students fuse Pirsig's "nature and the human spirit." In the education of Smith engineers, the study of the humanities and social sciences is just as important as the study of the physical sciences and mathematics.

Harvard biologist E. O. Wilson once asserted that "the greatest enterprise of the mind has always been and always will be the attempted linkage of the sciences and the humanities." At Smith, this challenge has become the organizing principle for our engineering program. We make it clear to our students that engineering is the application of science to enrich the human condition. Indeed, a sense of social relevance and social responsibility pervades the entire engineering curriculum.

But how can we teach these students everything they need to know in just four years? By handing out a lot of homework? Probably not. Instead, the faculty tries to help students hone their critical thinking using techniques usually associated with study in the liberal arts and through structured problem solving, which is typically associated with an engineering education. In this way, we provide students with the tools and the desire to be continuous learners. Thus, long after their detailed recollections of the Navier-Stokes equation and the Pieta have faded, Smith engineering graduates will still retain an ability to think critically and to learn more about a subject on their own.

How do we teach them those skills? The Smith faculty does not apply one particular method, recognizing that there are a variety of modes of reasoning and styles of presentation that prove to be effective. We feel that the more exposure students have to various ways of thinking, the better equipped they will be to succeed.

So, rather than forcing them to pick one specialty from a smorgasbord of engineering degree programs, we offer a single degree, a B.S. in Engineering Science, which focuses on the fundamentals of all the engineering disciplines. With rigorous study in the three basic areas—mechanics, electrical systems and thermochemical processes—students learn to apply first principles to structure engineering solutions to a variety of problems. Complementing this technical rigor, our faculty expects that the students' work will be informed by the diversity of thought that they have acquired from their classes in the humanities and social sciences. In short, the engineering program at Smith is designed to diversify the ranks of America's engineering professionals (and of those who sit at the highest levels of government and corporate America) in intellect as well as gender.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.