This Article From Issue

May-June 2021

Volume 109, Number 3

Page 134

Conversations in the first half of 2021 are dominated by COVID-19 vaccines: where they are being distributed, who has had the coveted shots, and how life will change after the majority of adults have been vaccinated. The journal Science even chose RNA-based vaccines as their “2020 Breakthrough of the Year.” These developments are, of course, highly welcome, and they could not have been achieved without a key event that occurred 150 years ago but that is now virtually forgotten: the discovery of nucleic acids, DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) and RNA (ribonucleic acid). This finding marked the start of a new era in our understanding of organisms and disease. But the story also holds lessons in how we remember those who bring about breakthroughs.

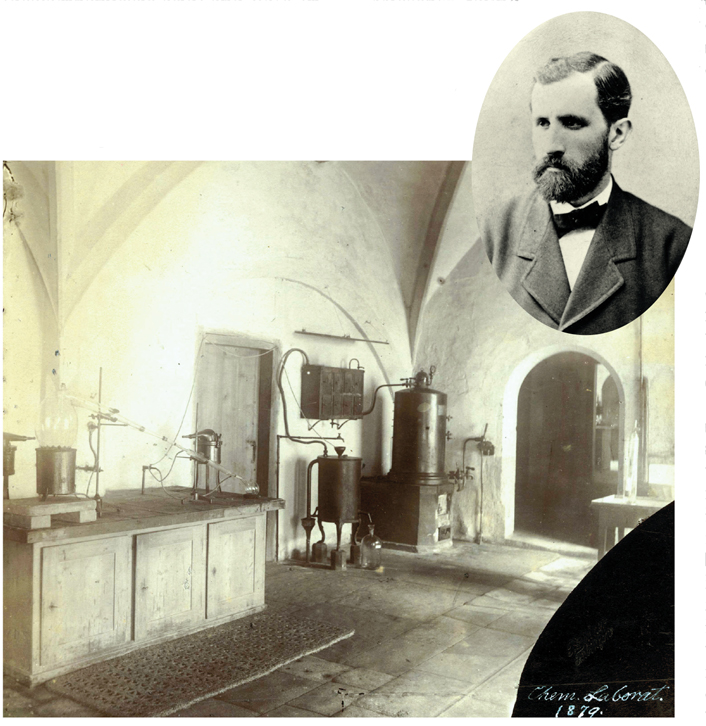

In the winter of 1869, Friedrich Miescher (1844–1895), a young Swiss doctor, was working in the former kitchen of a medieval castle in Tübingen, Germany. His aim: to uncover the chemical basis of life. He used pus-soaked bandages from a local hospital to first isolate cells, then their nuclei. From the latter, he extracted an enigmatic substance. When analyzing it, he found that it had chemical properties unlike any molecule described before. (See “The First Discovery of DNA” for more about Miescher’s methods.)

Courtesy of the University of Tübingen and Ralf Dahm

Miescher found that nucleic acids were present in the nuclei of every cell type he studied. He also noticed that the amount of DNA increased in proliferating tissues, including tumors, and he briefly speculated that DNA might play a role in fertilization and the transmission of heritable traits. When he published his discovery in 1871, Miescher was so convinced of the significance of the new substance that he considered it “tantamount in importance to proteins.”

These insights were prescient at the time; it is hard to make a bigger discovery than DNA. Indeed, DNA is so central to how we think about biology today that it has become the icon of the life sciences and is deeply embedded in our culture. Yet, very few know of Miescher and his discovery. By contrast, James Watson and Francis Crick—the scientists who revealed the structure of DNA—have achieved almost rock star–like fame.

There are several reasons for Miescher’s relative obscurity. In some ways, his discoveries were just too far ahead of their time. For decades, DNA, which is composed of only four building blocks, was considered too simple a molecule to encode the complexity of life in all its forms. Instead, the proteins, comprising 20 amino acids, were favored as carriers of hereditary information. Only in 1944—75 years after Miescher’s discovery—did scientists show that DNA is the genetic material. At that point, the race was on to understand how DNA encodes information. But it took another nine years before Watson and Crick uncovered the structure of DNA: the now iconic double helix.

Coincidentally, 2021 marks another anniversary in the history of DNA research: The first drafts of the complete human genome sequence were published 20 years ago by the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium and the firm Celera Genomics. This event was another landmark for the life sciences and biomedicine. It also ushered in the era of big data in biology. Huge datasets produced by various genomics projects around the world have transformed our understanding of how we develop, age, and become ill. (See “Turning Junk into Us,” for one application.) They also further our comprehension of how life evolved and how ecosystems function. Thanks to genomics, scientists have made major steps toward Miescher’s dream of understanding the chemical basis of life.

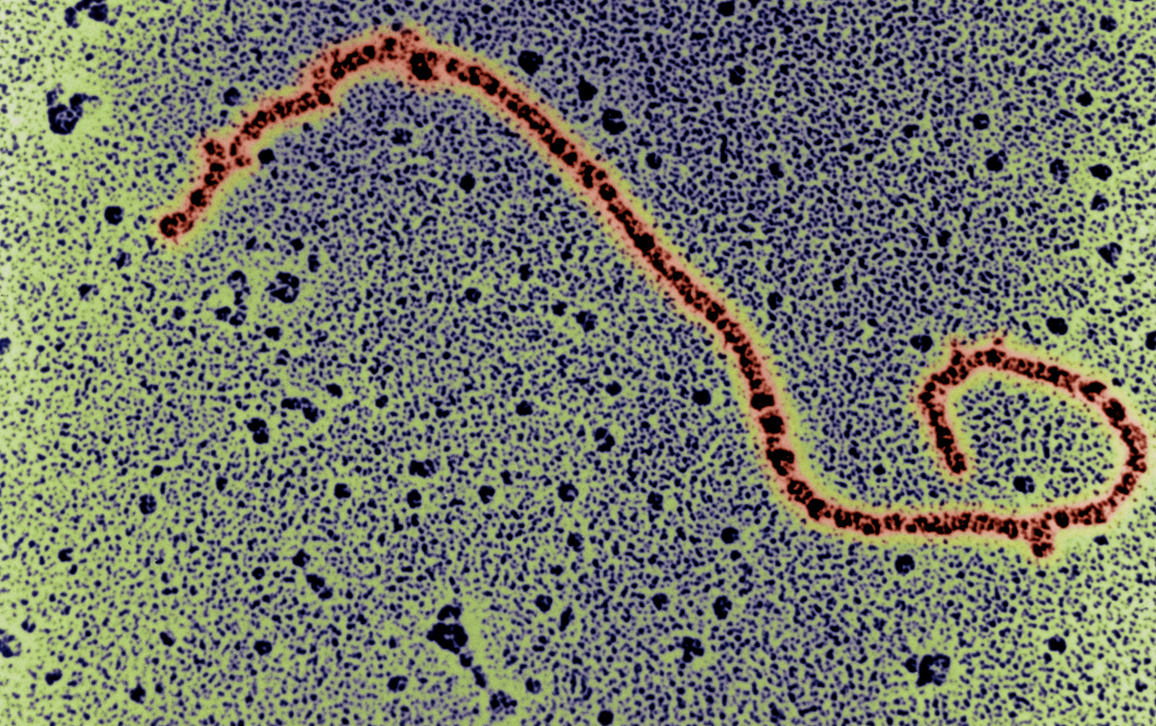

Science Source

In recent years, molecular genetics has led to the development of new, personalized treatments for a variety of diseases. Innovations such as CRISPR-based genome editing have opened the door to a new era of genuine precision medicine. Moreover, RNA-based vaccines, such as those currently employed to fight COVID-19, may prove equally effective at combating cancer and other major diseases. A century and a half after Miescher first announced DNA and RNA to the world, scientists are not only making great strides toward understanding the operating instructions of living beings, they are also increasingly able to treat diseases in ways unimaginable only a few years ago.

Given that these groundbreaking developments are based on Miescher’s seminal discoveries, it is all the more surprising that he is so little known today. Aside from being too far ahead of his time, another reason for Miescher passing comparatively unnoticed may be his disinclination toward engaging in communication and self-promotion. Unlike Watson and Crick, who were gifted communicators, Miescher was introverted, gave few talks, and did not interact much with colleagues. He published little and when he did, he wrote long and convoluted papers with key messages often buried deep in less important details. Thus, we can learn a lesson from Miescher’s story: Even the greatest discoveries require effective and accessible communication for them to be noticed and remembered.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.