A Geologist Looks at the Stones of Jerusalem

By Arie Issar

Building a new dream for the promised land

Building a new dream for the promised land

DOI: 10.1511/1998.37.0

During the late 1960s I was involved in the exploration for groundwater in the semi-arid Nordeste province of Brazil. Once, while traveling to a drilling site, the driver of my Jeep asked me what place on earth I came from. As I had already learned that the name Israel meant nothing to many people in this remote part of the country, I told him that I was born in Jerusalem, where I now lived and worked. He stopped the car, looked at me and said, "No, señor, you must forgive me, but you are either joking or, God forbid, lying. We were told in our church that Jerusalem is in Heaven." Fortunately I had my passport, which stated that I was born in Jerusalem on the 13th of July, 1928—and more fortunately, my driver could read. He studied the written document, shook his head a few times and then continued to drive to the site, still shaking his head and murmuring to himself from time to time. I gathered that this poor fellow was going through a process of changing his whole attitude toward my city of birth.

Paul A. Souders / Corbis

Now, nearly 30 years later, I realize that there is no need to travel to a remote corner of the globe to shock people with a new conception of Jerusalem. I learned this after I published an article in the Israeli daily newspaper Haarets in which I suggested that the old city of Jerusalem should be turned into a center for learning of international law and the promotion of international peace, rather than a place where Jews, Christians and Muslims clashed over their differing beliefs. I stressed that holy sites could and should maintain their status, but that there were many places inside the city's walls that could serve as scholarly institutions, where students from all over the world could come to study law.

To my surprise, people who were otherwise open to new ideas strongly disapproved of my suggestion, arguing that the people of the three religions would never accept such an idea. As it turned out, I did not get any reaction from religious fundamentalists or fanatical nationalists. Was my suggestion too ridiculous to be worthy of consideration? Were my views so different from those of the other residents in the old city?

I asked myself how it was that someone such as me—born and raised in Jerusalem in an orthodox-tolerant Jewish family—was ready to consider a new Jerusalem when others were not. After all, like all orthodox Jews for the past two millennia, I had prayed during my youth that Jerusalem and its Temple should be rebuilt so that all Jews might one day return and restore the ancient rites of sacrifices. The old city also holds many deep memories for me. I remember studying for high-school exams with a friend on the rooftop of my parents' apartment, overlooking the hills of Jerusalem. When it came to the Bible and history exams, we were able to look around and see the very places that were mentioned in the books—from the time of Judges, to the kings of Judea, to the Roman era.

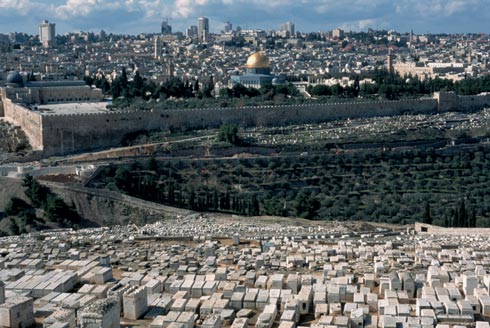

And I cannot pretend to be aloof to the feelings that a man has to his homeland and to its stones. I was elated to tears, as were other members of my reserve army unit, on the day of the Six-Day War when we heard on the wireless that "the Mount of the Temple is in our hands." And after many years of traveling and visiting other cities, I still admire the view of Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives in the early and late hours of the day when the oblique rays of the sun emphasize the golden reddish color of the city's stones.

David H. Wells / Corbis

At the same time, I know how dangerous the conservation of ancient attitudes can be, especially when it comes to the adoration of ancient stones. Part of my change in attitude comes from the fact that the Jewish people did gain their independence and that the new Jerusalem is a flourishing capital of the state of Israel. But I also think that my attitude toward rocks and stones in general, and those of Jerusalem in particular, changed when I became a geologist. I know this with certitude because I remember the way I looked at the massive stones of the colossal Wailing Wall just a few days after the Six Day War. I had come back to the old city after being away for 20 years, the period when it was under Jordanian rule. When I stood in front of the wall I found myself wondering which geological strata the stones were quarried from. It was also with the eye of a geologist that I appraised the rock at the base of the dome of the Mosque of Omar; I could see that it dated to the Upper Cretaceous. I could appreciate this rock with a certain air of scientific detachment even though it played a special role in Jewish tradition—indeed, one could write a book on the legends, traditions and myths attributed to this rock.

Today Jerusalem is again in the center of a political and religious controversy. Once again one hears many words about the holiness of the stones of this city. One can guess that in the future, as in ancient times, words about holy stones will cause more bloodshed that will in turn make these stones even more holy to many people.

How ironic that the holiness attributed to the stones of Jerusalem has caused this city to witness so much bloodshed, cruelty and other atrocities, at the same time that it has inspired prophecies of human and international justice. Many years ago the prophets Isaia, Hosea and Micha foresaw a time when Jerusalem would be a center for judgment between nations and for justice among the people, making them beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. As a scientist I regard prophecies as foresight and intuition.

Of course, it takes more than stones to build a palace of peace or a center of international law and justice. Stones become what they are according to the beliefs and the ideas of the men and women who live among them. If enough people come to believe that the stones of Jerusalem can be turned into buildings that accommodate justice and peace, then perhaps these ideas may overwhelm the will of the people who maintain that the stones of Jerusalem are holy only to them.

The sad question now is how much more blood will be spilled over the stones of Jerusalem before enough people come to the conclusion that this city—whose archaic root, Ir Shalem, means the "city of peace"—should become a cornerstone of peace on earth, rather than in heaven.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.