Short takes on three books

By David Schneider, Christopher Brodie, Amos Esty

Over the Mountains: An Aerial View of Geology · Ham Radio's Technical Culture · Middle World: The Restless Heart of Matter and Life

Over the Mountains: An Aerial View of Geology · Ham Radio's Technical Culture · Middle World: The Restless Heart of Matter and Life

DOI: 10.1511/2007.65.280

OVER THE MOUNTAINS: An Aerial View of Geology. Michael Collier. Mikaya Press, $29.95.

"You could spend a lifetime hiking and exploring," says Michael Collier, "and only just begin to understand how mountains fit into the rest of the world." Fortunately for Collier, he can fly. In Over the Mountains, the benefits of having a pilot's license become clear, as Collier provides dozens of photographs taken from his Cessna (such as that of Alaska's Johns Hopkins Glacier, right) to complement his discussions of the geological processes that have shaped the peaks of North America.

From Over the Mountains: An Aerial View of Geology.

Collier explains clearly how erosion, uplift and other such forces have created the skyline of the natural world. He points out that the Appalachians once stood much higher than they do today but have been worn down over millions of years. California's Mount Whitney, part of the younger Sierra Nevada range, is currently the highest point in the Lower 48, but Collier remarks that this, too, is temporary. As with flying, taking the long view chronologically gives him an unusual perspective and "a sense of wonder." Even from the ground, Over the Mountains makes it easy to understand his enthusiasm.—Amos Esty

HAM RADIO'S TECHNICAL CULTURE. Kristen Haring. The MIT Press, $27.95.

Since the earliest days of radio, amateur operators ("hams") have worked the airwaves for no other purpose than the pleasure it brings them, over the years developing a culture that is mostly male, geeky, apolitical, open and altruistic. In Ham Radio's Technical Culture, historian of science Kristen Haring examines the roots of these qualities.

She says, for example, that the culture of helping out one's fellow citizens was intimately linked to the public-relations value of such activities. American hams were forbidden to operate their rigs at all during the Second World War, and afterward they were viewed with suspicion, as if anyone with a radio transmitter hidden in the garage just had to be a foreign spy. To dispel the notion that their occasional chats with their counterparts behind the iron curtain indicated disloyalty, some American amateurs threw themselves into the civilian defense effort. Who better to provide rudimentary communications after a thermonuclear exchange than your friendly neighborhood ham? Providing assistance during natural disasters was a natural extension.

From Ham Radio's Technical Culture.

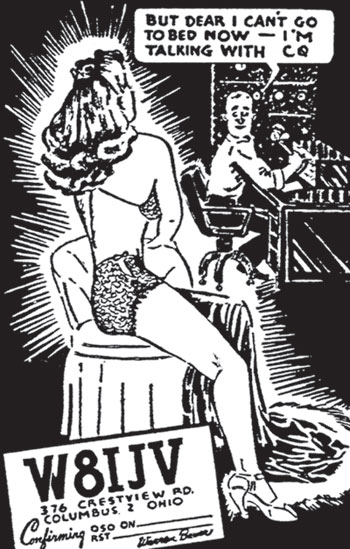

Haring also points out that the fundamental activity of these hobbyists—idle chatter—was something stereotypically associated with women, making this largely male group very self-conscious about the implications of neglecting their girlfriends and wives in favor of connecting with other men. Would outsiders view them as homosexuals? One ham (W8IJV, above, right) clearly saw the humor in the situation, as evidenced by the preprinted cards he sent out to his radio contacts.

Haring's prose is dry, scholarly and full of repetition. A few troubling errors on technical matters (for example, a botched explanation of why some audiophiles still prefer tubes to transistors) make one wonder how much understanding of radio and electronics she has. And despite covering many angles well, she overlooks an essential motivation for taking up such hobbies—a thirst for knowledge about how the world works and a taste for things that are technically sweet.—David Schneider

MIDDLE WORLD: The Restless Heart of Matter and Life. Mark Haw. Macmillan, $24.95.

Middle World, a zippy account of the past 200 years of science, takes as its theme the growing understanding of Brownian motion, that unending dance of microscopic particles. The "middle world" of the book's title refers to the realm of "middle-sized" objects such as pollen particles, DNA, proteins and viruses—things small enough to dance in water. Author Mark Haw is a materials scientist who studies the behavior of matter at this "mesoscopic" scale, which he defines as ranging from a hundredth to a thousandth of a millimeter.

Haw begins his account with the story of Robert Brown, the Scot who first described the nonstop jiggling of tiny particles in water (his tests included pollen, soot, dust from the Egyptian Sphinx and scrapings from his teeth). Exactly why tiny things cannot keep still was a question that initially stumped 19th-century scientists, but finding the answer helped prove the atomic theory of matter. The mesoscopic scale is fashionable again today, given the interest of biologists and nanotechnologists in the workings of cells filled with middle-world objects.

Haw writes in a fast-paced, witty, staccato style, studding his account with vignettes of the great minds who, in the span of a few decades, flung science into the modern era. He does a particularly good job of helping readers swallow great chunks of chemistry and physics without the mental indigestion that usually goes along with such a feast.—Chris Brodie

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.