This Article From Issue

March-April 2005

Volume 93, Number 2

DOI: 10.1511/2005.52.0

Blackett: Physics, War, and Politics in the Twentieth Century. Mary Jo Nye. x + 255 pp. Harvard University Press, 2004. $39.95.

At the heart of Mary Jo Nye's thought-provoking biography of British physicist and Nobel laureate Patrick Maynard Stuart Blackett is the question of whether science and politics mix. In exploring Blackett's life, Nye portrays a researcher, political adviser and scientific leader willing to take risks, move into new areas of research and speak out on matters of politics and war. In doing so, she addresses the important question of how (and at what price) one can reconcile a scientific career with political activism.

Born into the "kindly security" of the middle class in Edwardian England, Blackett entered the Royal Naval College in 1910 at barely 13 years of age. War broke out in 1914 as he was finishing his exams, and he then began serving on board warships. He witnessed the Battle of Jutland in 1916, and seeing the few survivors from the 1,200-man crew of the HMS Queen Mary floating in oil-stained water gave him a visceral appreciation of war's cost. However, he was never a pacifist, although he did later become a socialist.

Blackett entered the University of Cambridge in 1919, and in 1921 he began postgraduate work at Ernest Rutherford's famed Cavendish Laboratory. In addition to studying physics and mathematics, Blackett showed a growing interest in politics. Nye smartly places him amid the intellectual and political milieu of Cambridge between the wars and notes that he soon became known as someone unafraid to speak out on controversial issues. In talks he gave as part of a BBC radio series on science, he argued that scientists could not separate their work from politics, and as Hitler expanded his grip on Europe, Blackett urged his colleagues to prepare themselves for war.

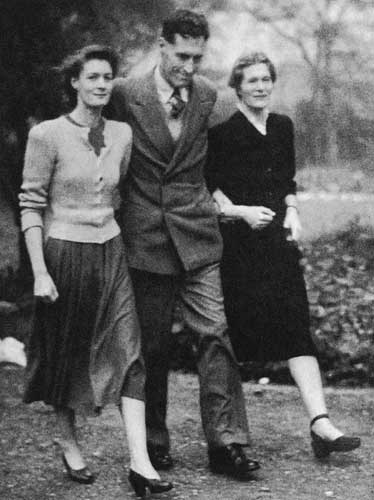

From Blackett

Even before World War II broke out, Blackett was applying his research skills to defense efforts. He helped develop Britain's air defense network through the establishment of radar stations, and in the process he became a staunch advocate of operations research, which he defined as "the analysis of data in order to give useful advice." With information gained by studying the effects of U-boat attacks, shipping convoys and aerial bombing, he helped shape Allied military strategy and save soldiers' lives, often struggling with military officers who resisted advice from civilian "boffins."

His analysis of data also sowed the seeds for his disagreements with others regarding American nuclear strategies. Blackett, who served on England's Advisory Committee on Atomic Energy and its successor, the Nuclear Physics Committee, as well as on the Chiefs of Staff Subcommittee on Future Weapons, opposed British development of atomic weapons and favored a neutralist foreign policy and cooperation with the Soviet Union. His objective analysis of the overhyped effects of Allied bombing made him skeptical of U.S. postwar plans to deter Soviet aggression by threatening to incinerate civilian targets. He achieved notoriety for suggesting that the United States had bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki primarily to intimidate the Soviets. His stances, publicized in his 1948 book Military and Political Consequences of Atomic Energy (which was published in the United States as Fear, War and the Bomb), earned him the enmity of politicians and military leaders on both sides of the Atlantic, but by the 1960s some of his controversial views had entered mainstream thinking.

In separate chapters, Nye carefully addresses Blackett's scientific career. While at the Cavendish, as part of a research program in nuclear physics he experimented with cloud chambers, which detect high-energy particles passing through a supersaturated vapor. With a young Italian scientist, Giuseppe Occhialini, he designed a cloud chamber controlled by Geiger-Müller counters, a valuable tool for cosmic-ray research. In 1933, Blackett and Occhialini confirmed the discovery of the positron by Caltech physicist Carl Anderson. Blackett and Occhialini's work was said by some to constitute an independent discovery of the positron, but Blackett's habitual caution and skepticism delayed publication of their research, and Anderson was awarded priority and given the 1936 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work. Blackett had to wait another 12 years for recognition of his accomplishments: In 1948 he received the Nobel for "his development of the Wilson cloud chamber method, and his discoveries therewith in the fields of nuclear physics and cosmic radiation." Nye goes behind the scenes to illuminate the politics of the Nobel selection process.

Blackett linked his military work and his scientific research. Cosmic-ray experiments, like operations research, required one to see patterns in data on a global map and to coordinate research on global and local scales simultaneously. His wartime experience paid off even as he turned away from cosmic-ray research to explore new scientific topics such as geophysics and the study of continental drift.

Blackett believed that a physicist "must be enough of a theorist to know what experiments are worth doing and enough of a craftsman to be able to do them." Nye, in addition to describing Blackett's scientific successes (as well as his failed attempt to demonstrate that the magnetic fields of the Sun, stars and Earth are a fundamental property of their rotating masses), also illuminates his style as a researcher and scientific leader. Blackett favored "small science," carrying out research with modest-sized magnetometers and cloud chambers rather than the massive tools of postwar Big Physics. He believed that a good lab was "one in which ordinary people do first class work," and he worked hard to ensure that his own institutions at Imperial College and Manchester University were such places.

Blackett's charisma as a scientific leader reminds one of anotherscientist who did valuable war research only to be pilloried for hispostwar views—Robert Oppenheimer. The two men met as members of a Cambridge science club in 1926, and although they were not particularly close, they remained friends for the rest of their lives. Blackett, much more so than Oppenheimer, emerges as a character of great inner strength. Through his willingness to disavow his own grand theory of magnetism and to speak out on atomic weapons and America's foreign policy, Blackett put his personal interests at risk to preserve his own convictions and integrity. By displaying his commitment to science and society through his moral courage, Blackett exemplified the modern scientist acting as a good public citizen.—W. Patrick McCray, History, University of California, Santa Barbara

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.