This Article From Issue

March-April 2005

Volume 93, Number 2

DOI: 10.1511/2005.52.0

Soft Machines: Nanotechnology and Life. Richard A. L. Jones. viii + 229 pp. Oxford University Press, 2004. $29.95.

Conversations about nanotechnology invariably wander, ranging variously from science fact, on to scientific speculation, and often into science fiction. These are truly the glory days for nanoscale science. Scientists and engineers, artists and authors, dissidents and dreamers all make important contributions to nanotechnology, stretching its potential and defining its limitations. Nanotechnology has opened a new world filled with possibilities: new realms of discovery, new avenues for technical development and endless scenarios for storytelling. I am reminded of 20th-century space science, which captured the imagination of experts and amateurs alike, turning scientific progress into a source of national pride and making the starship Enterprise seem every bit as real as Apollo 11.

From Soft Machines

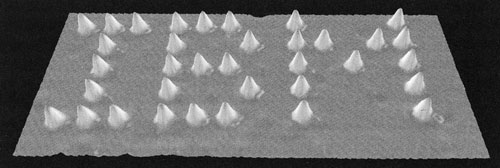

Richard A. L. Jones, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Sheffield, has provided a new entry to the burgeoning literature on nanotechnology. In Soft Machines: Nanotechnology and Life, he touches on a variety of subjects in this ever-widening field. These include, to use his classification, top-down methods (such as photolithography of silicon), which are now reaching nanoscale levels; bionanotechnology, "the 'Mad Max' or 'Scrap-heap challenge' approach to nano-engineering"; biomimetic nanotechnology, which takes its lead from biology but uses the tools of chemistry for construction; and the "radical nanotechnology" of mechanosynthesis in the style of K. Eric Drexler (author of the influential 1986 book Engines of Creation).

Like a knowledgeable host making dinner conversation, Jones moves from topic to topic with a stream of lively banter. We ask "What is it like down there?" and our host tells us about Brownian motion and dispersion forces, using Raquel Welch in Fantastic Voyage to spice up the conversation. When the discussion turns to molecular electronics, we get a healthy dose of a recent science fraud scandal. When the topic is diamondoid structures, we all smile, put in a quick plug for our favorite science fiction novel and move on to more serious topics.

The book sparkles when the author turns to his own passion, the properties of polymers. You can feel his excitement as he presents the odd behavior of responsive gels and block copolymers. We watch chains unfold and refold as rubber is stretched. My favorite part of the book is his description of India ink. In a graphic paragraph, he shows us how chains of gum arabic keep those messy black carbon grains mixed into a smooth, flowing solution.

The description of biological nanomachines is less compelling, however, because it is framed in the most general terms. Jones never delves into the nanolevel details, in spite of the fact that many biological molecules are characterized at the atomic level. Graham Johnson's beautiful illustration of myosin function is one of the few glimpses the book provides of the thousands of molecular structures that are currently known. However, the reason for the cursory description is clear: Jones has set himself a lot of ground to cover and has only a few pages within which to fit it. Amusingly, he recounts that biologists working in cell signaling "seem to have completely lost their grip when it comes to nomenclature," citing such names for signaling proteins as Groucho, Hedgehog and Dishevelled. It's easy to become mired in the fascinating details when studying the biological realm, but Jones manages to avoid this common pitfall.

The book's mantra is its continual return to Brownian motion. Jones states that "Brownian motion is a feature of the nanoworld that nanotechnology will just have to learn to live with." He revels in the way biological nanomachines harness this randomness—in motors, in pumps, in assembly, in transport—and he chides Drexler-style nanotechnology for ignoring it and instead imposing macroscale physics on the nanoscale.

By the end of the book, Jones's vivid descriptions and diverse examples have made me a believer. He tells us again and again to look inside cells for inspiration, for methods and for raw materials when faced with this challenging new world. Biological evolution may not have found the best possible solutions to problems of nanoscale engineering, but as Jones says at the close of the book, "I would be very surprised ifwe can do better."—David S. Goodsell, Molecular Biology, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, California

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.