This Article From Issue

March-April 2005

Volume 93, Number 2

DOI: 10.1511/2005.52.0

Symmetry Comes of Age: The Role of Pattern in Culture. Edited by Dorothy K. Washburn and Donald W. Crowe. xxx + 354 pp. University of Washington Press, 2004. $60.

Embedded Symmetries, Natural and Cultural. Edited by Dorothy K. Washburn. ix + 189 pp. University of New Mexico Press, 2004. $69.95.

On a visit to the Alhambra some years ago, I toted along a copy of Symmetry in Science and Art, a weighty text by A. V. Shubnikov and V. A. Koptsik, as a field guide to the carvings and tilings that decorate that extravagant palace overlooking Granada. The two books under review here would probably serve as better field guides—Symmetry Comes of Age even includes a useful flowchart for classifying the symmetry groups of patterns—but I suspect that the authors and editors would not entirely approve of this use of their work. The tourist who stalks the halls of the Alhambra trying to complete a checklist of the 17 two-dimensional symmetry groups is not their ideal student of "the role of pattern in culture." When one is looking at an artifact such as a tiled floor or a woven fabric or a beadwork ornament, identifying crystallographic groups is at best the beginning of understanding the object. The classification might tell you something about the meaning of the work in the context of Western mathematics, but it is unlikely to reveal much about the object's meaning within the culture that created it.

This point is made emphatically by Branko Grünbaum—a mathematician who certainly knows his symmetry groups—in a previously published article on ancient Peruvian textiles that is reprinted in Symmetry Comes of Age. Grünbaum argues that group theory offers little help in understanding the Peruvian patterns because

The concepts of that theory are entirely out of tune with the modes of thinking of the people whose products are being investigated; moreover, these concepts were totally absent even from the thinking of mathematicians during most of the history of mathematics.

He goes on to rail against "the stifling dictates of the 'symmetry is group theory' cult," writing that

It is aggravating to see sophisticated examples of patterns, made by cultures for which the patterns held great importance, considered as inferior or "mistaken" just because they do not fit some mathematicians' preconceived notions of "symmetry."

The idea of outsider critics pointing out the "mistakes" of native pattern makers is turned upside down in another essay in this volume, by Peter G. Roe, an anthropologist. Roe writes on the geometric designs of the Shipibo people of the upper Amazon basin. In the 1980s he presented a selection of Shipibo motifs to a class of art students at the University of Delaware and, with the assistance of an early computer-graphics system, had the students generate new patterns in what they took to be the same style. The computer made it easy to apply various symmetry transformations, such as reflections and rotations, but it could not enforce other kinds of design rules. Roe took printouts of the students' work back to South America, where Shipibo women and men were asked to evaluate them. The result of this ingenious experiment was not really a surprise, but it is nonetheless instructive: Patterns that look essentially alike to the untrained (or unacculturated) eye can evoke very different responses from insiders who understand the art form at a deeper level. A pattern might well have the right symmetries but still fail to win the approval of the Shipibo judges. In particular, the experiment called attention to "a nonverbalized rule in Shipibo art" requiring a certain kind of connectivity in patterns, allowing "one's finger or eye to trace a continuous line as it meanders through the lattice."

Roe reports that the requirement of connectivity has a clear meaning in the lives of the people who decorate their homes and belongings with these patterns. "The continuity of the formline ... does not let contagion intrude," he writes; "designs are supernatural armor, a Shipibo's most important protection from bewitchment and death." An explanation in such terms—at odds not just with mathematics but with the whole tradition of Western rationality—tends to emphasize our remoteness from the Amazonian way of life. But keep in mind that less exotic cultures make equally dogmatic and arbitrary aesthetic judgments about decorative patterns, and the explanations offered are no better. In our own culture, for example, a quite narrow spectrum of patterns and color combinations is deemed acceptable for men's neckties. A Wall Street banker could doubtless classify any given tie as wearable or not but probably couldn't articulate the reasons any more sensibly than could Roe's Shipibo informants. (And, as Grünbaum would point out, neither the banker nor the Shipibo would explain their preferences in the vocabulary of mathematical group theory or crystallography.)

From Symmetry Comes of Age

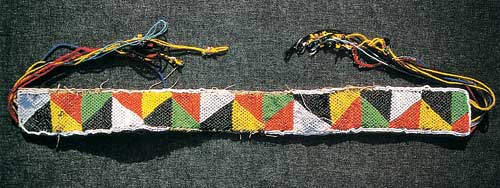

In another chapter of Symmetry Comes of Age, Frank Jolles of the University of Natal in South Africa examines the colors and patterns of Zulu beadwork, again discovering hidden design rules. (In some cases, the rules are apparently hidden even from the designers.) Jolles focuses extended attention on a particular beadwork belt (see illustration on facing page) of a type worn by women after the birth of their first child. As beaded garments go, it is not particularly intricate or impressive, but understanding the decisions that went into its construction makes a good puzzle. At first glance, the belt pattern seems to be composed of 15 adjacent rectangles, split along zigzag diagonals so that each rectangle breaks into two triangles of contrasting color. Closer examination, however, shows that the diagonals don't actually reach the corners of the rectangles, and so the triangles are imperfect; they are really wedge-shaped trapezoids. Here is a case where the siren song of symmetry might tempt one to see a "mistake," but Jolles makes clear that the reduced symmetry of trapezoids rather than triangles is surely not an accident or a defect; it was part of the plan.

The arrangement of colors in the belt also suggests a not-quite-perfect symmetry. The trapezoids come in five colors, assigned in such a way that various rotations, reflections and translations are almost symmetries of the pattern, but in each case the symmetry breaks down when you look more closely. For example, the red trapezoids have a center of twofold rotational symmetry—a point where twirling the belt by 180 degrees returns red trapezoids to all the same positions—but that rotation scrambles the other colors. The green and the white trapezoids share a symmetry operation called a glide reflection, but again the partial symmetry fails to preserve other colors. And so the question arises: If these symmetries, which seem like the obvious ones to Western eyes, did not determine the placement of the colors, then what is the rule that guided the fabrication of the belt? Jolles proposes that the underlying principle is the division of the five-color spectrum into two families: red and black on the one hand and white, yellow and green on the other. The paramount rule is to assign the colors so that no two trapezoids that share an edge have colors from the same family. The color families have an interpretation in Zulu culture that seems appropriate to the belt's function: The red-black family represents female fertility and the white-yellow-green family is associated with courtship, love and youth; thus the repeated juxtapositions of like with unlike seem to celebrate sexual union and childbearing. But it should be noted that this is merely Jolles's inference about the meaning of the pattern. When he interviewed the maker of the belt, he reports, "Neither she, nor her friends, nor any of the older women who were present, were able to give any information about the piece."

A few minutes of playing with the coloring of the belt pattern suggests there must be still more unstated rules, beyond the requirement of color-family exogamy. The rule forbidding like-with-like adjacencies could be satisfied in a trivial way by simply discarding one color from the white-yellow-green family and repeating the other four colors in a regular sequence. Presumably this scheme would not earn approval from the makers of the belt. Perhaps there is also an unstated rule that all five colors must be used and that they should be distributed as evenly as possible. In that case, the observed belt pattern is a plausible solution, although certainly not the only one, or the most symmetrical one. As I continue to look at this object, I have a persistent urge to "improve" it, which probably indicates that I still don't understand what goal was in the maker's mind.

Symmetry Comes of Age is presented as a sequel to an earlier volume by the same pair of editors, Symmetries of Culture (University of Washington Press, 1988), but in some respects the new book seems more like a dialectical response. The 1988 volume emphasized the identification and analysis of symmetry patterns in cultural artifacts; it was mathematics for anthropologists. This new work is more anthropology for mathematicians. Of the 10 chapters, only the introductory one by coeditor Donald W. Crowe puts mathematics out front; it is a guide to the two-dimensional symmetry groups (including the handy flowchart for field identification). The volume grew out of a 1999 workshop on "symmetries of patterned textiles" held at the University of Wisconsin, and so it is no surprise that cloth is the most common medium of expression discussed in these chapters. Carrie Brezine, who is both a mathematician and a weaver, writes a complement to Crowe's mathematical tutorial: Her chapter is a guide to the capabilities of the loom as an instrument for generating symmetrical patterns. In subsequent chapters, Paulus Gerdes writes on Yombe woven mats, Mary Frame on Nasca embroidery, E. M. Franquemont and C. R. Franquemont on weaving in the Andean village of Chinchero, and Patricia Daugherty on Turkish-Yörük weavers. Outside the world of cloth, coeditor Dorothy K. Washburn discusses patterns on Inca-era ceramics from Peru. Although Symmetry Comes of Age began with a symposium, it is more cohesive and coherent than a typical proceedings volume.

Embedded Symmetries, Natural and Cultural also derives from a symposium, held in 2000 at the Amerind Foundation in Arizona. Some of the same themes and authors reappear: Peter G. Roe and E. M. Franquemont contribute chapters, and Dorothy K. Washburn is both an author and the editor. Some of the same ancient Peruvian fabrics discussed by Grünbaum are analyzed here by Anne Paul. But three introductory articles offer a point of view quite different from that found in Symmetry Comes of Age, a point of view oriented at right angles to both the mathematical and the anthropological approaches to symmetry. Diane Humphrey describes studies of the developmental biology of symmetry. Infants as young as four months seem to show a preference for patterns with certain kinds of symmetry. Michael Kubovy and Lars Strother examine the perceptual psychology of symmetrical patterns; for example, they point out that when we see a frieze pattern that has both a twofold rotational symmetry and reflection symmetries (it can be brought into coincidence with itself either by a 180-degree turn or by a mirror reflection), the mirror symmetry seems to take precedence. Finally, Thomas Wynn looks at the cognitive development of symmetry over the course of human evolution, citing evidence in stone tools and cave paintings.

Both of these books are eye-openers. I am inclined to describe Symmetry Comes of Age as a basic text, and Embedded Symmetries as important supplementary reading. If you must choose between them, it's only fair to note that Symmetry Comes of Age offers brighter paper, better illustrations (including some in color) and twice as many pages for $10 less.—Brian Hayes

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.