This Article From Issue

March-April 1998

Volume 86, Number 2

DOI: 10.1511/1998.21.0

Homoplasy: The Recurrence of Similarity in Evolution. Michael J. Sanderson and Larry Hufford, eds. 339 pp. Academic Press, 1996. $69.95

"Homoplasy" is a term invented more than a century ago by E. Ray Lankester to denote correspondences among organisms evoked by similar environments. Today often defined in terms of what it is not—as similarity that is not homology—homoplasy is therefore an impediment to the reconstruction of phylogeny. The editors of this volume sought to establish homoplasy as a topic of interest in its own right and to identify the evolutionary processes that produce it.

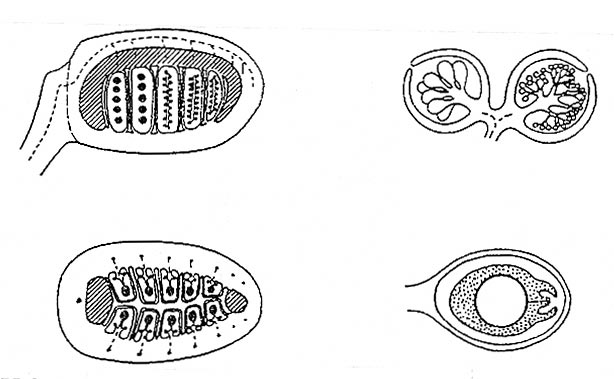

From Homoplasy.

In his cogent introduction, David Wake identifies two groups of issues that arise in the study of homoplasy: how to detect it and how to explain it biologically (a distinction that applies equally to work on homology). Several chapters focus on methodological issues. James Archie reviews in detail the properties of various indices commonly used to measure homoplasy in characters and in data sets. From a survey of botanical papers, M. J. Sanderson and M. J. Donoghue show that in practice the Consistency Index (which they choose as a measure of homoplasy) and bootstrap support (which they see as an index of confidence or robustness of a cladogram) vary, counterintuitively, independently of one another. Joseph Chang and Junhyong Kim devise their own index—the probability (within a given data set) that two taxa with identical character states share that state by chance rather than by descent—and compare its behavior with other indices.

Chapters by R. Bateman, Scott Armbruster, Peter Endress, L. Hufford, and Susan Foster et al., provide a wealth of case studies, analyses of characters on cladograms dominated, refreshingly, by botanical examples. As Dan Brooks points out, homoplasy is observed at different levels in the systematic hierarchy and may be explained in terms both of constraints—how the characters themselves are structured biologically—and of recurring selective factors in the ecological environments of the organisms. Questions such as "what biological processes or properties enhance the occurrence of homoplasy?" are examined from the perspectives of character complexity (in a formal analysis by Dan McShea), heterochrony (Hufford) and character function (Foster et al. on display versus nondisplay behavior and Armbruster on attracting resin- or fragrance-collecting pollinators). Heather Proctor finds that it is not perceived lability but lack of availability of behavioral characters that accounts for their scarcity in phylogenetic studies. She makes the interesting points that the most abundant source of behavioral data is behavioral ecology, not systematics, and that ecologists choose characters defined broadly so as to maximize the probability of homoplasy. Jeff Doyle shows how the different historical processes in which genes, characters, sexually reproducing organisms and species participate can produce conflicting, but nevertheless biologically informative, character distributions.

Like homoplasious characters, certain themes recur in various contexts throughout the book, and a one-line summary does a disservice to a thoughtful treatment. This is a useful book, strong on practical, methodological considerations, with several chapters that transcend observations specific to particular systems to deal with more general issues. This may be the first, but one hopes not the last, book-length treatment of this compelling topic.—V. Louise Roth, Zoology, Duke University

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.