This Article From Issue

January-February 2016

Volume 104, Number 1

Page 52

DOI: 10.1511/2016.118.52

THANK YOU, MADAGASCAR: The Conservation Diaries of Alison Jolly. Alison Jolly. 424 pp. Zed, 2015. $27.95.

I’m going to pay for this. I followed the two local guides back into the forest, away from the overlook where we had just sighted two female silky sifakas and their belly-clinging, black-faced infants. Silky sifakas are critically endangered lemurs, distinguished by their plush white fur and tiny global population; worldwide, approximately 250 adults remain. My attempt to answer whether wildlife populations were continuing to decline at a long-term research site in Madagascar using camera traps and lemur surveys had only just begun. This was my second day in the field, and already I had a photograph that should have taken the full two months of the planned survey to get. Still, I was certain this luck would come at a price—maybe a few terrestrial leeches attached somewhere terrible, like under an eyelid.

There’s not much worse than terrestrial leeches anywhere near your face. Well, except for the price I actually paid.

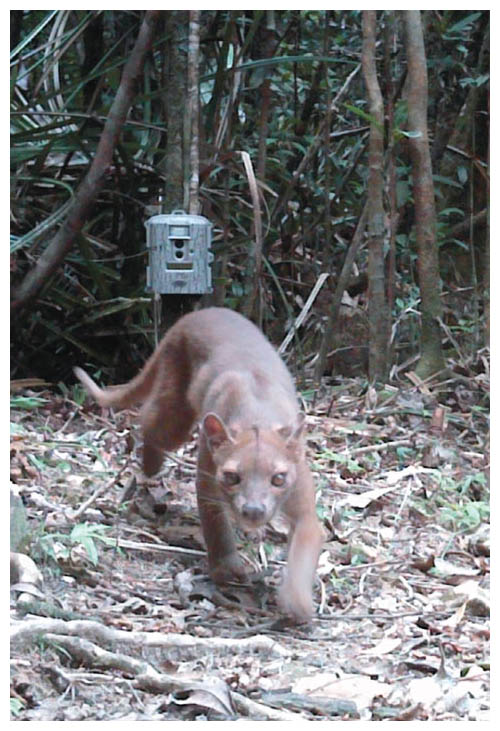

Photograph courtesy of Asia Murphy.

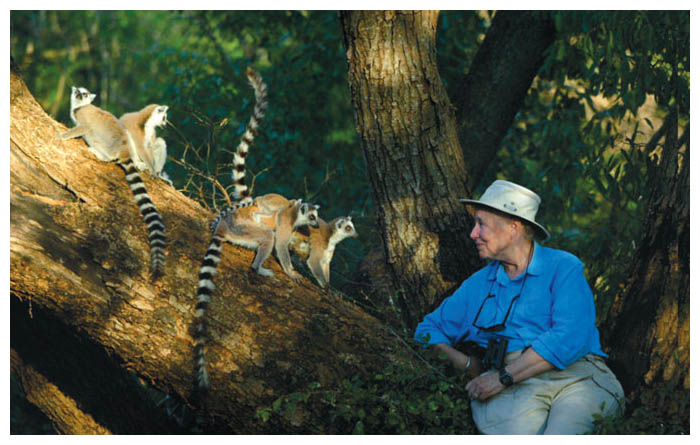

Much like the world-renowned primatologist Alison Jolly, I study the imperiled wildlife of Madagascar. (I am, however, neither world-renowned nor a primatologist.) The island nation—home to numerous species found nowhere else in the world, including lemurs—is the setting of Jolly’s posthumously published conservation diaries, Thank You, Madagascar. She was a postdoctoral student when her research first took her there in the 1960s to study the famous ring-tailed lemurs. To give you a picture: Imagine King Julian from the 2005 DreamWorks movie Madagascar, except in actual 3D instead of 3D animation and without the Indian accent. Also, King Julian should have been Queen Julia. In the book’s introduction, Jolly’s daughter notes that this was a plot detail Jolly relished discussing, probably because her research on ring-tailed lemurs recorded the first evidence of females in a primate culture having dominance over males of the species. Later studies revealed that it is something of a rule among lemurs for females to be in charge. That was big news in 1960s primatology. While James Brown was singing that this was “a man’s world,” male lemurs (including silky sifakas) were getting bopped on the nose for any disrespect, real or imagined.

Jolly’s time in Madagascar extended well past the normal time allotted for a postdoctoral appointment—because, as the country often does, it captivated her. It took her hostage and did not allow her to leave, at least not for good. After her postdoctoral research, she returned regularly until her death in 2014, feeling drawn by Madagascar’s wonder and mystery, continuing her research, and getting mixed up in conservation and politics.

Thank You, Madagascar’s core material comes from Jolly’s field diaries, written over the course of 50 years and organized thematically. During the final months of her life, she dictated reflections on the moments the diaries describe; these are interspersed throughout the book and provide useful context. The diary entries are insanely detailed, yet the book never bogs down in minutiae. As Jolly’s tale unfolds, ranging across the island and through the decades, she presents the full scope of her experiences—from a moonlit party (complete with betsa-betsa, the Malagasy equivalent of moonshine) held on the Masoala peninsula in the early 1960s to scenes from the devastating 2010 famine brought on by drought in the arid southwest; from teetering above a raging river on a bridge no wider than Jolly’s foot to listening in on a boardroom filled with movers and shakers, including World Bank representatives, who typically wield their power from behind the scenes. The book presents itself as fairly standard memoir, with its cover image of a smiling Jolly face-to-face with ring-tailed lemurs and their piggybacked young and with a warm foreword by Hilary Bradt of Bradt Travel Guides, a major backer of Madagascar charities. (Bradt, incidentally, mentions that Jolly defied the “soulless scientist” stereotype. Ahem.) Yet the book amounts to more than the sum of its wildly detailed parts. It’s not just Jolly’s memoir; it’s a memoir of the conservation movement in Madagascar. It extends beyond the personal to capture cultural, political, scientific, and environmental history. That said, this history is shaped by its historian’s perspective: astute, humorous, observant, optimistic, and admittedly narrow.

Photograph courtesy of Asia Murphy.

If I were to hazard an estimate, I’d say the book’s composition breaks down along the following (okay, unscientific) lines: 35 percent travelogue; 5 percent name dropping of Madagascar’s scientific Who’s Who; 25 percent comedy; 30 percent history of attempts at conservation, aid, and research in Madagascar; and 5 percent sober musings on the island’s future in the face of climate change, continued population growth, and very recent political instability. The book’s five sections—“Villages,” “Politics,” “Environment and Development,” “Weather,” and “Money”—lead readers through time, space, and topic. The first section, “Villages,” brings the reader in on the ground floor, examining various aspects of Malagasy culture and how it intersects with wildlife conservation and informs the Malagasy relationship with the West. “Politics” focuses on early attempts to get Malagasy and western conservationists on the same page about protecting lemurs, leading to a comically tense wrangle over the wording of an agreement. “Environment and Development” is almost exclusively concerned with the development of Ranomafana National Park in southeastern Madagascar and the effects of the park on nearby locals. “Weather” shifts gears to focus on the arid southwestern portion of Madagascar, famine, and dangers posed by climate change, and “Money” begins and ends with the real struggle of making conservation pay.

The serious and the absurd are well juxtaposed in this book. In one scene Jolly hilariously recounts the terrified attempts of Malagasy dignitaries forced to hold a large, lazy boa constrictor during a visit to an American zoo—the fear of snakes and chameleons being deeply rooted in Malagasy culture. More sobering is her disturbing portrait of locals deprived of their ancestral lands by conservationists who turned a forest into a fortress (aka Ranomafana National Park). The question of how to reconcile locals’ and conservationists’ competing priorities is a thread that winds through the book, and it’s one that remains deeply relevant. How do we conserve Madagascar’s amazing biodiversity while helping locals to sustainably develop and improve their livelihoods? How can one reconcile the (mainly Western) desire to protect exotic natural beauty with the local utilitarian view that sees a rainforest become a productive rice field and feels that there has been some improvement?

Recently, I found myself face-to-face with a noose hanging in the middle of a forest trail: a homemade trap laid for any terrestrial animal walking the path. The first thing I felt wasn’t anger at the idea of locals hunting the species I study. It wasn’t horror either. It was curiosity, about how the trap worked and how it was made. The experience reminded me of a moment Jolly describes in “Villages”, when a photographer she was traveling with expresses an interest in documenting lemur hunting. There’s a very real need to record what Jolly deemed “local culture”—and about hunting Jolly herself wrote, “It happens anyway.” But the photographer’s wish raises a valid question. If we as scientists and conservationists show anything but condemnation for practices such as hunting and tavy (the Malagasy word for slash-and-burn agriculture), are we tacitly encouraging the very activities we should be trying to stop? Conversely, is it arrogant to pose such questions, to presume that the opinion of strange Westerners has any influence on a local’s desire—or even need —to hunt wildlife for a meal?

Photograph courtesy of Asia Murphy.

The field site where I first saw the silky sifaka was one my colleagues began surveying in 2008. Early on, lemurs abounded in the trees, and our camera traps recorded thousands of pictures of various species of carnivores, ground-dwelling forest birds, and small mammals. But year after year the number of lemurs we’ve seen has decreased, and we found ourselves ecstatic over any picture of a fossa, Madagascar’s largest native carnivore. I, in particular, was heavily invested in the alarming trends I was seeing in the local fossa population, because, like the soulless scientist I am, I promptly named the individuals we saw on camera trap. The local population included a scarred old girl named Sophia, a white-muzzled female named Rose, and a young male—first seen in 2008—with a flattened tail that I watched grow up through the camera lens. (His name? Flat-tail.) Seeing Sophia, then Rose, then others disappear as the years went past felt like having a pet run away and never come back. I held onto hope that they would be seen the next year, or maybe the one after that. But because fossas are hunted by locals, I knew deep in my heart what had happened.

So I was very excited when this site was set up for ecotourism in 2014 as part of the Wildlife Conservation Society’s attempt to conserve the region’s wildlife. Maybe ecotourism could save what was left of the local fossa population. When I returned to the long-term field site, I found the trails cleaned up and labeled with charming signs, tent structures built, and bungalows with (occasionally) working toilets installed. I saw foreigners interested in viewing the silky sifaka visit the site. And as the weeks went by and the camera trap data came in, hopes that my fossa would be saved were dashed. There were only three males left on the site (thankfully, including Flat-tail).

I had believed I would pay for seeing the silky sifaka so soon after I arrived in Madagascar, and my hunch was right. The price wasn’t anything so immediate as the new bruises that emerged; the painful, itchy thorn scrapes; or a disgusting external parasite near my face. It was to wander, searching for old landmarks, through the remains of the forest I had simultaneously marveled and cursed at before. It was to stumble into clearing after clearing, homemade trap after homemade trap. It was to realize that the safety and promise said to accompany an ecotourism designation might be nothing but an illusion. It was to look into the future of this field site— my field site—and see it become a façade: the forest untouched where foreigners would tread along neatly marked trails, but degraded and alien just beyond their sight and interest. And it was to see the faded remnants of a once-burgeoning local fossa population hanging on by a thread. Although for various reasons the ecotourism designation couldn’t have come earlier, I believe it has come too late.

Conservation efforts, no doubt, will continue across Madagascar. Conservationists will teach locals how important the island’s indigenous species are, how crucial its ecosystems are. Ecotourism companies will bring in foreigners willing to pay to see these species, and the money will trickle down. The locals will put two and two together and will gain a stake in conservation. When nature “pays” (whether through ecotourism, as with my field site, or environmentally friendly mining, as Jolly details in “Money”) locals will value their biodiverse heritage. This concept is ubiquitous in conservation literature and culture. It appears in practically every grant proposal, every presentation. It’s a wonderful idea. It reflects a fairer mentality than the one underlying the old fortress-style conservation. It’s also, more often than not, nothing but a bunch of hot air. At best, it’s easier said than done.

From Thank You, Madagascar. © Margaretta Jolly 2015. Used by permission of Zed Books.

Successful ecotourism schemes depend on—among other things—ease of access, community participation, fair profit distribution, and willing, numerous ecotourists, of which there are two camps: those that want to experience nature in luxury, and those that seek adventure. Ecotourism in Madagascar isn’t developed enough to provide the luxury that tends to attract the well-to-do and is generally too expensive for the scrappy explorers. Basic human nature and corruption at the local and district level can make the distribution of whatever profits exist anything but fair. Community participation is hard to come by when short-term needs are supposed to be exchanged for long-term benefits and access to the forest is exchanged for a few guide positions given to the lucky few who are able to talk to foreigners. And ease of access? While it can certainly be fun, a six-hour boat ride up a river, a night spent on the floor of a rickety community house, and then a three-hour hike up muddy mountain trails is anything but easy.

Ecotourism schemes require careful planning, skilled execution, and more than a little luck. Above all, they need time to grow into a success. Unfortunately, if there is anything that is lacking in Madagascar—or across the world—it is time.

The question isn’t whether things will change in Madagascar; it’s how quickly, how irrevocably they’ll change. Reading Jolly’s account of the Masoala party, I was struck with a feeling of wonder. My research is in the same region, and reading about Jolly watching the local dances, hearing the local music, made me nostalgic for something that I had never seen and never will see. The Malagasy are now no strangers to global culture. They have cell phones and satellite TV; the boys sag their pants and wear brightly colored baseball caps with the brim pulled jauntily to the side. Local music is now a mix of French and Malagasy pop songs and beats more suited to a dance club—which there are, complete with cover charges and pulsing, colored lights—than an impromptu celebration in the darkness of streets lit only by the moon.

Solving the problems that hinder wildlife conservation in developing countries ultimately requires locals to cherish their wildlife and their wild places. Typically this mindset comes to the populations of nations that are developed, to people who no longer have to rely on their forests for their cooking fuel or a meal. But developing a nation requires, well, development, which historically cultures have accomplished by ravaging their own resources or the resources of another country. Even as conservationists strive to find alternative approaches that foster regional economic growth while supporting local ecosystems, solutions have remained elusive. How can a nation develop economically without destroying the ecosystems that conservationists hope a nation’s population will value? I have no easy answer to this question. Neither did Jolly.

I did not expect Thank You, Madagascar to have a working solution to the problem of conservation in Madagascar. Still, it is slightly galling to me that a woman who had a lifelong career in the field didn’t have an answer beyond notions of making nature pay. As an ecotourism destination, my field site can’t reasonably be expected to “pay” three local villages enough for them to desist cutting down trees and hunting wildlife—not until sometime in the distant future, when there may be nothing left to save. With Jolly, I saw someone wise and experienced, someone who might be able to provide a hint, a suggestion, of where to find a solution. I was left wanting.

While certainly unconventional, Jolly’s championing of eco-friendly mining in “Money” was yet another attempt at integrating local economic development and conservation. She reasoned that the public watchdog would keep mining companies from making a mess of Madagascar’s forests, and the company did try its best to make things work. However, the scheme struggled as ecotourism often struggles, facing obstacles from local communities. With recent political instability and changing material demands, mining in Madagascar—eco-friendly or not—hasn’t provided a solution to the conflict between biodiversity conservation and local development.

So what should we do? For now, cultivate a mindset of acceptance. In my opinion, Madagascar will develop much the way other countries have, and by the time the Malagasy are ready to truly value their natural heritage, much of it will be gone. I fear that future generations will read about Madagascar’s wildlife with the same sense of wonder and false nostalgia that Jolly’s quaint account of locals dancing in the darkness brought to me: a sense of having missed something lost to time and change, but not quite knowing the glory of what you had missed. Jolly, with all of her years and experience, wasn’t able to find the solution, even though she was optimistic in a way I could never hope to be. As she stated in closing, it is vital that we—scientists, the general public, Malagasy, and the global community—try, lest Madagascar’s unique ecologic legacy ceases to be a living one, found instead only in books like Jolly’s, filled with lively accounts and pictures of faded glories lost.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.