The Visual Trickery of Obscured Animals

By Judy Diamond, Alan B. Bond

In many species, stripes and splotches of concealing coloration blend almost seamlessly with the surrounding environment, providing a crucial edge in survival.

In many species, stripes and splotches of concealing coloration blend almost seamlessly with the surrounding environment, providing a crucial edge in survival.

DOI: 10.1511/2014.106.52

On a bitterly cold evening in 1914, Pablo Picasso walked with Gertrude Stein along the Boulevard Raspail in Paris when a convoy of military vehicles drove past. World War I was just in its opening phases.

These trucks and artillery were the first examples that Picasso had seen of the new military camouflage, in which various colors were combined in swirling patterns to obscure the outlines of the vehicle. Picasso excitedly proclaimed that the patterns on the trucks were an example of cubism, the avant-garde art movement that he and Stein had helped to create.

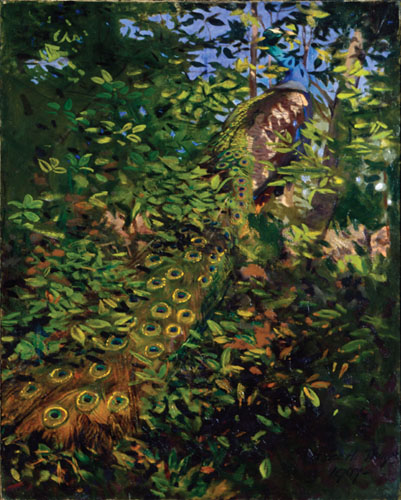

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC/Art Resource, NY

Military equipment had traditionally been colored to provide a sense of tribal or national identity. The brilliant scarlet coats of the 19th-century British army, for example, were designed to be conspicuous, to intimidate the enemy by emphasizing the number and discipline of the force arrayed against them. But conspicuous coloration was a significant disadvantage in World War I, when the opposing sides were equipped with new technologies that could inflict horrific injuries on soldiers from great distances. Military strategists began to change the way they outfitted their troops and equipment, basing their new designs on the concealing color patterns of animals.

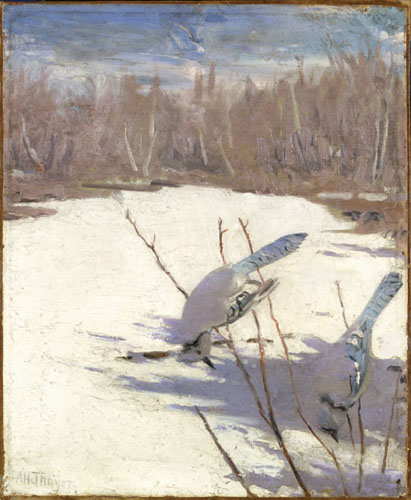

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC/Art Resource, NY

The artist most responsible for the use of obscuring patterns in military camouflage was not Picasso, nor was he even remotely avant-garde. He was Abbott H. Thayer, a prominent American painter best known for his portrayals of ethereal women and children and his landscapes of the New Hampshire mountains. Thayer was also a master at producing detailed, natural renderings of native birds and mammals. He believed that only an artist could fully understand how animals use color patterns to become invisible, and he was convinced that camouflage was essential in modern warfare.

During the war, Thayer carried on extensive correspondence with British and American government officials, sending them sketches of how ships should be painted to conceal them from the enemy and making suggestions for draping submarines in camouflage cloth. How much influence these arguments had is not clear, but both Allied navies painted many of their warships in zebra stripes, in accordance with Thayer’s principle of dazzle coloration. One of Thayer’s last books was focused entirely on the application of concealing coloration to military camouflage.

Garden Picture Library/Getty Images

Thayer’s years of wildlife illustration had convinced him that concealment is often due as much to pattern—the arrangement of the splotches, speckles, stripes, and shading that make up an animal’s visual appearance—as to the particular colors employed. His famous painting of a male peacock displayed against a blue sky and tropical foliage illustrated how a color pattern could conceal even apparently conspicuous animals in a sufficiently complex environment. Thayer contended that contrasting stripes that run out to the edge of an object fracture the visual outline, making it difficult to separate the object from its surroundings. He also thought that contrasting blobs of color within the outline of an object tend to adhere visually to matching parts of the background, thereby preventing the object from being recognized. Because both these patterns served to break up an image, they have come to be called disruptive coloration. Under the right circumstances, Thayer contended, this disruptive patterning can literally obliterate an animal’s visual appearance.

Thayer was certain of these principles because he could demonstrate them in paintings. Art did not just represent reality for Thayer. Art was purer than reality, providing a direct visual understanding that could not be obtained from just looking at a real peacock strutting across a lawn. His approach was hardly scientific, but it was very effective: The principle of disruptive coloration became broadly accepted in the scientific literature. Only recently have scientists conducted serious experimental tests of Thayer’s principles, tests that rely not on artistic insight but on the perceptual abilities of real predators.

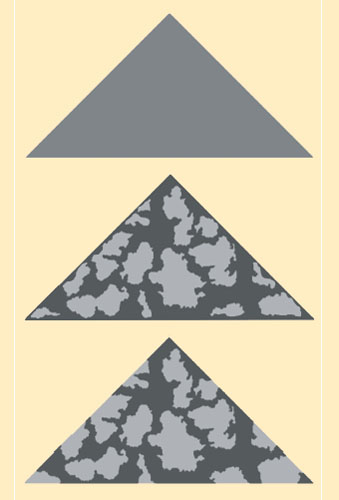

Researchers in England have tested Thayer’s hypotheses using carefully designed insect models placed in forests where they can be attacked by free-living predatory birds. Martin Stevens, at Cambridge University, and his colleague, Innes Cuthill, at the University of Bristol, wanted to determine exactly how disruptive color patterns serve to conceal prey. They created models of moths out of paper triangles, coloring them with bark-like patterns. They then attached a tasty mealworm to each moth and pinned the models to trees in an English woodland. Over the next several days, they recorded which paper moths had lost their mealworms.

Image courtesy of Martin Stevens.

Stevens and Cuthill found that the models with patterns that disrupted their outline were the hardest for birds to detect and thus retained their mealworms much longer. The task was easier for birds when the pattern was shifted so it did not touch the edges. The solid-colored models were the easiest for birds to find. Disruptive coloration did not work well on its own, however. It was most effective when it made use of colors that were drawn from the palette of the surrounding bark.

Thayer’s most famous discovery was the visual pattern now called countershading, in which the upper surface of the animal is much darker than the lower one. This pattern is found in a wide range of animals from insects to fish, birds, mammals, and reptiles. Although dark backs and light bellies had been known from early times, classical writers assumed that it was due to some unknown effect of light or temperature on pigmentation. Thayer saw that the color gradation was the exact opposite of the shading that artists apply to two-dimensional images to make them appear three-dimensional and to give the illusion of depth to their paintings.

Stan Osolinski/Getty Images

Put a uniformly colored wooden sphere in sunlight, and the top will be brightly illuminated, while the bottom is in shadow. This phenomenon is so consistent that the visual system immediately interprets the contrast as an indication of depth, causing 3D objects to appear to stand out from the background. Thayer saw that the perceptual process could be made to work in reverse. If he painted a sphere with an inverted color gradient, making it darker on the top and lighter below, and then illuminated it from above, the natural illumination pattern and the painted gradient would cancel each other out, and the sphere would appear as a flat disk. If the sphere were painted in colors and patterns that match the background, countershading would serve to accentuate the resemblance, “and the spectator,” Thayer wrote in a 1896 article in The Auk, “seems to see right through the space really occupied by an opaque animal.”

As with his paintings of disruptively colored birds, Thayer felt that the road to undeniable truth lay in direct perceptual experience. He brought his “beautiful law of nature” before the scientific community by conducting demonstrations for scientific societies using 3D sculptures. In 1896, on the lawn in front of what is now the Harvard Museum of Natural History, he demonstrated his principle of countershading to the American Ornithological Union. The secretary of the society described it in detail in his summary of the meeting published in The Auk:

Mr. Thayer placed three sweet potatoes, or objects of corresponding shape and size, horizontally on a wire a few inches above the ground. They were covered with some sticky material, and dry earth from the road on which they stood was sprinkled over them so that they would be the same color as the background. The two end ones were then painted white on the under side, and the white color was shaded up and gradually mixed with the brown of the sides. When viewed from a little distance these two end ones, which were white below, disappeared from sight, while the middle one stood out in strong relief and appeared much darker than it really was.

Abbott Thayer concluded that countershading and disruptive coloration should be recognized as "the most wonderful form of Darwin's great Law."

Thayer had arrived at his principle in an artistic epiphany, free of any evolutionary inferences. His initial publications did not even mention natural selection. But he subsequently took his exhibits on a tour of natural history museums in England, where he met Alfred Russel Wallace and several of his colleagues. During that visit, Thayer became fully converted to an evolutionary perspective. He concluded in a 1902 publication in Nature that countershading and disruptive coloration should be recognized as “the most wonderful form of Darwin’s great Law.”

Thayer had impressed scientists by demonstrating that countershading makes potatoes or wooden sculptures harder for humans to detect. But it was quite another task to make a case that countershading consistently reduces the detectability of concealingly colored prey. The range of animals that appear to be countershaded includes large marine predators, seabirds, snakes, and nocturnal mammals, species that would not obviously benefit from eliminating solar shadows. It would take experimental studies conducted under field conditions to convince modern scientists that countershading helped some animals to survive.

Observations of caterpillars by Leendert de Ruiter, a Dutch scientist, provided inferential support for Thayer’s ideas. In the 1950s, de Ruiter carefully evaluated the countershading and behavior of 17 concealingly colored species of caterpillars that feed on tree foliage in England. Roughly half of these species typically rest along the upper sides of branches and twigs, while the others usually hang upside-down from the lower sides. De Ruiter observed that the direction of countershading was perfectly correlated with the caterpillars’ favored positions: Species that stayed on the branch tops were darker on their backs; those that hung underneath were darker on their bellies. And when he brought them into the lab and shone light on them from below, they reversed their preferred orientation. This suggested that countershaded caterpillars were choosing a position that minimized the effects of shadows. It was still necessary, however, to determine whether the countershading protected caterpillars from real predators.

A group of English biologists recently put Thayer’s countershading theory to scientific test. They presented caterpillar models to birds in an undisturbed forest, asking whether the presence of countershading actually reduced predation. Hannah Rowland, from the University of Liverpool, constructed model caterpillars from cylinders of pastry dough. Each cylinder was colored either uniformly dark green, uniformly light green, dark above and light below (countershaded), or light above and dark below (reverse shaded). She pinned them along the upper surfaces of tree branches in an English forest, much as Stevens and Cuthill had done with their model moths. Over successive days, she returned to see which caterpillars had been eaten.

Rowland found that countershaded prey experienced much lower levels of predation than uniformly shaded or reverse-shaded prey. Countershaded prey were difficult to detect when their pattern could offset the effect of natural shadows, but not when they were presented upside-down. She repeated her experiments in a variety of environments and under different lighting conditions and consistently found that countershading reduced predation compared to uniformly colored, background-matching prey. Her results supported Thayer’s hypothesis, but she cautiously noted in her 2011 book Animal Camouflage: Mechanisms and Function that “the actual mechanisms by which countershading functions to reduce attacks by avian predators are still to be determined.”

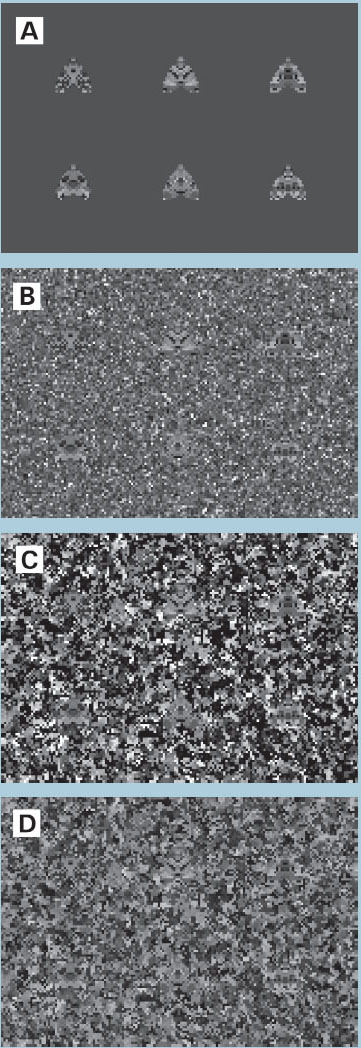

Concealment is often at least as much an effect of pattern as of color. Animal coloration usually appears as distinctive markings like the narrow stripes on grassland birds and insects, the spots on jungle cats, the leaf-sized patches of muted color on animals of the forest floor, or the fine mottled speckles on sandpipers and bottom-dwelling fishes. Such patterns echo the texture of the environment, matching the animal’s surroundings in the size and shape of color patches, as well as in the particular hues and intensities of coloration. To envision how pattern contributes to concealment, think of a digital image of an animal against its background. The image is composed of pixels of specified colors, and adjacent pixels that are similar in color will appear to the eye as patches of varying size. How well the animal blends into its surroundings is a function of the match between the color of the patches in the background and those on the animal, but blending in is also affected by the relative sizes of the patches, regardless of their color. Animals process these two kinds of visual information, color and patch size, in separate parts of their nervous system, and the information is subsequently integrated to assess the degree of resemblance to the background.

Images by Alan Bond.

How animals integrate the information about color and patch size is most impressively illustrated by cuttlefish. Cuttlefish, which are free-swimming relatives of octopus and squid, are masters at generating patterns to match their environment. They have large, complex, sensitive eyes and a sophisticated control system that allows them to rapidly modify the patterns they display. When they detect changes in their surroundings, they can change the arrangement of light and dark patches on their body accordingly. At the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole in Massachusetts, Roger Hanlon studied how cuttlefish create their remarkable patterns. In one experiment, Hanlon and his colleagues placed cuttlefish in transparent aquaria on top of complex backgrounds, such as checkerboards, stripes, or spots. They photographed the cuttlefish to determine how well they matched the background patterns, and they timed how rapidly the animals could change from one pattern to another.

Cuttlefish are unusual because they generate their own patterns even on backgrounds they have never encountered before, and they can achieve this with lightning speed.

The change was immediate. Hanlon and his team found that cuttlefish use three major body pattern types for camouflage: uniform patterns on backgrounds with little or no contrast; mottled patterns on substrates with small, highly contrasting patches like small checkerboards; and disruptive patterns that break up their outline on substrates with high contrast and long, defined edges, like large checkerboards. In the lab, cuttlefish will camouflage on any substrate, natural or artificial, regardless of whether or not there is a predator in the tank.

Hanlon asked whether the cuttlefish had preferences among background types. To ensure that previous experience had no influence in their choice, the cuttlefish were raised in the lab on backgrounds of a solid color. First, the cuttlefish were placed on a substrate that was half white and half uniform gray. In this case, the animals clearly preferred the darker substrate. When they were presented with soft sand versus sand that had been glued to plastic so the animals could not burrow into it, the cuttlefish preferred the soft sand. When cuttlefish were given a choice of three different artificial backgrounds—uniform gray, small black-and-white checkerboard, and large checkerboard—they showed no preferences, and they still showed no preferences when given three natural backgrounds: sand, small shells, and large shells. Subsequent experiments showed that cuttlefish readily integrate multiple cues from a mixed substrate (like shells of different sizes) producing a mixed camouflage pattern.

Cuttlefish are unusual because they generate their own patterns even on backgrounds they have never encountered before, and they can achieve this with lightning speed. They change their color patterns with organs called chromatophores, bags of pigment with muscle fibers radiating out around them. Each chromatophore contains one type of pigment, either dark brown, orange, or yellow. Because the organ operates with muscular contractions, color change in cuttlefish happens as fast as you can snap your fingers. A similar system occurs in most of the cuttlefish’s relatives, including octopuses and squids. Many fish have pattern-matching capabilities, particularly flounders and other flatfish that inhabit sandy ocean bottoms, but their chromatophores work on a different basis and are significantly slower. No other animal has the versatility or speed of pattern matching as the cuttlefish.

John Maynard Smith, a British mathematical biologist, outlined three evolutionary strategies to account for animal color patterns. The first strategy he termed genetically adapted coloration: When animals are adapted for life in particular conditions, and when the conditions seldom change within the lifetime of the animal, the coloration they display is fully specified in their genes. No matter what environment they are raised in, they develop the same appearance, and they do not change color when conditions vary. The sargassum animals with their elaborate seaweed-like structures and the light and dark forms of the peppered moths display genetically adapted coloration. Genetically adapted coloration is modified only very slowly, as a result of changes in gene frequencies in populations.

Danita Delimont/Getty Images

Maynard Smith termed the second strategy developmentally flexible coloration. When mammals, birds, and insects shed their outer layers of hair, feathers, or exoskeleton and replace them with new ones, they often shift their appearance. This is particularly common in response to seasonal changes. Arctic species, such as ptarmigans, arctic hares, arctic foxes, and stoats, alternate between white and brown coloration from one molt to another, in synchrony with seasonal changes in the background. Insects can switch their appearance between successive developmental stages based on cues received from the environment, such as light, temperature, or humidity. Caterpillars of the peppered moth, for example, adopt the appearance of their host plant based on the coloration of the reflected light. They molt their skins several times in the course of development, and each time, they have the opportunity to modify their appearance.

The third strategy Maynard Smith called physiologically versatile coloration. The instantaneous and varied color patterns of the cuttlefish, the disappearing acts of flatfish, and the background matching of some chameleons are all examples of animals that are able to modify their coloration almost continuously to match varying background conditions. In these species, color change is under the control of the nervous system, and the speed of response can be very fast. Many other fishes, amphibians, and crustaceans can also respond physiologically to changing environments, but the changes generally occur on a slower time scale because they are mediated by hormonal signals. African cichlid fishes, for example, change coloration as a function of the hormones that control their reproductive state. Males become conspicuously colored when they are holding territories, but when they are not breeding, they revert to a more cryptic coloration similar to females or juveniles.

The color strategy that an animal evolves depends on the variability of its environment—how predictably the surroundings change and how rapidly the change occurs. Stable environments are associated with genetically adapted color patterns that remain constant throughout the life of the animal. Seasonally variable environments can favor color patterns that are triggered by either internal hormonal changes or external cues associated with the change in seasons. Highly variable, unpredictable environments represent a particular challenge for many animals. Some, like cuttlefish and chameleons, can instantly modify their coloration, but most animals do not have this option. The spectacular color-change capabilities of cuttlefish are an extension of the physiology they share with other cephalopod mollusks. Instant transformation is not possible for mice or birds, which lack the cuttlefish’s genetic resources. As a result, coloration in many vertebrates that cope with extravagantly changeable environments is often a compromise among less satisfactory alternatives.

Although color evolution is shaped by the environment, animals are not infinitely flexible. Each species is constrained to some degree by the genetic and developmental mechanisms that are part of its evolutionary legacy, and these limit the sorts of innovation that can evolve in response to environment change. The genetic blueprint within each species contains hidden wealth, a host of processes that can be repurposed to aid visual concealment.

Animals may not achieve a perfect match to their environment, but through the course of their evolution, they often get surprisingly close.

From Concealing Coloration in Animals by Judy Diamond and Alan B. Bond. Published by The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2013 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.