This Article From Issue

March-April 1999

Volume 87, Number 2

DOI: 10.1511/1999.20.0

Glass: From the First Mirror to Fiber Optics, the Story of the Substance that Changed the World. William S. Ellis. 306 pp. Avon Books, 1998. $25.

In an era in which our computers are obsolete as soon as we unpack them, new versions of software come out before we are used to the old ones, and the newest audio-playback devices are incompatible with those of the previous decade, it is comforting to learn of the constancy and continuity of the material we call glass. The first crude glass was prepared some time in the third millennium b.c. during the ferment of technological creativity in Southwest Asia (now Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria) that previously had led to metals and ceramics. Today common metal and ceramic materials come in an impressive array of chemical compositions, but your basic glass deviates hardly a whit from the first successful recipes. You need silica (sand) as the major component, a source of sodium or potassium ions to lower the melting point to a practical range and stabilizing ions like calcium from lime to prevent the product from becoming unstable in water. The resulting soda-lime glass has marched through history essentially unchanged, with notable contributions from Egyptian, Roman, Islamic and Venetian cultures, and is still the most likely material to be found in the windows of your office and home.

From Glass.

William S. Ellis regaled the readers of National Geographic Magazine with a compelling article on glass early in the 1990s, but much was left out. In this book he now tells the complete story: glass as an archaeological or historical artifact, glass as a mass-marketed material, glass as high technology and glass as art. He uses the successful style of National Geographic by searching out and visiting the key locations of historic and modern glass developments. He interviews the participants and fleshes them out to three-dimensional personalities. He tries his hand at making, forming and smashing glass. His is a personal journey of appreciation. The only, but very significant, element missing from the National Geographic style is profuse illustrations. The book disappointingly has only one thin section containing 13 illustrations. Often I bemoaned not being able to visualize the impressive objects, whether a work of art such as the Portland Vase or a building such as the Vuitton Tower.

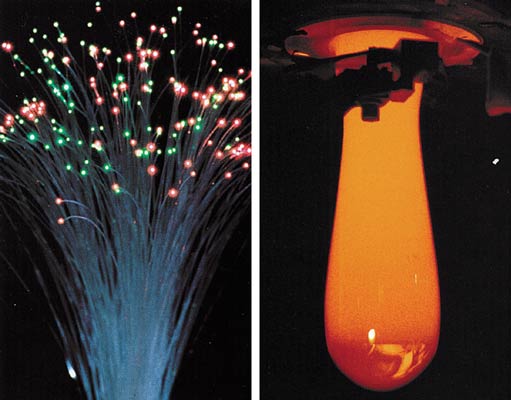

The reader is bound to be most impressed by the versatility of glass. Ellis leads us through the traditional uses of glass for containers and structural partitions (such as windows), but the chapters on fiberoptics, medicine, glass ceramics, lenses and storage of environmental contaminants bring the reader to the frontiers of current applications. Indeed, new formulations of glass are replacing the historic soda lime material in niche industries—borosilicates (Pyrex) for heat and chemical resistance, photochromic glass for variation of color, low-emissivity glass for energy conservation, glass ceramics for strength. Thus glass maintains its traditions while offering new applications through novel compositions, always based on silica.

From Glass.

Ellis gives full coverage to glass as an artistic material. Here the National Geographic heritage is strongest, as Ellis visits the artists and architects. Artistic creations in glass of course have had a long history, from small objects such as the Portland Vase to the stained-glass windows of cathedrals. Glass art, however, moved into the modern studio only in 1962, when Harvey Littleton created the small furnace that freed the artist from dependence on an industrial-sized furnace usually located in a factory. This technological emancipation led to glass-art superstars and artistic works that sell in the six digits. Glass art now is found not only in the Corning Museum of Glass but also in most major museums, elite private collections, the White House and corporate headquarters. Architectural glass also has had a long history, including the Crystal Palace in Victorian England, the buildings of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and the Vuitton Tower.

Ellis's science is usually impeccable, with some lapses (the chemist takes issue with the statement that "potassium and cesium contain similar molecules"). His pop culture is somewhat weaker (the first 3-D movie, Bwana Devil, was released in 1952, not "back in the '40s"). His style is freer than one finds in National Geographic, allowing him to be somewhat more outrageous, likening stained-glass windows to cocker spaniels (they both pass through cycles of popularity) and commenting that architectural glass separates the interior and exterior environments "like participants in soft-core porn."

The readers of American Scientist might go to this book to learn about the considerable advances in glass science and technology, but they also will come away with an enhanced appreciation of glass as a medium of art and architecture. Ellis provides an enjoyable and thorough treatment of all dimensions of glass, possibly inspiring the reader to take up glassblowing as a hobby or to invest in glass-technology stocks.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.