This Article From Issue

July-August 2004

Volume 92, Number 4

DOI: 10.1511/2004.48.0

The Reader of Gentlemen's Mail: Herbert O. Yardley and the Birth of American Codebreaking. David Kahn. xxii + 318 pp. Yale University Press, 2004. $32.50.

On taking office as Herbert Hoover's secretary of state in 1929, Henry L. Stimson discovered that the State Department included a Cipher Bureau that had been reading cryptograms sent to foreign ambassadors. Outraged, he cut off the bureau's funding and is said to have declared that "Gentlemen do not read each other's mail." One of those out of a job was bureau chief Herbert O. Yardley. So it is apt that the recently published, badly needed biography of Yardley is titled The Reader of Gentlemen's Mail.

Perhaps no one could have done so fine a job of writing this book as code expert David Kahn. Kahn is, of course, the author of the epic tome The Codebreakers, which since its publication in 1967 has been the yardstick against which cryptologic history must be judged. His writing is always carefully crafted and meticulously researched, and this new book is no exception.

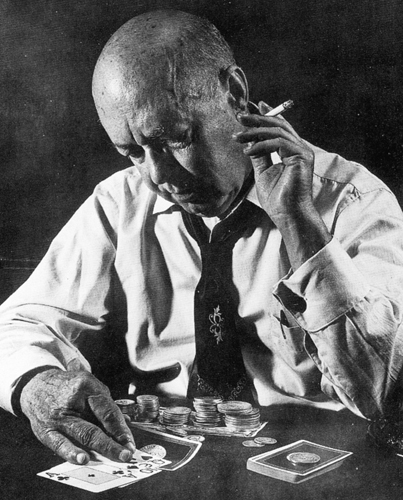

Yardley's role in the development of American codebreaking is an interesting and vital story. Yardley, who was the source of much of today's intelligence apparatus, was quite a character in the annals of cryptology. He was many things to many people, but above all he was a natural and inspired cryptanalyst in the days of pencil-and-paper cipher and code systems. Kahn's account is the first to show Yardley as a living, breathing person with all the faults that come with humanness.

The book discusses at length Yardley's connections with William Friedman, the U.S. Army's leading cryptanalyst. Many details of their interaction are disclosed here for the first time.

Both Friedman and Yardley were eventually left behind when cipher machines (such as the German Enigma, the British TYPEX, and the American SIGABA) emerged after World War I, because the technology needed to solve the ciphers created by the machines was far beyond what either man could envision. Although Yardley was not much interested in the solution of such ciphers, he did recommend their use on occasion. Friedman, on the other hand, seems to have become somewhat embittered about the entire subject, even though he himself had developed some of the foundational tools used for the cryptanalysis of machine ciphers. He became an administrator, and Yardley turned to a bewildering variety of pursuits in order to earn a living.

Yardley's sensational 1931 memoir, The American Black Chamber, was an exposé of the cryptanalytic trials and successes of American codebreaking as he knew it. The book, which reads like a suspense novel, introduced the public to the arcane subject of cryptanalysis and the sometimes nefarious means used to do it. Kahn gives us many details about the book's publication and its effects on the country, such as the debate that ensued about the appropriateness of broadcasting what had been secret information. This is all quite interesting reading, from which many lessons can be drawn.

For all his likability, talent, charm and genius, Yardley can be seen as a victim of himself. He never tried to play the game that is required of those who want to be movers and shakers in government circles. He probably could have done so successfully, but that kind of endeavor would have seemed boring and pointless to him. Yet we are fortunate that the world has Yardleys in it and authors like David Kahn to tell us about them.—Cipher A. Deavours, Mathematics and Computer Science, Kean University, Union, New Jersey

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.