This Article From Issue

November-December 1998

Volume 86, Number 6

DOI: 10.1511/1998.43.0

The Camel's Nose: Memoirs of a Curious Scientist. Knut Schmidt-Nielsen. 352 pp. The Island Press, 1998. $24.95.

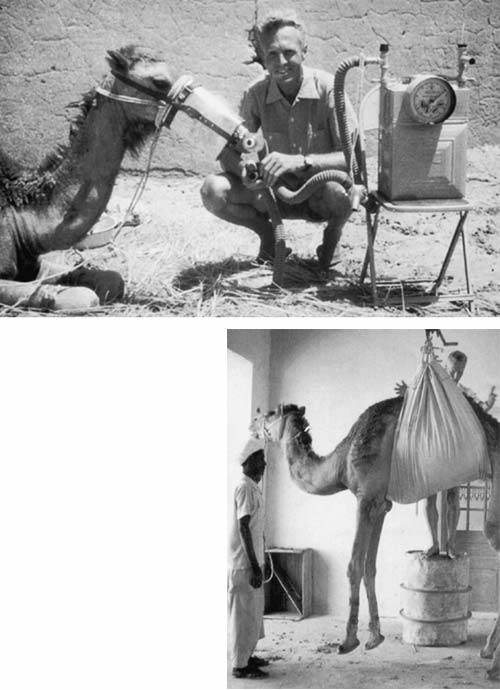

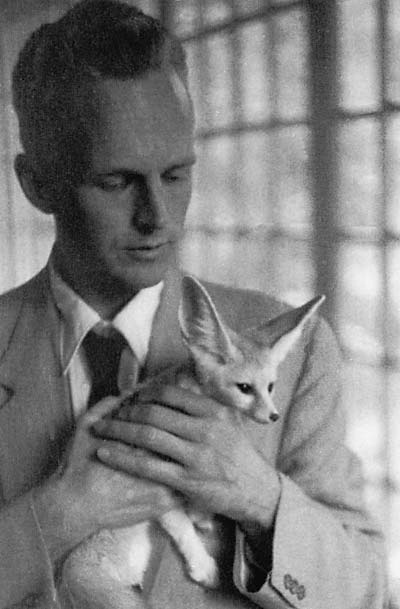

Knut Schmidt-Nielsen is one of the most influential comparative physiologists of our time. He won the International Prize for Biology, and his books include the now-classic text, Animal Physiology. I have used it when I have taught comparative physiology; it is the most useful reference for beginners interested in physiological problems encountered by marine-mammal biologists. Schmidt-Nielsen also is a teacher with very few peers. A single lecture of his can be more informative and worthwhile than an entire semester from most other professors. His research record is as impressive: No one is better at showing how complex but fundamental biological concepts work. A classic example is the camel's nose. By applying countercurrent-exchange principles to the mucus-lined tube that is a camel's nose, Schmidt-Nielson demonstrated how the animal, through the simple act of breathing, can save about 60 percent of the water that would have been lost from evaporation during respiration. This answered the age-old question of how a camel conserves water so that it may thrive in an environment where other animals would die of thirst. Perhaps more important, he has offered a generation of scientists the tools to gain insights into the first principles of life—simple, solid, understandable and useful connections between the math, physics and chemistry of living organisms.

Before I continue, I must inject a disclaimer: I am rather biased in favor of Schmidt-Nielsen. Much of my own work has been influenced by or touches on topics he has studied. I was a visiting scholar in his lab 15 years ago while on sabbatical at Duke University.

Schmidt-Nielsen prefaces The Camel's Nose by calling it "a personal story of a life spent in science." I would add that when one is with Schmidt-Nielsen, in person or in prose, one is immersed in science. The book helps explain some of the personality quirks I used to attribute to his being "European old school." Often scientists are pictured as unemotional, their decisions divorced from everyday problems. This dichotomy is false; real science is done by real people. In this autobiography, Schmidt-Nielsen describes the struggles throughout life with questions in personal and scientific endeavors that cannot be separated from one another.

The book is a delight—I can hear the author's voice when I read his words. There is considerable attention to food. This is consistent with the man; when one visited the Schmidt-Nielsens' for dinner, everything was planned to perfection, from fine wines from his extensive cellar, to exquisitely colorful and tasty food on a simple but beautiful table setting. Stimulating and memorable conversation before and after dinner was always part of the plan. Early in the book, KSN describes his mother's explanations of the physics of food and cooking in the kitchen. This passage triggered a memory of my helping wash dishes after dinner one evening. "Butch," he said, "the small change in temperature between here and your home in Maine has modified the viscosity of the soap sufficiently to allow you to misjudge the amount you are using." I was so embarrassed that I never wasted soap (in his house) again—after that, he never asked me to help with the dishes! His descriptions of the physics and chemistry of foods ranged from how chocolate is made and why it tastes the way it does to why salads with vinegar dressings shouldn't be served early in the meal if (good) wine is to be drunk. (Vinegar destroys the subtle aspects of the wine.) The Camel's Nose is filled with touches of humor and self-deprecation. Throughout, Schmidt-Nielsen makes it clear that short-term failure and insecurity are real parts of life—it is often a surprise to the young and inexperienced student that professors make mistakes or do not get funding every time, or that they don't know everything. During my sabbatical, Schmidt-Nielsen would often say "stop asking me questions the answers to which I do not know." Yet he knows more than any other person I have worked with and he is unafraid to say, "I do not know." The joy is that he helps you find out.

This book has for me filled in some of the missing pieces of a very complex human being. Once after he returned a piece of my less-than-elegant writing with a comment on poor writing in general, I tried to defend my ineptness (rather weakly) with, "Well, writing is easy for you but hard for me." He replied, "Writing is the single most difficult thing I do." That statement was one of the greatest shocks I had. It never occurred to me that KSN—whose clarity in writing was, I believed, unrivaled—struggled. He always insisted on clear and simple writing. In his book, he quotes Torkel Weis-Fogh: "Good science can be interesting, fun, and a pleasure to read." In this book, certain parts seem to be taken from field notes, others from the memories recalled at his well-worn writing desk. Writing may be difficult, but Schmidt-Nielsen makes reading easy.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.