The Real Twilight Zone

By Fenella Saunders

The term has scientific roots

May 11, 2015

Science Culture Sociology Technology

Besides being Richard Feynman’s birthday, May 11 marks National Twilight Zone Day. The establisher of the holiday, as well as the reason this date was chosen, is appropriately murky (it’s not the date the show first aired). We like to think that Feynman might have been amused by the association.

The term “twilight zone” didn’t originate with the show, as the show’s fan site The Twilight Zone Archives acknowledges:

The original phrase ‘twilight zone’ came from the early 1900s, used to describe a distinct condition between fantasy and reality. The phrase then evolved into a term used to define the lowest level of the ocean that light can reach, and then as an aeronautical term used by the U.S. Air Force. When Rod Serling was asked how he came up with the title The Twilight Zone, he replied, ‘I thought I’d made it up, but I’ve heard since that there is an Air Force term relating to a moment when a plane is coming down on approach and it cannot see the horizon. It’s called the twilight zone, but it’s an obscure term which I had not heard before.’ Our guess is that Serling had likely heard the term before, but had forgotten it; this premise is based on two facts—his experiences as a paratrooper in World War II, and from his brother, Robert Serling, who worked as an aviation editor for United Press International.”

A 1999 Engineering column by Henry Petroski, “Daubert and Kumho,” which discusses the concept of expert witnesses, quotes a 1923 court case about the admissibility of novel scientific evidence (in this case, lie detector tests):

Just when a scientific principle or discovery crosses the line between the experimental and demonstrable stages is difficult to define. Somewhere in this twilight zone the evidential force of the principle must be recognized, and while courts will go a long way in admitting expert testimony deduced from a well-recognized scientific principle or discovery, the thing from which the deduction is made must be sufficiently established to have gained general acceptance in the particular field in which it belongs.”

In the July 1946 issue of American Scientist (long before the Twilight Zone show aired in 1959), Archibald Henderson of the University of North Carolina authored “Science and Art: An Approach to a New Synthesis.”

In it, he states:

A philosopher with a deep insight into mathematics and the process of scientific and philosophic thinking, John Dewey, in his Art and Experience, has beautifully clarified and illuminated that twilight zone of creativeness where both artists and scientists function. The fault lies in a literal, unperceptive psychology which cannot or does not distinguish modalities in imagination, or nuances in intuition. In both artists and scientists, Dewey rightly maintains, "there is emotionalized thinking, and there are feelings whose substance consists of appreciated meanings or ideas.”

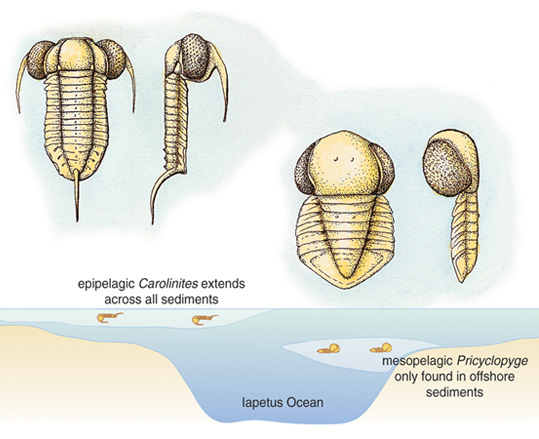

A 2004 article, “The Lifestyles of the Trilobites,” by Richard Fortey, returns to the original oceanography definition:

Some other strange, large-eyed trilobites may have lived at some depth in the water column rather than near the surface. Cyclopygid trilobites are bug-eyed forms that were generally wedded to a deep-water habitat, probably below 200 meters. They are often found in the company of blind trilobites that lived on the seafloor in deep waters, within sediments that accumulated at the edges of former continents or deep shelf sites. Studies of the eyes of these trilobites show that they are comparable to those of modern insects and crustaceans that live in dim light. So it seems likely that cyclopygids were animals of the mesopelagic region, the ‘twilight zone’ just below the ocean’s photic zone, and their remains accumulated in death alongside bottom-living trilobites that had lost their eyes. Curiously, a few of these deep-water pelagic animals had square lenses, rather than the more-typical hexagonal ones, for reasons that have yet to be explained.

Illustration by Emma Skurnick, adapted from McCormick and Fortey 1998.

In 2006, the show itself inspired comparison to a real but barely conceivable location: the radioactive region around the melted-down Chernobyl nuclear reactor. In “Growing Up with Chernobyl,” Robert Chesser and Robert Baker describe their research in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone:

Although the ‘Zone’ was now nearly deserted—more than 135,000 people had been evacuated from the region—we were amazed by the diversity of mammals living in the shadow of the ruined reactor only eight years after the meltdown. The odd juxtaposition was eerily reminiscent of one of the creepier Twilight Zone episodes.

Photograph courtesy of Robert Chesser and Robert J. Baker.

On a day that celebrates an iconic show that critically examined humanity, morals, and even sometimes modern technology, it seems fitting to look back at the term’s scientific roots—and then to close the circle by considering its role as a fitting descriptor of what could arguably be seen as one of humanity’s darkest technological episodes.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.