Seeing the Unseeable

By Peter Pesic

A new documentary film provides a fly-on-the-wall view of two recent endeavors to understand black holes: the work of the Event Horizon Telescope team to make the first picture of a black hole, and a theoretical initiative to resolve the black hole information paradox.

March 4, 2021

Science Culture Astronomy Physics Astrophysics Cosmology

BLACK HOLES: The Edge of All We Know. A film directed and produced by Peter Galison, edited and coproduced by Chyld King; in association with Sandbox Films. Distributed by Submarine Entertainment and available for streaming on Apple TV and other digital platforms through Video on Demand. Runtime 98 minutes. 2020.

Though dark and mysterious, black holes have become brilliant celebrities. The “chirp” of two colliding black holes entranced the world in 2016 after being detected the previous year by the LIGO Scientific Collaboration; the first picture of a black hole, created from data obtained by the Event Horizon Telescope, drew great attention in 2019. Now we have a feature-length film starring these enigmatic bodies, produced and directed by Peter Galison, an eminent historian of science whose meteoric career has included practically every honor in that field. He is currently Joseph Pellegrino University Professor at Harvard and was awarded a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship in 1997. He has doctorates both in physics and the history of science, and his involvement in physics research has helped inform his influential books about its history and philosophy. As if this were not enough, his long-standing interest in the connections between art and science has resulted in collaborations with distinguished visual artists such as William Kentridge and a notable series of feature-length documentary films, of which Black Holes: The Edge of All We Know is the fourth.

Galison decided to interweave three strands in the film—observation, theory, and philosophy. There are two main story lines: The efforts of the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration, involving more than 200 scientists, are presented alongside the contemporaneous work of four theorists—Sasha Haco, Stephen Hawking, Matthew Perry, and Andrew Strominger—who are developing a new idea about information and black holes. The result is a very high-quality film, whose deep immersion in its subject and outstanding visual sense put it far above most science documentaries. It provides a feast for the eyes from the outset: Its opening sequence passes through a quiet Mexican town, as the camera rides along with scientists making their way up a mountain to one of the eight radio telescopes in a worldwide network of instruments that, linked together, form the Event Horizon Telescope. This is a thoroughly engaging and enjoyable film.

Galison has made good use of his deep access as a participant-observer. He is listed as a coauthor on Event Horizon Telescope papers, though he does not appear or speak in the film, which does not mention his involvement in the collaboration. Only someone with such access could have filmed the behind-closed-doors work of the Event Horizon team members. Galison likewise filmed conversations among the theorists in ways that would scarcely have been possible for an outsider to their world. He thus gives us a “fly on the wall” view of these extraordinary endeavors. In this somewhat unusual ethnographic film, a well-known colleague captures the “tribes” of physicists, astronomers, and philosophers meeting in the observatories, grand English houses, and Cambridge offices that seem to be their natural habitats. It is particularly pleasing to witness the diversity of participants from around the world and hear their various reactions, and especially to see the large and important roles played by women throughout the film.

Galison’s previous films with Robb Moss (Secrecy and Containment) broke away from relying on “talking heads,” but Black Holes: The Edge of All We Know returns to this familiar documentary device, perhaps because of the large number of “heads.” Still, these are interesting individuals, beautifully lit and filmed. Among them, two take a central place: Sheperd Doeleman, the director of the Event Horizon project, and Strominger, a physics professor at Harvard who (with Doeleman, Galison, and others) cofounded that university’s Black Hole Initiative. Doeleman and Strominger each provide a narrative voice for their respective projects; in different ways, both are interesting personalities, articulate and engaging.

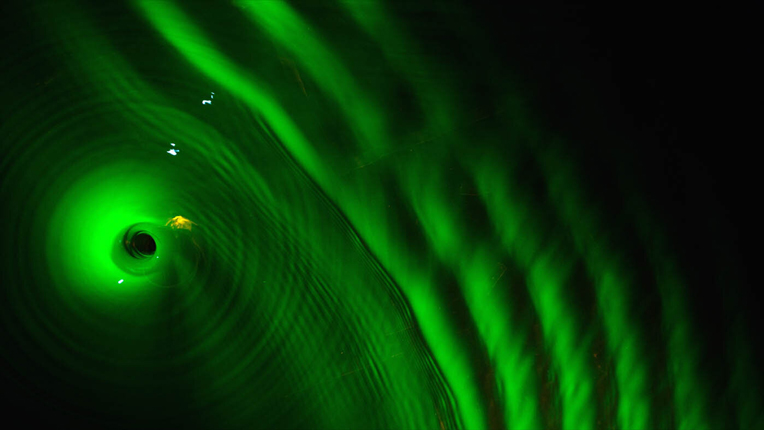

The black-and-white animations and graphic novel sequences in the film are particularly striking, interestingly coarse-grained to give a human feeling to phenomena so far from human experience. The animations illustrating cosmic distance scales—rather difficult to convey visually—were particularly neat and suggestive, using sharply etched grids that dilate and zoom. My favorite was the long, almost wordless sequence on the work of physicist Silke Weinfurtner, who creates spinning vortices in large tanks of fluid to mimic the behavior of black holes. These are visually ravishing: glistening whirlpools, vivid clouds of dye filtering through richly tinted fluids, glowing in a darkened laboratory.

From Black Hole: The Edge of All We Know.

Such sequences do a lot of work in trying to convey what might be the visual meaning of phenomena happening at vast distances and under extreme conditions; in effect, they are trying to see that which defies visualization. A great deal of the film shows the difficulties faced by the Event Horizon project—the huge problems of instrumentation, global coordination, and image extraction. We see something of the activity of four different teams, each independently tasked with making an image of the light from a black hole. To ensure objectivity, the four sets of results were only compared at the last stage. One wonders how those composite images were selected and assembled, how they looked at different stages. It would have been good to know more about how each team went about surmounting the immense difficulties involved in imaging a barely glowing, incredibly distant object. Did these extraordinary challenges require changing the nature of seeing itself? Or were the teams extending the use of established techniques?

It seemed harder for the film to show the work of the theorists, whom one sees making coffee, scribbling on blackboards, and talking over their difficulties. Even during the last months of his life, Steven Hawking continued to participate in their discussions; his collaborators speak of his importance and boldness. Unfortunately, what comes through here has more the aura of a star turn.

From Black Hole: The Edge of All We Know.

What is the information problem the theorists are trying to solve, and exactly why is it paradoxical? The film doesn’t make that clear. A few minutes are devoted to the subject, but an intelligent viewer might reasonably be puzzled and need more help. We hear about the laws of physics breaking down, about black holes being able to “spit out a piano” (whatever that means), even though their radiation seems random. All this is quite confusing. The underlying problem is neither clearly enough posed nor sufficiently elaborated for the viewer to really grasp it. As a result, we are impressed that these theorists work with thousands of algebraic terms (eventually needing the help of a computer), but we need more help understanding what to make of the “soft hair” their equations describe.

Of the three strands Galison envisioned for the film, observation is the one most adequately addressed, through the extensive coverage of the Event Horizon work. Theory, as I’ve just noted, seems less clear, because its questions don’t come sharply enough into focus. Philosophy seems the most neglected, even though we do hear from a few philosophers (identified as such onscreen). The film several times asserts that black holes are crucial for our understanding of the nature of space-time, even of the nature of physical law and of reality itself. But those claims, though provocative, need sustained explanation and discussion for them to enter the viewer’s mind as things to think about rather than merely admire from afar.

In the end, it was ambitious of Galison to try to do so much in one film with two big stories and three major strands. What we really need is a series of films of this high quality that could do greater justice to this material and build a larger story over the course of many episodes. Television has entered a renaissance through such series, which have become a powerful new genre in themselves. By comparison, a feature-length film is more like a short story or novel in its narrative range, and it inevitably struggles to accommodate something as ambitious in scope as what Galison attempts. Even so, he and his collaborators deserve much praise for having made a science film so far beyond the run of ordinary documentaries. Anyone who cares about science will find this film engrossing and rewarding.

As strong a medium as film can be for visual storytelling, it is perhaps less ideal for the presentation and discussion of complex intellectual problems. Galison has shown yet again that he is a master filmmaker. Is it too much to hope that he will now give us a more extensive treatment in a book, one that really lays out what he learned as a participant-observer and explores all the deep and fascinating issues of observation, theory, practice, and philosophy that lie beneath the surface of this film?

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.