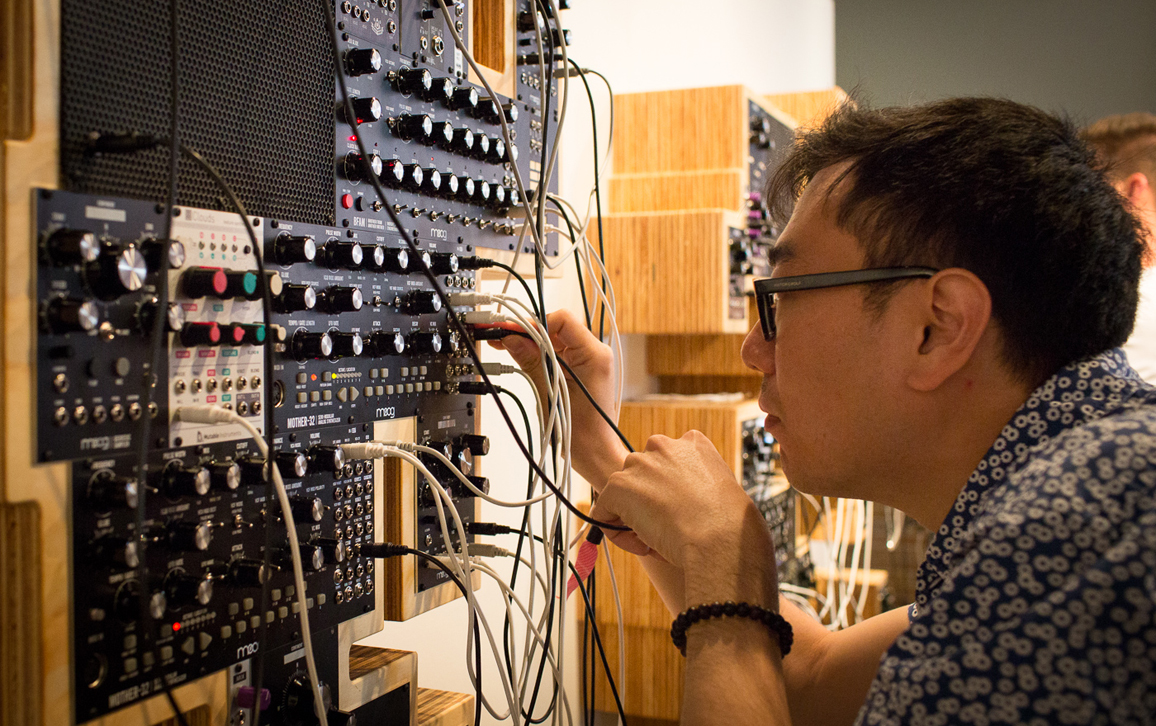

Moogfest Amps Up Connections between Science and Music

By Fenella Saunders

The music festival expands its technology track, for the benefit of both artists and scientists.

May 17, 2017

Science Culture Art Computer Technology

Moogfest, a long-standing music festival that celebrates the legacy of pioneering electronic musician Robert Moog, will take place in Durham, North Carolina, on May 18–21. This year’s lineup includes several scientists, who’ll speak on topics ranging from neurology to robotics. American Scientist executive editor Fenella Saunders discussed with Emmy Parker, Moogfest creative director and Moog Music brand director, why the festival is boosting its emphasis on science. (Incidentally, Parker, who describes herself as a science fan, has a family pedigree in music: Her uncle is Maceo Parker, best known for his work with James Brown.)

Tell us a little more about the history of Moogfest.

Moogfest started in 2004, when Bob Moog was still alive. The festival was a way for Bob to celebrate the music technology that he had created with the musicians who were using it. When Bob died suddenly the next year, the nature of the festival changed to celebrate Bob himself and his life’s work—the impact that it had, not only on musicians, but also on people who work across various disciplines, and of course within the sciences. Bob earned a physics PhD from Cornell University, and he’s responsible for defining the cutting edge of music technology in the 1960s and the 1970s. That’s what we’re paying tribute to at Moogfest. In doing that, we seek to bring together the innovators of today so that we can inspire the innovators of the future.

Electronic music has an obvious connection to technology. Moogfest has always had an undercurrent of discussion about technology as well, but it seems more expanded this year. Is there a reason for the timing of this upswing in programming about science and research?

The festival started in New York, we brought it back to Asheville in 2010, and then we moved to Durham in 2016. The upswing in science and technology programming is a natural progression of our move to this area because we have access and the ability to engage with the diverse research that’s happening in this area.

The intersection of science and art, of technology and music, is what our day-to-day work at Moog Music is focused on, and that’s certainly what Bob’s work was focused on. Moogfest is a reflection of our time, also. Science and research and evidence-based analysis and technology, exploring our natural world for answers—for us that’s what builds hope and faith in our future, and that’s what inspires human beings to explore what’s possible, what the limits of our creativity and our achievements are and how we can bust through those limits. For us, it’s not something that we intentionally seek to do; it’s who we are, it’s what our work is, and it’s what feeds us and inspires us every day, so it’s just us bringing that platform and that opportunity to people outside of the Moog factory.

Science and art have a long history of inspiring one another. Do you think that bringing in researchers will give them a creativity or collaboration boost from interacting with artists who might otherwise have remained outside of their sphere?

Creativity is most fertile when it’s inspired from multiple directions, not just from within one narrow field. We need to have collaborations and comparisons across disciplines to inspire new ideas, new forms. Without this kind of cross-cultural exchange, there’s some kind of limit that we’re imposing on art and on science. Whenever we put those ideas into a box, we’re doing ourselves—and the output and the potential—a disservice.

If you don’t perceive those limitations within yourself, you’re freer to create. It is distressing to think that there are people who sense these boundaries on a day-to-day basis, and if we have the ability to create an event that removes those boundaries for people, then that’s some kind of honor and privilege that we take very seriously.

I’ve talked to a lot of researchers about effective collaboration, and they often tell me that, although they can have really great collaborations with geographically distant colleagues, they need to have the interpersonal connection from an in-person meeting first. Can you talk about the potential for science-art crossovers that an in-person setting like this provides and how that can influence the way people collaborate?

There’s nothing that can replace human beings working together face-to-face to solve problems. I don’t think that even science can perfectly explain why human beings relate to one another through forms of deep listening, through empathic listening. When there’s authenticity and a sincere desire to connect on a meaningful level, it is fantastic what can happen, and that’s literally what we are trying to create for people.

How do you think discussions of research can influence the creativity of musicians and other artists?

People naturally synthesize their influences and reflect their experiences—and just like scientists draw inspiration from art and philosophy to be able to see their work and their research in new ways, artists in every medium naturally tend to incorporate new perspectives and ideas into their work. So when we expose artists to cutting-edge research, that expands what’s possible. It is going to be inherently thought provoking, and new ideas will come from it.

Do you think that, by bringing more science into an artistic festival, you can increase the audience for science while also enhancing the understandability of the research? Is there a humanizing element to showing science in a creative context?

I don’t know how you can disconnect science from humanity. Science is human. It’s human beings that have defined it, that expand it, that discover it, that do the research and then communicate it back. There is no separation between science and our culture. There is no separation between science and humanity, and so there are many different ways to explore and discover a myriad of topics.

Art and music can seem inaccessible to people as well—but ultimately, music is the great unifier. We do use music as this really wild, beautiful, diverse pillow for people to rest in while we also expose them to new technologies and to scientific research that ultimately will change the way they live their day-to-day lives. There are ways of allowing people to see how deeply connected they are, not only to the science, but also to those who are doing the research, as well as how much they have in common with one another.

I think that’s an issue we’re facing in every element of our culture right now: how we create these platforms where people can sit and talk to one another, listen to one another, so that we can discover that we have more in common than we thought.

We often find ourselves facing these false dividing lines between science and culture, where science is seen as something outside the norm of everyday life, unrecognized as underlying most things we do. The festival website emphasizes futurism, but what does it mean to be a futurist? Do you think being a futurist, in part, means healing that rift?

Ultimately, you can’t discover the future without sincerely engaging with what’s happening today. If you turn on the news, read a newspaper, have a conversation at the water cooler at work, or go onto social media, there are lots of opinions that are being expressed. Every decision, every conversation, everything we’re doing right now, today, is literally what’s going to define the future. If we are not able to create these platforms that allow us to communicate more freely with one another in an authentic way so that we can face these conversations with a level of compassion, it’s going to have a profound effect on the future that we’re designing for our kids.

I think we have to bring back the future as an idea we see as hopeful, as something that will be bright and equitable for everyone. To me, if we say that being a futurist is only focused on science, only focused on technology, that’s missing 99 percent of what the future will hold. It’s important for us to look at these things holistically.

Here are some notable science talks at Moogfest:

Andy Cavatorta of the MIT Media Lab discusses machine learning

Miguel Nicolelis of Duke University discusses research on brain-machine interfaces

Kate Shaw of CERN and her colleagues give a virtual tour of the Large Hadron Collider

Charlie Gersbach of Duke University discusses genome editing

Michael Clamann of Duke University discusses autonomous vehicles

See more at the Moogfest schedule page. Some of the talks will be livestreamed as well.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.