A Digital Menagerie from The Paper Zoo

By Dianne Timblin

A sampler of zoological drawings from Charlotte Sleigh’s book The Paper Zoo: 500 Years of Animals in Art, which we recently reviewed.

March 8, 2017

Science Culture Biology Communications Zoology

In her book The Paper Zoo: 500 Years of Animals in Art (our review), Charlotte Sleigh explains that back when European natural scientists were just getting their footing, opportunities to view animals endemic to faraway ecosystems were scant.

Social standing permitting, a natural scientist could cultivate a friendship with an aristocrat who maintained a personal menagerie. Or, funds allowing, they could embark on a costly and potentially dangerous journey overseas. Among those naturalists who chose to set sail for the specific purpose of scientific investigation was Maria Sibylla Merian (discussed below), who in 1699 received permission to go to Suriname to study the insects of the region.

A far more practical, although not inexpensive, option was to collect zoological drawings, gathering what Sleigh calls a paper zoo. For most with an interest in zoology it was the only reasonable option, at least until zoological gardens began to appear in the early 1800s.

One plucky scholar, Sleigh tells us, argued that assembling a paper zoo was actually preferable to visiting a menagerie housing living creatures. Conrad Gesner, a 16th-century Swiss naturalist, had this to say about the merits of two-dimensional fauna: “Princes of the Roman Empire used to exhibit exotic animals in order to overwhelm and conquer the minds of the populace, but those animals could be seen or inspected only for a short time while the shows lasted; in contrast, the pictures in [this book can] be seen whenever and forever, without effort or danger.”

In that spirit, we offer a selection of images from The Paper Zoo that may be viewed and enjoyed with utmost safety. Given the digital format, the risk of incurring so much as a paper cut is delightfully remote.

Friends in High Places

Purple-bellied Lory (Lorius hypoinochrous). Original watercolor, later engraved as plate 170 in A Natural History of Uncommon Birds, and of Some Other Rare and Undescribed Animals, by George Edwards, London, 1743–51.

All images from The Paper Zoo, by Charlotte Sleigh, 2017. Image courtesy of University of Chicago Press.

A member of the parrot family endemic to Papua New Guinea, the purple-bellied lory has a raspy, nasal cry that cuts through its forested habitat. The specimen shown in this watercolor by George Edwards is probably not taking a culinary interest in its dragonfly companion: Purple-bellied lories feed on flower nectar as well as several kinds of fruit.

As author Charlotte Sleigh explains it, Edwards, a seminal figure in natural history and ornithology, had the freedom to pursue this work thanks to “his powerful patron, the collector Hans Sloane, who secured for him an undemanding job at the Royal College of Physicians.”

Mistaken Morphologies

Dodo (“Didus”). Richard Owen, Memoir of the Dodo, London, 1866.

The popular image of the dodo as a plump, cartoonishly shaped animal derives largely from an influential Roelant Savery painting from the late 1620s. Over the centuries, there has been much debate about what the birds actually looked like in the wild: Captive dodos were likely overfed, and stuffed specimens may not have been proportionally accurate. The conversation continued in 2016 with the publication of an article in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology that takes on the question of morphology, aiming to present “novel and comprehensive information on the dodo and its anatomy” and “facilitate further scientific inquiry into the dodo’s form, function, and paleobiology, because after more than 300 years since this emblematic bird’s extinction, these issues still continue to stimulate heated debate.”

Of the Richard Owens image seen here, Sleigh says, “Founder of the Natural History Museum (as it is known today), Owen used underhand means to make sure that he acquired the first complete dodo remains to be recovered after the bird’s extinction at the end of the 17th century. His Memoir came out the following year, featuring this illustration of a squat, ridiculous bird—not unlike [John] Tenniel’s illustration of 1865 for Alice in Wonderland.”

A Paper Tapir

Young Sumatran tapir. Probably by J. Briois, March 1824. Gouache on paper. From an album of 51 zoological drawings made at Bencoolen, Sumatra, for Sir Stamford Raffles.

Young tapirs exhibit spotted patterns that help camouflage them in forested environments; they lose these distinctive spots about halfway through their first year. Sleigh explains that in addition to procuring the fine paper specimen seen here, Sir Stamford Raffles involved himself in what was at the time a novel kind of zoological enterprise: “Besides collecting this paper zoo, Raffles helped to establish the Zoological Society of London and its Zoological Gardens (now London Zoo).”

Legends of the Fall

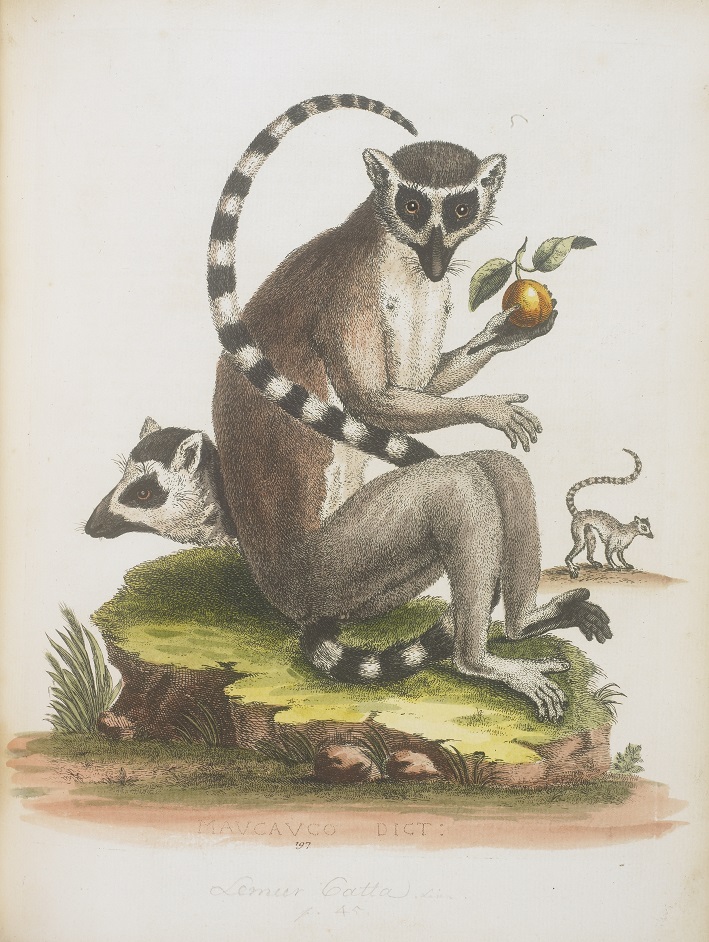

Ring-tailed lemur. George Edwards, A Natural History of Uncommon Birds, and of Some Other Rare and Undescribed Animals, London, 1743–51.

Ring-tailed lemurs form larger social groups than other lemur species, a condition that seems to help them outperform the others when it comes to sophisticated social-cognitive tasks such as subterfuge. Thus, at least among lemurs, they seem an especially apt analog for an artist wishing to allude to human behavior, as seen in this 18th-century work. Sleigh points out how its composition summons previous artists’ depictions of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden: “This picture summons up the myth of the Fall: the contemplated fruit, the lurking partner, the curling, striped, snake-like tail. . . . Edwards kept a ‘Maucauco’ (as the lemur was also known) alive for a while in his home, finding it a ‘very innocent, harmless Creature, having nothing of the Cunning or Malice of the Monkey-Kind.’”

“No Small Resemblance to the Bear”

Koalas. Watercolor by unknown artist; from the Marquess Wellesley Collection of Natural History Drawings.

Koalas have an ancient evolutionary lineage, dating back some 30 million years, according to Australian zoologist Stephen Jackson, author of the book Koala: Origins of an Icon. He remarks that today’s koala is, nonetheless, “the only surviving member of its family and has evolved into a specialized tree-dweller that feeds almost exclusively on the leaves of various species of Eucalyptus.”

Despite the social scene depicted here, koalas tend to be solitary by nature. But at the time this illustration was made, koalas were still relatively new to European naturalists, and there was much to learn. Of early scholarly discussion of the species, Sleigh says that “a report in the Philosophical Transactions of 1808 announced a new creature, seen a few years previously and known locally in Australia as a koala wombat: ‘The ears are short, erect, and pointed; the eyes generally ruminating, sometimes fiery and menacing; it bears no small resemblance to the bear in the forepart of its body.’”

Shell-Bent

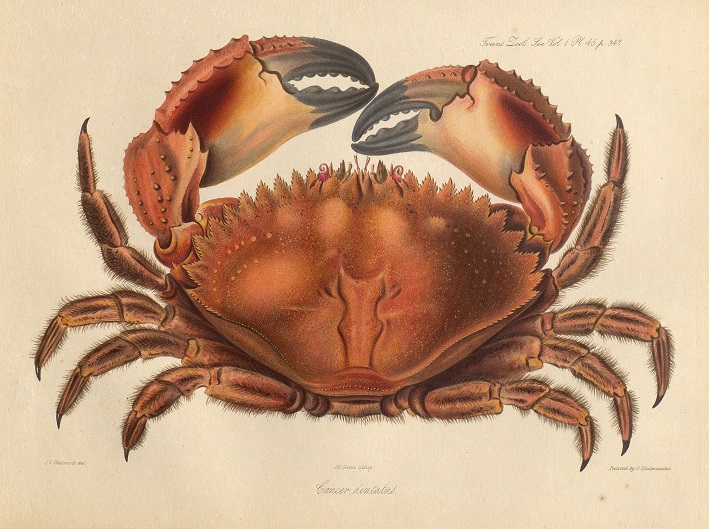

Crab (“Cancer dentatus”). Published in “Observations on the Genus Cancer of Dr. Leach with Descriptions of Three New Species,” by Thomas Bell, from Transactions of the Zoological Society, London, 1835.

Dental surgeon, naturalist, and zoologist Thomas Bell had a keen interest in shelled animals. Sleigh says that “Bell devoted his life to some of nature’s less glamorous creatures, amongst them the Crustacea. In his History of the British Stalk-Eyed Crustacea, he lamented that most works of natural history lacked all but the most superficial coverage of the class. This beautifully textured illustration of an exotic species helps to remedy that situation.”

Bell was also a pioneering researcher of turtles and tortoises. His book Monograph of the Testudinata, which also brims with stunning artwork, is believed to be the first such work dedicated to chelonians, reptiles enclosed within a double shell.

Of Insects and Winged Serpents

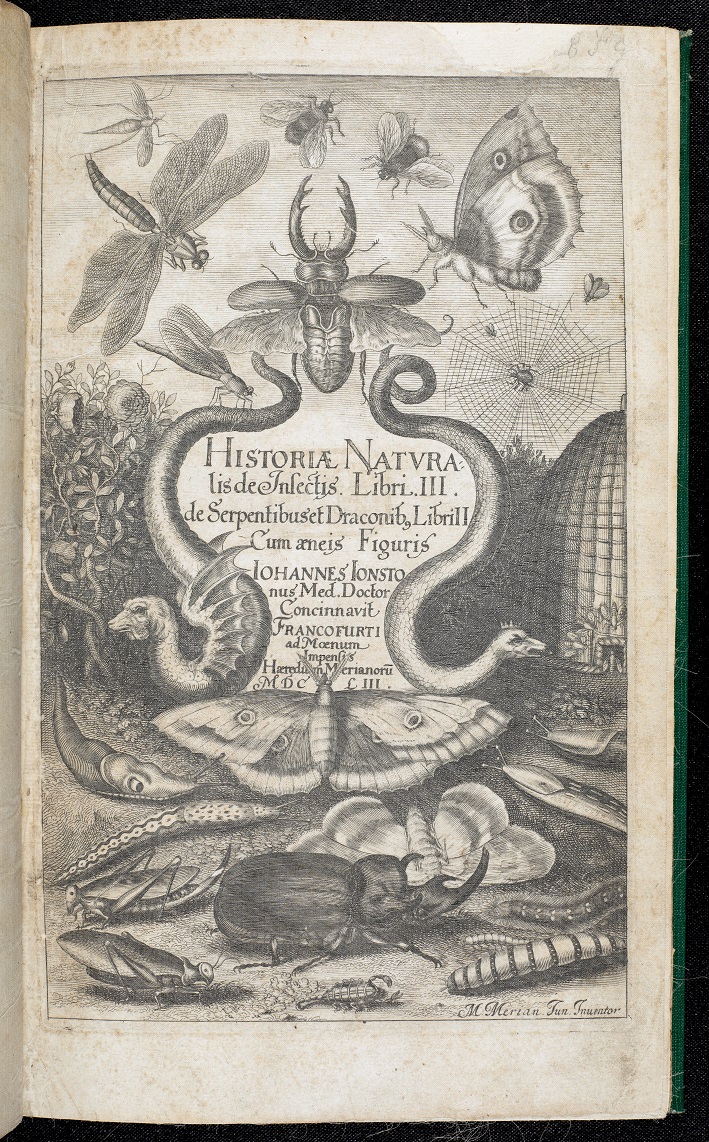

Historiae naturalis de insectis. Johannes Jonstonus, Frankfurt am Main, 1650–3. Illustrations by Matthäus Merian.

In the mid-17th century, speculative drawings were still an accepted practice, as evidenced here by the winged serpent depicted among a collection of creatures discussed in Jonstonus’s natural history of insects. Sleigh says, “The engraver and publisher Matthäus Merian the elder was the father of Maria Sibylla Merian, although he died when she was very young. He was apparently less committed to life-drawing than his daughter, producing visual descriptions of no fewer than eight separate species of unicorn.”

As for his daughter, her biological research and dedication to creating accurate scientific illustrations gained her a grant to travel to South America to conduct entomological studies. The book that resulted, one of many she authored and illustrated, was reprinted and revised to include updated entomological details in 2016. (Quite a few of her books may be viewed online.) Sleigh notes that “Maria Sibylla Merian is best known for her extraordinary insect drawings and her work on insect metamorphosis at the turn of the 18th century.” Sleigh designates her “the undisputed monarch of the insect artists.”

A Curlicued Cephalopod

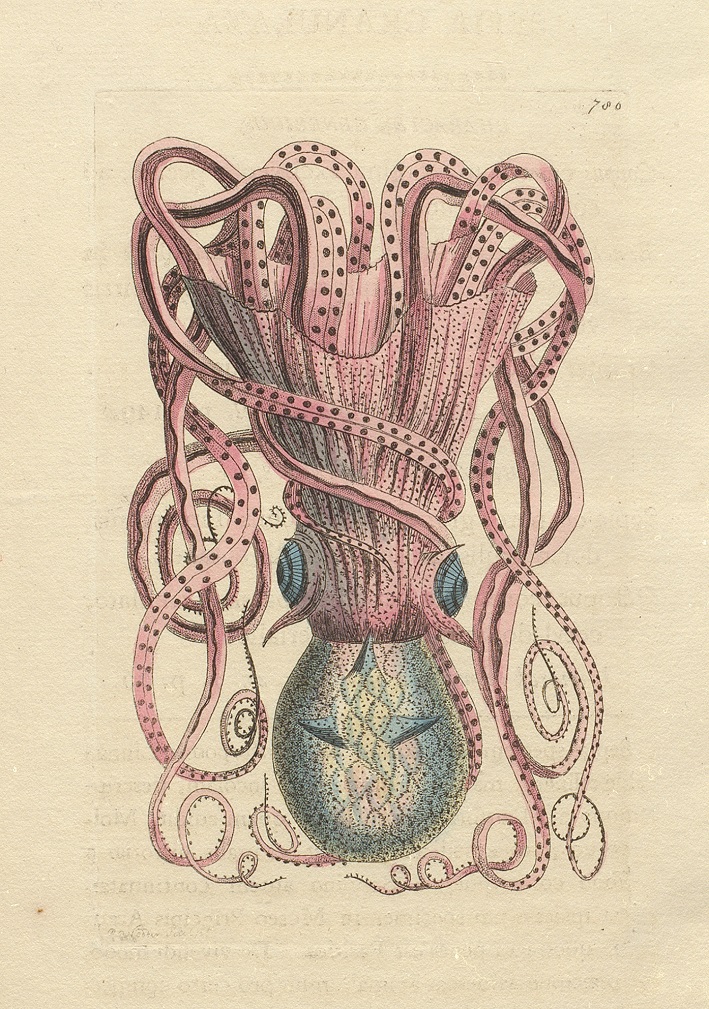

Octopus. George Shaw, The Naturalist’s Miscellany, London, 1789–1813.

The octopus, with its sinuousness, intelligence, agility, and apparent ability to shape-shift by adjusting its color and size, has held humans’ fascination for millennia. It appeared in Hawaiian and Samoan creation stories, for example, and the indigenous Ainu culture of present-day Japan included in its legends the octopuslike Akkorokamui, which was later incorporated into Shintoism as a minor spirit.

For some cultures, an aura of fear developed around the octopus, perhaps because of the creature’s elusiveness as well as the existence of such sizeable cephalopods as the North Pacific giant octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini)—the kind of improbable creature that quickly becomes the stuff of legends. Europeans’ phobias were further stoked by malacologist Pierre Dénys de Montfort’s 1801 drawing of a French ship under attack by a massive octopus.

Sleigh discusses Montfort’s influence on 19th-century cephalopod taxonomy and explains how the dangers of seafaring tended to affect zoological artists’ depictions of marine life: “The ocean is understandably a source of terror, and tales of giant squid or octopuses are one way of making such fears manifest. In 1802, the French naturalist Pierre Dénys de Montfort posited the existence of two such species. This example from a British book of the same era is truly the stuff of nightmares, coyly curled onto the page, but threatening to escape.”

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.