Rank Injustice: What Your Favorite Music Says About Inequality in Science

By Adam Shapiro

Processes that compile all-time best lists show how systemic bias emerges from seemingly fair choices.

January 18, 2022

Macroscope Ethics Policy Psychology Sociology

Everyone has favorite movies, TV shows, books, and music. That’s part of the appeal of “best of,” “top 10,” and “all-time great” lists. People feel like they can disagree about which are the 15 most important episodes of The Golden Girls, the best Beatles songs, or the greatest movies of all time without it becoming a matter of great moral consequence. Most would assume that things are different, more objective, or more sincere when it comes to ranking top scientists or the best research programs—the kind of evaluation that goes into determining funding awards and high-status prizes such as the Nobels.

Perhaps at the level of individual choices, ranking your favorite musicians doesn’t feel like it makes use of the same criteria as ranking the best scientific accomplishments. But aggregated into statistically significant samples, individual preferences add up to a stark reminder of what systemic bias looks like. Understanding how bias occurs and persists in one case may help shed light on the other.

From Kate Bush's Cloudbusting

I was reminded of this phenomenon during an end-of-year “all time”–style countdown this past December. Philadelphia public radio station WXPN spent a week playing selections from its member-voted list of the “2021 greatest albums of all time.” It was toward the end of that countdown, during the top 50 albums, that a statistically unlikely pattern occurred. For more than nine hours, a station that makes an explicit effort to promote musical diversity played music without any female vocalists (either as solo performers or as part of a band). This outcome was not likely to happen by chance. That nine hours represented 32 consecutive albums performed either by men as solo acts or by all-male bands (everything between Joni Mitchell’s Court & Spark at 43 and Carole King’s Tapestry at 10). That streak was just the most glaring example in a list that skewed overwhelmingly male, especially toward the top.

“Women have historically been underrepresented in the music industry in general, and I believe that has an impact on the connections people have made with music throughout their lives,” Kristen Kurtis told me. Kurtis, WXPN’s assistant music director and morning show DJ, responded by email to questions about the gender imbalance in the countdown. In part, she suggested, the results of the listener poll may be an artifact of generational bias and the smaller professional opportunities that many women musicians had during the 20th century. “We are a rock-based radio station, and women did not become more prevalent in the genre until the 1990s, so it's inevitable that they're going to continue to be underrepresented when you ask folks to pick their favorite albums of all time,” Kurtis said. WXPN’s list shares quite a lot in common with the most recent version of Rolling Stone’s Greatest Albums of All Time list, in which more than 80 percent of the top 50 are also exclusively male.

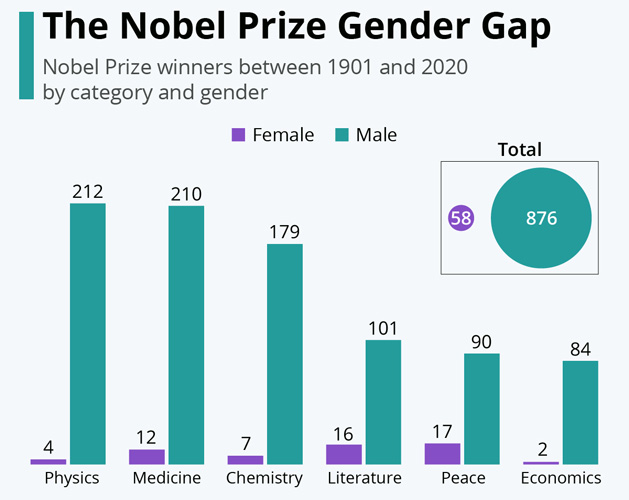

Similarly, in science fields women continue to be underrepresented, especially among the top echelons. Even though women make up a majority of undergraduate degrees in the United States, the National Center for Education Statistics states that men still receive nearly two thirds of degrees in STEM fields. That gender disparity is even wider for those at later career stages, as shown by census statistics about the STEM workforce.

The gender gap, both in STEM education and employment, has been shrinking over time. Is that shrinkage simply a matter of a gradual rise toward better equality from the ground up? I was somewhat surprised when Kurtis pointed me to arguments that the long persistence of inequality in musical tastes may be due to radio listeners’ brains. In a separate Twitter thread, she pointed to neuroscience research that Daniel Levitin wrote about in his 2006 book This Is Your Brain on Music, which suggests that individual music preferences are solidified between the ages of 13 and 25 because of the brain development that typically occurs around that age. Although WXPN did not ask for age or gender information from its listeners when collecting votes, Kurtis told me that this result from cognitive science may explain a generational preference toward certain bands and genres. “While I'm mainly talking about music that was NEW while you were 13–25, really, it's any music you fell in love with during that time which leaves an indelible mark on your brain, so younger people are still apt to emotionally connect with music older than they are, but older music fans are not as likely to become attached to music released after they turn 25,” Kurtis told me in our email exchange.

Does something similar happen in the sciences? Is there a particular age when our brains are most impressionable and open to embracing a STEM-focused career path? If so, do we have to wait to outlive the generation of Baby Boomers reliving the greatest hits from their own teenage wasteland? Generational turnover was once a popular explanation for how theories replace one another in the history of science too—an idea made popular by Thomas Kuhn back during the era of many of the rock anthems that dominated the top of WXPN’s countdown. More recent ethnographic and historical studies of scientific communities have painted a more complicated picture of how change comes about in science. But it seems that people are a lot more familiar or comfortable with Kuhn, perhaps in much the same way that the Beatles continue to be popular.

Regardless of whether a neurological or a social-cultural theory—or a combination of both—best explains why the 13–25 age range is when lifelong impressions have the strongest effect on us, Kurtis’s comments point to a deeper truth. The issue is not just generational skew but asymmetrical influence. Older generations continue to influence younger ones, but (mostly) not vice versa. Even though scientific communities are more open to inclusion (not only of women, but also of people in marginalized and underrepresented communities) than they were a few decades ago, older scientists and popular representations of science from earlier generations are still widespread and influential. It’s not the case that the top albums released since the 1990s suddenly show gender parity either. On the other hand, a top album poll NPR compiled of albums from just the past year was far more representative. (Kurtis also told me that a survey of the music of just the past year or the past decade among WXPN listeners would likely also have had greater parity.) But what we see in both music and science is damped generational turnover.

That generational lag may help explain why even if all barriers were removed, the scientific community wouldn’t experience representative diversity overnight. But on its own this lag doesn’t explain the outsized disparities when it comes to the most elite awards in STEM fields: The Nobels, the Fields Medals, and even somewhat STEM-adjacent awards such as the Pritzker prize for architecture or the Templeton Prize that rewards work in science and philosophy or religion. All these prestigious awards show overwhelming gender bias that cannot simply be explained by a lag because of past disparities.

The damped generational turnover skews the availability and roles of mentors and the efficacy of mentorship. Recent studies have shown that mentorship, “particularly same-gender and same-race mentoring,” in the sciences can encourage more underrepresented minorities and women in STEM to continue and succeed in STEM professions. Some of these studies suggest that the effects of mentorship mostly help in early career stages but have reduced impact further along. Similar phenomena occur in popular music, to the extent that it has been studied. A recent study of mentorship’s effects in electronic music concludes “that mentorship helps rising talents, but becoming an all-time star requires more.”

This also means fewer pathways to professional success that are not actively impeded by what a recent Nature Geoscience article called a “hostile obstacle course.” (Christie Bahlai has likened it to a “gauntlet” on this blog.) The obstacle course or gauntlet, rather than the commonly used “leaky pipeline” metaphor, illustrates the fact that many who reach levels of professional success do so against deliberate obstruction. Mentorship may play a role in helping early career scientists—and musicians!—navigate obstacle courses to achieve a greater degree of career security, but reaching that position often exacts an emotional and physical toll that affects one’s ability to become “an all-time star.”

There is evidence that this hostile workplace environment influences professional decisions that especially affect who is likely to reach the lofty heights of prestige associated with elite prizes. A 2019 Science Advances study showed that “topic choice” played a major role in the underperformance of African American scientists when it comes to winning grants. Research topics that scientists from marginalized backgrounds tend to pursue are either dismissed as niche and not impactful enough, or are advised against in favor of safer or more traditional approaches. Yet the U.S. National Science Foundation’s guidance explicitly states, “Program Officers are encouraged to recommend high-risk science and engineering projects for funding.” If underrepresented and marginalized groups are professionally discouraged from pursuing high-risk topics, then this guidance works against the goals of broadening participation in the sciences.

When female scientists do try a potentially high-risk novel approach, they are often afforded less professional leeway and security while doing so. Just consider the career trajectory of Katalin Karikó, whose work on mRNA vaccines has become world-changing in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, but whose career as an academic science researcher was derailed by its perceived lack of immediate utility. Although Karikó’s experience may eventually come to represent a plucky story of overcoming adversity to win a Nobel Prize, it’s clear that she faced more adversity than other Nobel Laureates, who retained academic positions with professional security. Historically, women’s achievements in these areas are also undervalued, perhaps because their research is seen as niche or unimportant—even when that research later proves foundational to someone else’s Nobel Prize.

In the music industry, similar problems exist when it comes to the risk-reward calculus. For the most part, male performers have greater autonomy and freedom to assume risk, to experiment and innovate, with the security of longer recording contracts and more assured radio play. It’s also not uncommon for women artists to be pigeonholed as performing in a niche genre that lacks universal appeal or to see their career derailed after a performance choice doesn’t lead to popular success.

Ultimately, the process resulting in recognition on lists such as WXPN’s raises questions about audience and purpose. When a single expert or a small group collaboratively curates a best-of list, they often do it to expose readers or listeners to new material that they may like. In a voter model such as the one WXPN used, the individual tendency to model inclusion on one’s ballot was washed out, and instead resulted in the predominance of the same old tunes. Kurtis and others at the WXPN knew that there would be gender bias in the results, she told me. However, she said that “senior managers felt strongly about being true to the voters and presenting the countdown the way the rankings shook out.” This decision may be presented as fidelity to voters and the idea that this practice represents a meritocratic process. But in part this attitude may indicate that the list is less a recognition of the artists who are being rewarded with inclusion and more of a celebration of the listeners themselves and applauding their musical taste and sophistication.

We might take that same conclusion and use it to consider: Who is the audience for the Nobel Prize selections? The limitations on who can nominate and vote on Nobel Prizes in the sciences points to the answer. The damping of generational turnover is virtually assured by the inclusion of past Nobel Laureates on the list of nominators. So who is the award for? Is it to send a message of value and recognition to the community of scientists worldwide? Or is it also a reflection of self-congratulation, a reassurance of the ongoing relevance and gatekeeping authority of an old guard operating under the pretense of meritocracy? It might be better for the sciences and for wider society if people started to view major prizes in this way. Nobel Prizes could be interpreted as sources of reputation and power in areas where power imbalances persist, rather than simply as objective recognition of achievement in a scientific field. Among nonscientists, Nobel Prizes have also become a proxy for nationalist and ethnic pride, and in some cases are invoked as justification for claims of intellectual and racial supremacy.

Perhaps the most important lesson that we might learn from comparing the ranking of scientists with that of musicians is that maybe those prizes shouldn’t be taken so seriously. Yet we continue to see their outsize influence, reinforcing an old guard’s gatekeeping and the disparities that go along with it.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.