Brooding Over Bees

By Marlo Chapman

Imported honeybee queens face disadvantages in new environments.

April 10, 2024

Macroscope

Courtesy of Leslie A. Holmes

Canadian winters are notoriously cold and harsh, and one Canadian resident, the honeybee, refuses to go outside at all during winter. Honeybees must store up food to survive the frigid months, but nonetheless, mass die-offs plague Canadian beekeepers every winter. Beekeepers must often replace their queen bees at the start of each season—sometimes up to half of their stock. But domestic beekeepers cannot provide enough queens to sustain the industry, and a common solution is to import replacements from warmer climates. Although these imports are essential, researchers have found that these queens and their colonies are less resilient than domestic ones. Reasons for this fragility are not limited to Canadian bees: Studying what makes bees successful or not in new environments could become more important as climate shifts and bees move to new areas.

The causes of a bee colony’s collapse are varied and intertwined. “When you dig deep enough, that’s a life history problem,” says Leslie A. Holmes, a postdoctoral researcher in ecology at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta. An organism’s life history includes how factors such as genetics, climate, predators, and disease can affect its growth and development—interactions that prove vital to understanding winter colony collapse.

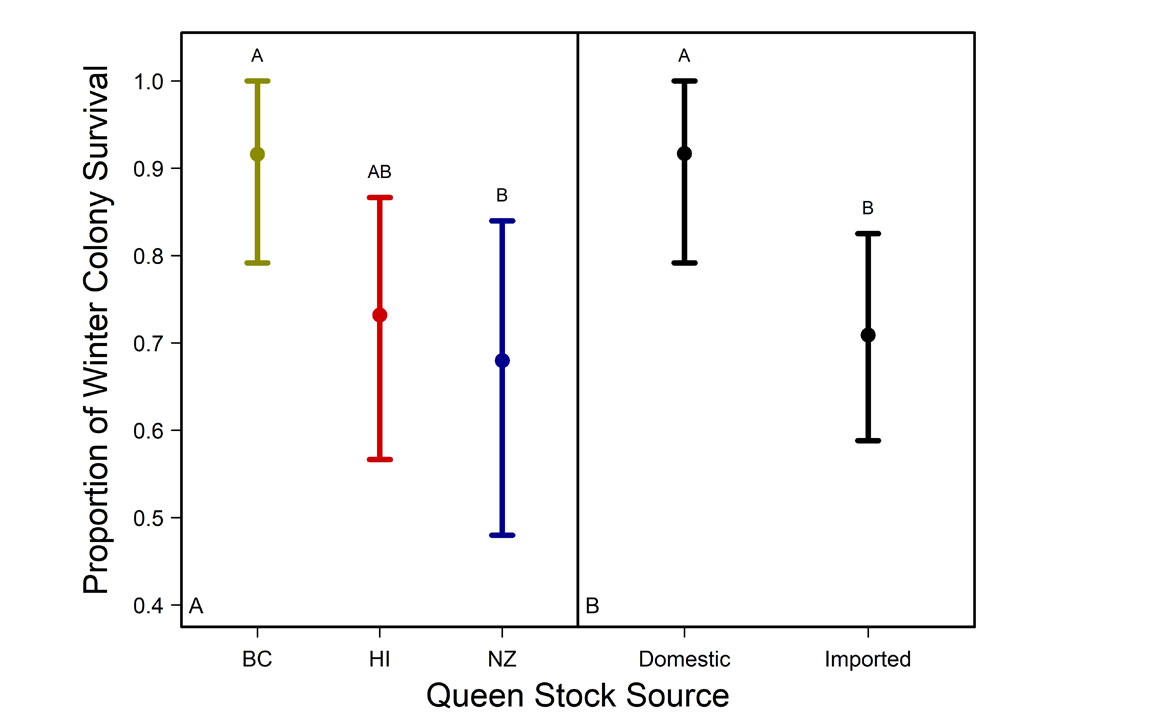

For more than two years, Holmes and her colleagues studied the physical characteristics, fertility, production, brood patterns, and winter survivability of imported and domestic Canadian honeybee queens. They found colonies led by domestic queens had a 25 percent greater likelihood of surviving Canadian winters.

Climate change could compound these issues. “We know temperatures are rising. We know we’re getting drier climates. And when you have bees foraging for water [instead of] nectar and pollen, then you’re potentially not going to have the stores needed for winter survival in the more temperate regions,” Holmes explained. Food sources would shift along with the new challenges of water scarcity. “You have climate change impacting the phenology [seasonal behavior] and natural ranges of different flower and insect species,” Holmes said.

A queen’s life history can impact a whole colony’s chance for survival. Colonies already have about a 20 percent chance of rejecting new queens, and genetic differences can further harm their chances of acceptance. Furthermore, imported queens are often mated before shipment, and their broods (eggs and larvae) may be genetically disadvantaged compared to domestic honeybees when it comes to immunity: A queen from the other side of the globe will not have the same resilience to local disease as a domestic queen. “So they’re already challenged before they even have to deal with the challenging environment, like harsh winter conditions,” Holmes said.

A queen imported in the spring that overcomes these challenges faces additional obstacles during their first colder winter. When temperatures drop below 10 degrees Celsius, honeybees will not leave the hive, and the close quarters for extended time makes colonies more vulnerable to disease. In this regard, bees are “just like humans,” Holmes said. “We are more likely to get sick in the winter because we’re all indoors, we’re all close together, we’re not out in the fresh air.”

Courtesy of Leslie A. Holmes

Holmes and her colleagues reported their findings on newly mated queens from New Zealand, Hawaii, and British Columbia in Scientific Reports in October 2023.

Researchers distributed bees among three sites in Alberta, with two sites near Lethbridge, close to the southernmost border, and another about 600 miles northwest, near Beaverlodge (55 degrees north latitude). The team gave each site a sample of queens from each country. The British Columbia bees were a mix of subspecies, and those from Hawaii and New Zealand were both Carniolan (a honeybee subspecies). Although they were the same species, there were notable differences between the two groups of Carniolan bees, with New Zealand bees having lower honey productivity rates and higher susceptibility to disease than those from Hawaii.

Courtesy of Leslie A. Holmes

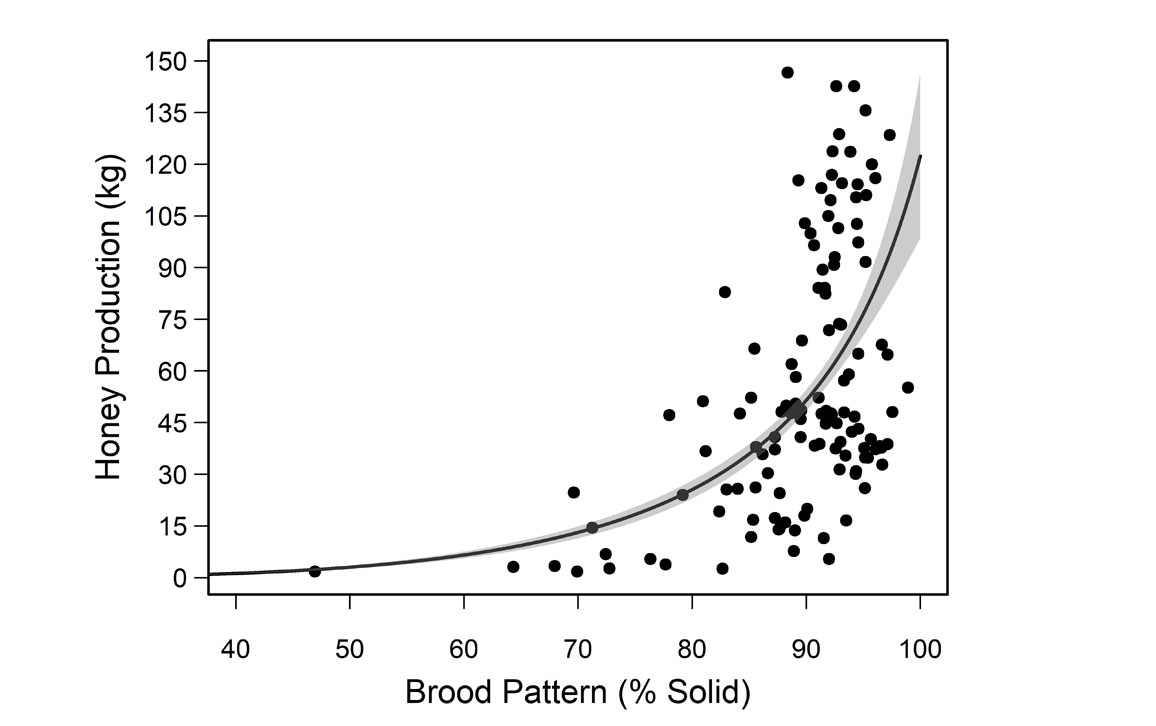

They also found that brood pattern solidness (the pattern in which a queen lays her eggs and the ratio of filled to empty cells in the colony) correlated with honey production: A more solid pattern meant higher honey output. Although some empty cells are expected, a pattern less than 85 percent solid is associated with lower honey production. Beekeepers use solidness as a quick way to assess the health and productivity of their queens.

The queen’s origin was a predictor for winter survival, quality of brood pattern, number of capped brood cells, adult bee populations, and the prevalence of a fungal disease called chalkbrood.

Courtesy of Leslie A. Holmes

The New Zealand queens performed poorly overall, and the team suspects that’s because of fungal chalkbrood, which affects them at much higher rates. They exhibited reduced brood patterns, higher rates of chalkbrood, and a 10-13 percent lower body weight than the other two queen stocks. Although chalkbrood is not considered as serious as some other bacterial diseases, such as ones called American or European foulbrood, it can still be detrimental to colony health. "We should not be ignoring chalkbrood,” Holmes said. “If you see chalkbrood, you should figure out what’s going on because it can just as easily destroy colonies.”

Courtesy of Leslie A. Holmes

Although they have become an indispensable part of the food industry in Canada and the United States, honeybees are not native to North America. They, too, were imported from Europe starting in the 17th century. According to the FDA, approximately one-third of the food eaten by Americans has been pollinated by honeybees, adding U.S. $15 billion to crop value.

Increased colony losses are not unique to Canada, nor is the practice of importing queen bees. Canadian beekeepers have reported high winter mortality rates over the last decade. U.S. beekeepers had their second-highest year of losses in the winter of 2022-2023. Most beekeepers reported losses exceeding the acceptable loss threshold of 20 percent by more than double, with an estimated 48 percent of colonies lost.

Courtesy of Leslie A. Holmes

Recent studies of competition between honeybees and native wild bees have also been a concern. But Holmes said findings from the Western Apicultural Society in Calgary showed that honeybees were not foraging the same pollen sources as native bees in Calgary, Alberta. Holmes said that makes it essential to find ways to help all the bees: “Honeybees are excellent pollinators of monoculture crops like canola and alfalfa, but all pollinators are so important for our food industry and food security.”

“I think the more we can understand the fundamentals of how these animals are interacting with their environment and one another, the more we can help these industries tackle the problems and challenges that they’re facing with climate change, and food shortage and security, to provide evidence-based science to inform policy,” Holmes said.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.