Answers to FAQs About the Coronavirus Pandemic

By Jessie Abbate

An infectious disease biologist is here to settle some common confusion about COVID-19.

March 26, 2020

Macroscope Biology Medicine Virology

Between scientists’ ever-changing understanding of the newly emerged coronavirus behind COVID-19 and over-interpretation of under-scrutinized reports, there's a lot of conflicting information out there. As an infectious disease biologist who studies the epidemiology of emerging pathogens such as Ebola virus, I've been fielding a lot of questions and am here to clear up some of the confusion.

1. Is it accurate to refer to this newly emerged virus as the “Chinese virus”?

In a word, No. This coronavirus has a name: SARS-CoV-2 (“sars cov two”), literally SARS version 2.0. Or, in a pinch, you can refer to it by the disease it causes (COronaVIrus Disease 2019, COVID-19). It jumped from bats to humans in China in 2019, but it could have done that anywhere in the world, much like rabies virus often does (for example, see this past American Scientist report). As the people who live along the Ebola River in the Democratic Republic of Congo know, calling a deadly pathogen by the location where it was found is unjustly stigmatizing, and can also be misleading (the Spanish flu, another name for the 1918 influenza pandemic, did not start in Spain). So naming viruses is no longer done that way. As far as we know, it’s not “novel” either, it’s just novel to humans.

2. Did the virus come from pangolins?

At this time, we do not know precisely how it jumped into humans, and it is still possible that an intermediate host was involved (but probably not snakes). The most similar viruses we know of are bat coronaviruses, but some parts of the genome closely resemble those from pangolins. The one thing we do know is that it was not constructed in a lab.

3. How easily does this virus spread?

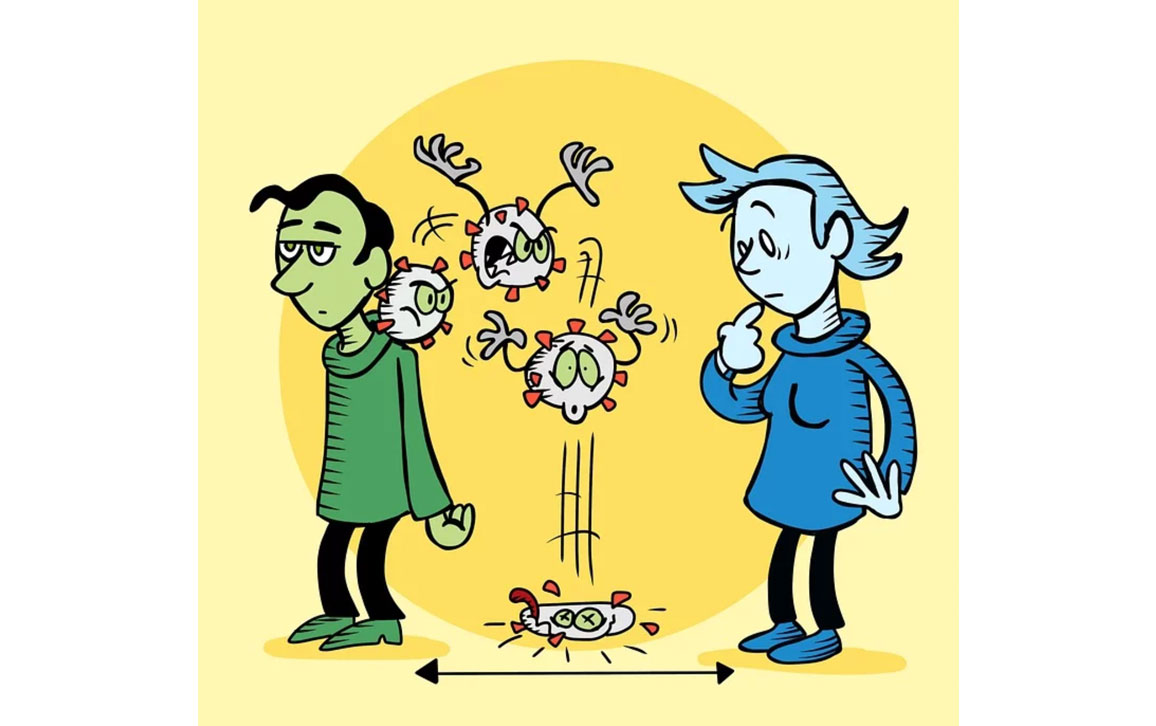

The most cited estimate is that each infected person transmits the disease, on average, to two to four other people before they recover (that’s its basic reproduction number). In a completely susceptible population, and with no interventions, this reproduction rate is similar to influenza. Although there is always some degree of immunity against most seasonal influenzas (dropping the flu’s effective reproduction number, meaning how many people can be infected by one sick person in a real-life population that has some immunity, to about one to two), there is almost certainly no such immunity against COVID-19. So essentially every person who is exposed is likely to become infected and transmit it. Exposure requires active virus finding its way, most likely through direct interaction with droplets from the respiratory tract of an infected person, into your respiratory tract—where the virus attaches and propagates. Viral particles are also shed from the digestive tract of infected persons, and can remain viable on some surfaces in the environment (and in aerosols produced by specific medical devices), but it is not clear to what extent these routes are responsible for transmission. It almost certainly is not able to transmit after a few days naked in the environment, despite reports of viral RNA being detectable for weeks. However, evidence is mounting that transmission can and does occur before symptoms begin, and also potentially from people who never develop any symptoms. Because people who don’t know they harbor the virus can transmit it to other people, social distancing is very important right now to reduce how quickly it spreads.

Wikimedia Commons/Siouxsie Wiles and Toby Morris/Spinoff.co.nz.

4. Is COVID-19 really more deadly than the flu?

In short, (1) we don’t really know yet, and (2) it will be much worse than the flu if we all get sick at the same time. In order to estimate the proportion of people who die from COVID-19—its case fatality rate—we must first be able to estimate the total number of cases. This estimation has proven difficult. Tests are limited in most places, less severe cases tend to go un-noticed, and so many of the parameters we typically use to estimate the true number remain in question (or may even be evolving). The number of people who die will also depend on quality and availability of supportive care. The percentage of severe cases requiring weeks of care in an intensive care unit bed (which could be on the order of 5–10 percent of cases) is more worrying than current estimates of the case fatality rate. Because everyone is essentially susceptible and we’re all being exposed at essentially the same time, the number of people with severe cases at any one time could be on par with the flu pandemic of 1918, which infected a third of the world’s population and killed an estimated 50 million by 1921. Where hospitals are stretched past their capacity, the case fatality rate will rise. Hard choices will be made to turn resources towards the cases with the highest probability of survival. The

best estimates we have at the moment come from China, where the case fatality rate was about 1 percent when both testing and care were more available (which is 10 times worse than seasonal flu) and as high as 12 percent when the system was overwhelmed.

5. Are we close to finding a treatment or vaccine?

A treatment? Maybe. A vaccine? Not yet. The World Health Organization has just launched a multinational study into repurposing four different treatments (currently used to treat other unrelated infectious diseases). Among these is the widely touted antimalarial drug, chloroquine. Although one initial study on its efficacy (also in combination with the antibiotic azithromycin) was certainly promising, there are a number of reasons to remain cautious: It was conducted on a very small number of patients, rushed through a questionable review process, did not have truly random control patients, and excluded patients who developed severe symptoms. In addition, a properly controlled Chinese study found no effect. As for a vaccine, there is one that has begun human trials (in Seattle, and soon in Atlanta), but the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Anthony Fauci, has been quoted as warning that mass deployment of a vaccine would not happen until human safety and efficacy studies had been completed, which should take 12 to 18 months.

Editor's note: Research about COVID-19 is developing quickly. Information included here is the best available knowledge on the date of publication and will not be updated in this post as the research evolves. We will continue to cover COVID-19 in future magazine content, and you can search on our site for our most recent coverage.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.