Birds, Art, and Interpersonal Drama Create a Compelling Story

By Freya McGregor

A new book explores how the work of John James Audubon helped shape our view of the natural world, alongside his complicated professional and personal legacy.

August 1, 2024

Science Culture Biology Ecology Review

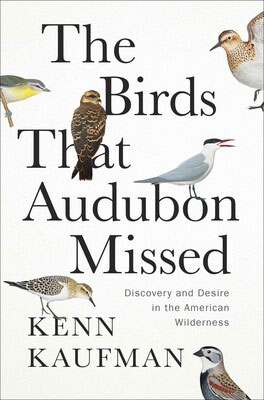

THE BIRDS THAT AUDUBON MISSED: Discovery and Desire in the American Wilderness. Kenn Kaufman. 400 pp. Avid Reader Press, 2024. $32.50.

Many North American nature lovers have heard of John James Audubon, the famous painter of birds who roamed the wilderness and discovered many of its mysteries. At least, that’s what he wanted us to believe. We are prone to creating heroes of people, and Audubon certainly helped craft that image of himself, but what was the reality? Did Audubon “discover” any of these bird species? What about all the Native Americans who knew them by other names? Was he as daring and intrepid as he wanted his would-be customers and admirers to believe? (Maybe.) Was he even what we would consider a birder today? (Doubtful. Birders these days don’t shoot birds to paint them—they enjoy birds by sight or sound without harming them.)

Kenn Kaufman, a well-respected author and illustrator of many bird and nature field guides, other bird-related books, and all-around bird lover, tackles the enigma surrounding Audubon in The Birds That Audubon Missed: Discovery and Desire in the American Wilderness. But he doesn’t limit himself just to Audubon: Kaufman also writes about various other naturalists who detailed bird species for Western science for the first time in the 1800s.

Instead of telling the story chronologically, Kaufman instead wonders about the various bird species that Audubon didn’t describe. Chapter titles include “A Thicket of Thrushes,” “The Fugitive Warblers,” and “Strangers on the Shore.” He ponders the possible explanations for why Snail Kites, Baird’s Sandpipers, Swainson’s Thrush, and other species were apparently overlooked—not just by Audubon, but also by Alexander Wilson and other explorers and ornithologists of the time.

The chapters are punctuated with "interludes" that are focused on art: a page or two describing Audubon’s techniques, or materials used for nature illustrations, paired with Kaufman’s expert analysis as he tries to paint all the birds that Audubon didn’t, in a style as similar as possible to Audubon’s. For readers with no art background, these interludes help to explain the skill Audubon had, as Kaufman narrates the artistic process and dilemmas of that effort. I found myself beginning to appreciate Audubon’s skill, if not his integrity, more and more as the book progressed.

However, Kaufman does not shy away from the darker realities of the oft-celebrated Audubon. He repeatedly calls out many inaccuracies in Audubon’s stories—John James consistently fabricated many of the legends about himself—and he delves into the morals and effects of Audubon enslaving up to nine people throughout his life.

Kaufman does not hide his feelings towards Audubon inventing new warbler species and naming them for wealthy potential subscribers to his The Birds of America. But true to Kaufman’s famed kindness and gentle nature in-person, his writing has only a hint of dislike—unlike the scathing writings that Audubon would publish about Alexander Wilson. With the push in the North American birding community to reconsider who we celebrate by naming organizations and birds for—and with the National Audubon Society deciding in March 2023 that they would keep their name—this book gives readers a deeper look into Audubon, leaving us to, perhaps, reconcile with ourselves whether any organization should bear his name or not.

Along similar lines, in November 2023, the American Ornithological Society announced it would change all the English eponymous names of birds in North America—those birds who were named after people. I have found that most birders don’t know who Gambel’s Quail or Bicknell’s Thrush were named after, although this doesn’t stop the naysayers claiming that this change “erases history.” Kaufman’s book faces this history and helps teach us about many of these less-than-stand-up folks.

My work is centered on making birding inclusive and accessible to people with disabilities, so it was interesting to read that recently, ornithologists making decisions about species’ classifications were reluctant to do so by sound alone. (It turns out bird species all make different noises, and there are plenty of pairs or groups of species that look almost identical and the only way to differentiate them in the field is by sound.) It’s fascinating how these biases flow down through time; indeed, the American Birding Association only changed their rules in 1992 for birders keeping their own lists of birds they have identified to allow 'heard-only' birds to be included. To this day, many sighted birders do not consider ‘heard-only’ birds as worthy of counting, compared to those birds they’ve seen, inherently dismissing the validity of blind birders’ experiences and completely excluding their contributions.

Photograph courtesy of Freya McGregor.

Although Kaufman doesn’t gloss over any of Audubon’s less-than-savory traits (such as enslaving humans, inventing birds—aka scientific fraud—or stealing other people’s glory and taking credit for their discoveries) anywhere in the book, it is not until the last part of the book that more in-depth discussion on the complex person he was takes place. Kaufman is honest and upfront, but also reasoned and compassionate, pushing against cancel culture and hunting for the inner beauty of this indefatigable lister. (A “lister” is a birder whose primary aim is acquiring a long list of all the birds they’ve identified in the wild.) He advocates for appreciating the art, even while removing the man who created it from hero status.

Wrapping up the account of how bird species are recognized by Western science, the final chapter will likely sound familiar to many North American birders. These days, instead of one person claiming discovery, comprehensive work on the part of many, often from multiple professional disciplines, results in species being "split" into two or more species, or "lumped" from two or more species into one single species. Reading about these "new" species that I remember being split—such as the Chihuahuan Meadowlark in 2022—fold us into the ongoing saga that Audubon, Wilson, and others were part of more than 150 years ago. Although the methods are incredibly different, this work isn’t done, dusted, and over. Kaufman would be the first to remind us, I think, that there is so much more about birds for us to seek and enjoy.

Although Audubon may not have been the upstanding citizen we would celebrate so highly were he alive today, Kaufman makes it clear that his art had a profound impact on the Western understanding of birds, as did the work of many of his contemporaries. Kaufman illuminates the work of these often under-acknowledged ornithologists, as well as the artistic skill Audubon employed. This book is written with a friendly, conversational tone, and the introduction to taxonomy means readers needn’t have studied biology to understand the rest of this book. The encompassing delight that Kaufman gets from birds is evident in many places, reminding even the most jaded birder that each experience we have with birds is a gift.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.