Most Popular Articles 2016

By The Editors

The most popular articles on our website over the year, 2016.

January 2, 2017

From The Staff Communications

In compiling a top-10 list of the year’s most popular articles on American Scientist, we decided to look at what you—our readers—have been searching for, not only among our most recent issues but in our archives as well. So here are the most popular articles on our website for 2016.

#10

A recent addition to the human family tree doesn't fit in clearly yet.

(July–August 2016 by John Hawks)

#9

Pulsed terawatt lasers create some surprising effects when shone through the air—including the channeling of light.

(March-April 2006 by Jérôme Kasparian)

#8

New evidence points to an alternative explanation for a civilization’s collapse. (September–October 2006 by Terry Hunt)

#7

Untangling this constant from Le Gran K could provide a new definition of the gram. (March–April 2007 by Ronald Fox and Theodore Hill)

#6

Few remember the man who discovered the “molecule of life” three-quarters of a century before Watson and Crick revealed its structure.

(July–August 2008 by Ralf Dahm)

#5

These ambling, eight-legged microscopic “bears of the moss” are cute, ubiquitous, all but indestructible, and a model organism for teaching science.

(September–October 2011 by William R. Miller)

#4

In space, flames don’t extinguish under the same low-oxygen conditions that would put them out on Earth, setting the stage for dangerous flare-ups.

(January–February 2016 by Indrek S. Wichman, Sandra L. Olson, Fletcher J. Miller, and Ashwin Hariharan)

#3

At one time or another, most of us have proved empirically, and painfully, the old mother’s tale that it’s possible to get sunburned on a cloudy day.

(May–June 2006 by David Schoonmaker)

#2

If the reader is to grasp what the writer means, the writer must understand what the reader needs.

(November–December 1990 by George Gopen and Judith Swan)

Update (January, 2018): This article was republished in 2008 in a "classics" section of our old website no longer available. The full feature is now available in The Long View blog.

#1

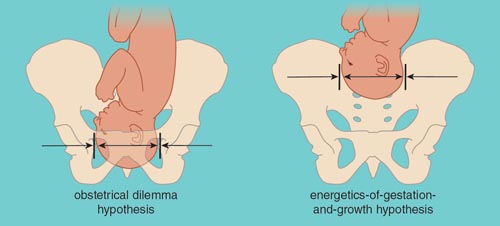

Having babies isn’t easy—and the standard explanation may be wrong.

(November–December 2013 by Pat Shipman)

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.