More Testing, Faster Testing

By Katie L. Burke

More types of tests for the coronavirus are becoming available, but how do we know which to use when?

October 12, 2020

From The Staff Medicine Virology

[Editor's Note: Updated information on COVID-19 testing is included in the Q&A with Michael Mina published in February 2021.]

Like most people in the United States, after seven months of pandemic times, I would really like to be able to go to public, indoor places without fearing that I’ll become infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. For that to happen, we need more testing and faster testing—and a strategy for finding and isolating presymptomatic and asymptomatic cases. But testing has lagged in the United States since the beginning of the pandemic. Researchers have estimated that we need 4.4 million daily tests in the United States to properly and proactively screen for the coronavirus. Right now, we have about 1 million daily tests, which are not equitably available throughout the country and which are mostly aimed at testing symptomatic people, even though up to 40 percent of cases may be asymptomatic.

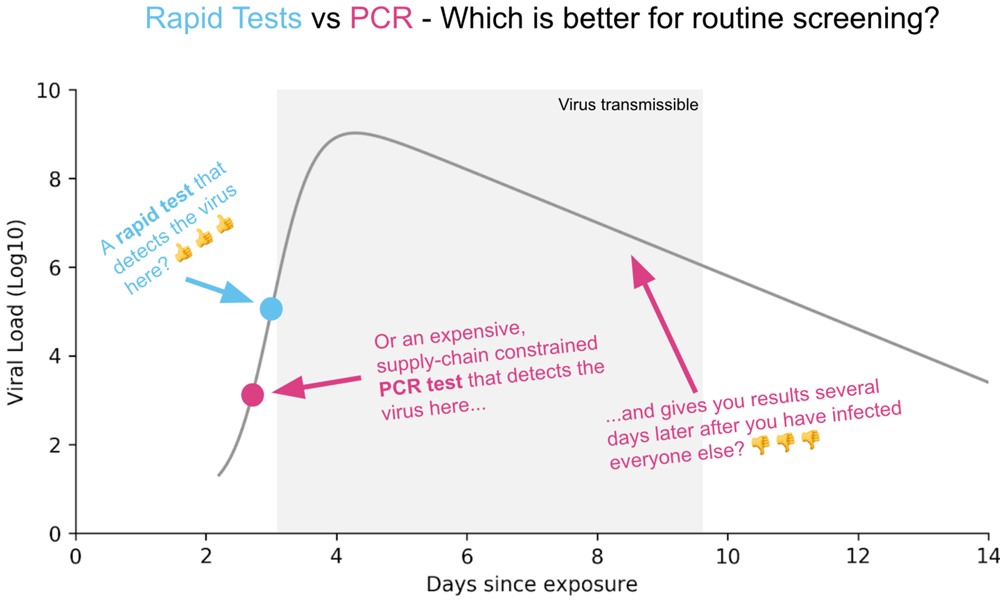

Figure courtesy of rapidtests.org.

There are two main categories of diagnostic test for SARS-CoV-2: PCR tests (short for Polymerase Chain Reaction, a lab process that copies the genetic contents of a sample to make it easier to detect their presence) and antigen tests, which detect particular viral proteins.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, PCR tests have been the gold standard, and odds are, if you go to a testing facility in your area, you’ll be given a PCR test right now. A PCR test may require a nasopharyngeal swab (the deep “eye-ball tickling” swab), a less deep nasal swab, or a saliva sample. PCR tests detect viral genetic material from SARS-CoV-2 in these samples, and they can detect the presence of the virus at a lower viral load than antigen tests. They are very accurate: False positives are close to nil, because you can only get a false positive through lab error. On the other hand, PCR tests could be overly sensitive, because they can detect the virus after a person has recovered and is not contagious.

PCR tests also take time, each sample requiring hours of staff time in a lab with expensive specialized equipment. Backlogs have not been uncommon. It has taken as much as two weeks to receive testing results—well after someone who tested positive would need to have isolated themselves to prevent spreading the virus. In my area, turnaround time has gotten better, and some labs guarantee results in 24 to 48 hours. I’ve even heard of people getting results within a few hours of their test. Still, accessible tests in minutes would be better, so people isolate as soon as they get results. Another downside of PCR tests is that they are inconvenient. You have to drive to a testing facility—and that driving time is not necessarily trivial in rural places. The inconvenience and slow turnaround time have prompted people to call for cheap rapid tests, which look for antigens, proteins associated with the virus.

There are different antigen tests in development as well as a few already on the market. There are two kinds of viral protein this type of test may detect: spike proteins (which stick out from the virus surface to bind to receptors) or nucleocapsids (part of the viral envelope). A PCR test amplifies the genetic material in a sample, so it can detect the virus at a low viral load. By contrast, an antigen test does not amplify any material in the sample, so a person must have a higher viral load for this type of test to detect an infection. The argument for using antigen tests for screening is that a person’s viral load may be highest when they are able to transmit the virus, so these tests can help prevent people who can spread the virus from entering public spaces. For rapid tests to be used community-wide screening—the type of testing most needed to drastically reduce the number of cases—these tests need to be fast, cheap, scalable, and sensitive enough to reliably detect people transmitting the virus.

Antigen tests from Quidel Corporation and Becton Dickenson & Company are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but they require proprietary equipment, which makes them more expensive and less scalable. However, Abbott’s BinaxNOW test, which detects nucleocapsids, does not require this specialized equipment, and it is one of the tests generating the most buzz after it was approved by the FDA in August. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services requested 150 million of these Abbott tests in late September, although epidemiologists have noted that that is nowhere near the number needed. Epidemiologist Jennifer Nuzzo of Johns Hopkins University told the New York Times on September 28 that this number of tests “is really a very small drop in the bucket.”

To take one of these Abbott antigen tests, you swab your nostrils and plug the swab into a credit-card–shaped repository, which will then give you a positive or negative reading within 15 minutes. This test has a positive test accuracy rate of 97.1 percent, and a negative test accuracy rate of 98.5 percent, at least when tested among known COVID-19 cases in the hospital. Although that is pretty good, it still means 1 to 2 people out of 100 could falsely test positive. So if someone tests positive, they would need to be tested again to confirm. In places where case numbers are low, any positive test would have a higher likelihood of being false. In places where the coronavirus’s prevalence is high (above about 5 percent), at a population level, most positive tests would be true positives. And although the false negative rate means that 2 or 3 people out of 100 might end up getting a pass when they actually could be transmitting the virus, that’s a much better scenario than the current situation. (Abbott's ID NOW rapid test has been in use for months and detects viral genetic material, but it has a higher false negative rate of 5 percent.) Nevertheless, the false negative rate must be taken into account when deciding on how to use this kind of testing: It only really works if you have enough tests to test people frequently. Right now, the Abbott ID NOW and BinaxNOW tests are only approved for testing symptomatic people within seven days of symptom-onset, and they must be administered in the presence of a trained healthcare professional. Using the test for what is most needed—community-wide testing of people without symptoms—is still considered off-label use.

Another antigen test to watch is the e25Bio paper tests, which detect spike proteins and look a lot like pregnancy tests. These paper tests would also be cheap, quick, and scalable, but their specificity and sensitivity are still being researched, and they have not yet been approved by the FDA. Some public health scientists have expressed frustration that the FDA continues to delay implementation of some of what they regard as the most effective strategies for testing and screening.

Figure courtesy of rapidtests.org.

The results of antigen tests are also difficult to include in state-level public health data, because, according to Rob Stein’s reporting for NPR and Neel V. Patel's reporting for MIT Technology Review, the places currently using them, such as nursing homes and universities, don’t efficiently transmit these data to public health departments.

For those who want to develop screening tests for their state or another particular population, this online calculator from Brown University School of Public Health and the Harvard Global Health Institute can help you decide how many tests you need. Stein of NPR recently reported on this calculator and presented a helpful infographic table on recommended testing numbers.

There are some other strategies for dealing with the slow turnaround times and lack of scalability of PCR tests—namely, testing wastewater with PCR tests or pooling samples of saliva for PCR tests to detect whether a group of people (say, a classroom of students or a university dormitory) has an infected person among them. But even this pooling strategy is not approved by the FDA for widespread use yet, and it is most effective when cases are rare. Pooled testing is being used in some places—for example, on some college campuses such as Duke University.

A few cautionary notes about testing: Daniel Griffin of Columbia University said in an August 30 episode of This Week in Virology, “People are often using testing improperly.” If you have a high-risk exposure, a negative test can give a false sense of security. A high-risk exposure is defined as being within six feet of someone who is infected, for more than 15 minutes. Griffin likens the absurdity of this sense of security to someone assuming they are not pregnant because they took a pregnancy test right after sex with a partner and got a negative result. They could still test positive later, after the pregnancy develops! A negative test result for SARS-CoV-2 right after a high-risk exposure does not mean that one couldn’t start transmitting the virus over the course of 14 days after that exposure. The only way to ensure one is not transmitting during those 14 days is quarantining, or testing negative daily, for that time period.

This problem would no longer be relevant if community-wide screening testing were implemented, and people transmitting the virus could be detected and prevented from spreading the disease as soon as they show up in public places. To do that, evidence points to an emphasis on testing frequency and rapidity over sensitivity. It looks like rapid antigen tests are going to have to be part of the solution, and we need clear guidelines to help dispel confusion and to implement them effectively.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.