How Much Sleep is Just Right?

By Sandra J. Ackerman

We’ve all heard warnings about the damage that too little sleep can inflict on immune resistance, blood pressure, and insulin sensitivity—to say nothing of mood. But what harm could possibly come from too much?

March 9, 2015

From The Staff Biology

What is a reasonable person to make of the study recently published in Neurology that appears to show getting more than eight hours of sleep per night is associated with a greater risk of stroke? We’ve all heard warnings about the damage that too little sleep can inflict on immune resistance, blood pressure, and insulin sensitivity—to say nothing of mood. But what harm could possibly come from too much? If only out of respect for the hour we sacrificed this past weekend, it’s worth considering the question.

A link between excessive sleep and cardiovascular events seems surprising at first, but the idea isn’t new to scientists who work at the nexus of neurology and public health. As far back as 2006, and again in 2009 and 2011, published studies were sketching out a U-shaped relationship in which the incidence of stroke is highest in two groups of people: those who tend to sleep less than five or six hours per night, and those who regularly sleep more than eight or nine hours. With other major risk factors accounted for—smoking, alcohol intake, age, and family history of stroke—the bottom part of the U, with fewest cardiovascular emergencies, covers the so-called “Goldilocks” cohort who get just the right amount of sleep: six to eight hours per night. (This two-hour range makes for a very broad category, as scientists in this field will readily admit; however, in order to be large enough to show anything significant, most of the relevant studies have had to rely on self-reports outside of a laboratory setting, so this broad-brush picture will have to do for the present.)

The new paper, published by researchers at the universities of Cambridge and Warwick in the UK, provides data on 9,692 men and women from the Norfolk regional subgroup of a well-known research population, the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer. Results of the 9.5-year prospective study of sleeping Brits echo earlier findings from China, Sweden, and Japan (second study here). Adults who are, to all appearances, healthy, but who sleep longer than about eight hours per night, are more likely to experience a stroke within the next decade than the population at large.

To be clear, no one is saying that giving in now and then to the appeal of an early evening or a lazy morning will produce a stroke. “We do not want to suggest causation—we are showing only a correlation,” says Yue Leng, first author of the Neurology paper. Rather than a cause-and-effect link, what’s likely is that a habit of long sleep itself develops as the marker of an increased risk, perhaps because of an underlying illness or disorder. Leng and her co-authors have also found that a shift from average to prolonged sleep is associated with a rise in the risk of stroke; in such cases, the onset of longer sleep may be a subtle cue that it’s time to schedule a medical checkup. Another point, offered by Alberto Ramos and James Gangwisch in an accompanying editorial, is that prolonged sleep often correlates with carotid atherosclerosis and left ventricular mass, both of which are potent risk factors for stroke. As framed in a recent review, the question of whether prolonged sleep is a “cause, consequence, or symptom” of illness will no doubt be with us for some time.

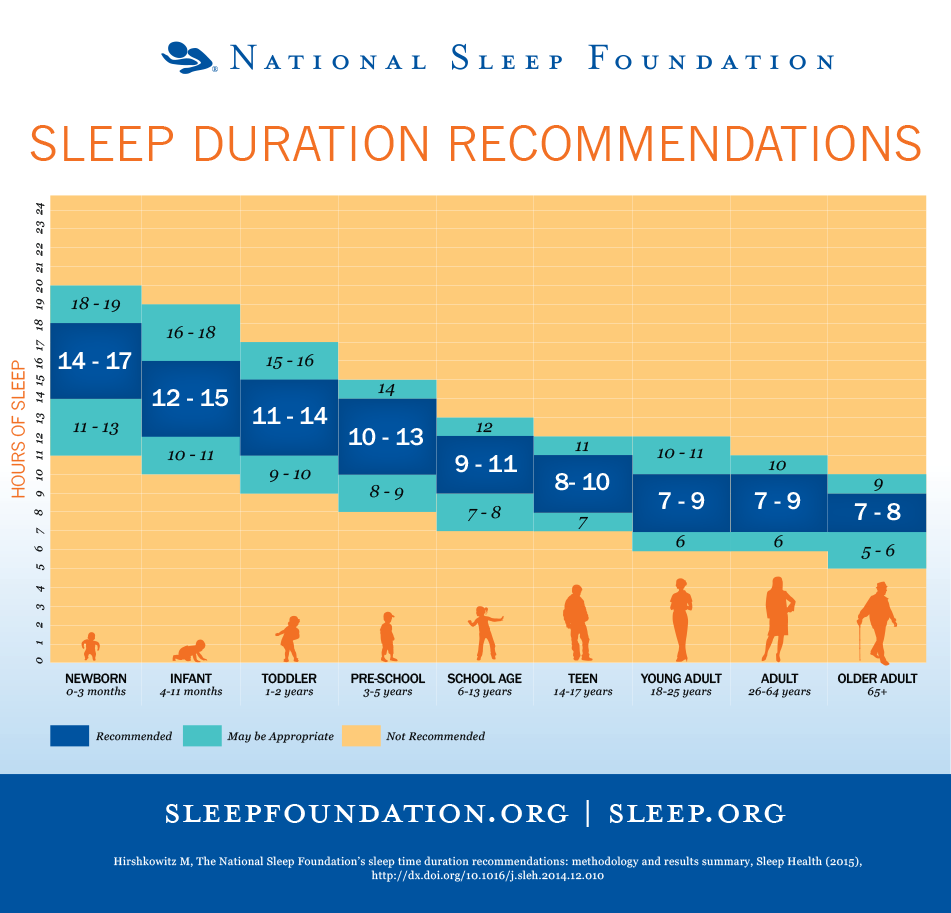

It’s important to keep in mind, too, that the British study found an association between long sleep and increased risk of stroke only in individuals aged 63 or older. “These were all healthy individuals at baseline,” says Leng, “but I don’t think that means our findings can be extended to younger people in their thirties and forties.” The need for sleep varies greatly with age, and, as it happens, the National Sleep Foundation has just come out with new guidelines on this very point.

In any case, as anyone knows who has ever sought repose in the vicinity of another human being, we are at least as individualized in our sleep patterns as we are when awake. And speaking of individual variation, what’s your own level of knowledge about sleep? You can find out with this quiz, courtesy of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

For now, while we struggle with those first few too-early mornings of Daylight Savings Time, we have our hands full trying to get just the right amount of sleep: not too little, and also (sigh) not too much.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.