Can Giraffes Get Stressed Too?

By Kayla Fulkerson

A human-based measure of health biomarkers can help animals housed in zoos.

July 5, 2024

From The Staff Biology Medicine Animal Behavior Physiology Zoology

Zoos serve as windows into faraway ecosystems teeming with life, where each exhibit transports visitors to different parts of the world. At Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium, for example, visitors can gaze over a sprawling habitat that mimics the African savannah. Here, they might see a herd of giraffes, seemingly content in their usual activities of eating and socializing. But beneath their seemingly placid demeanor, these animals might be hiding signs of stress. To help diagnose such a problem, researchers have discovered that a human-based measure, called the Allostatic Load Index or ALI for short, may play a pivotal role in assessing the well-being of iconic species such as the giraffe.

Image courtesy of Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium.

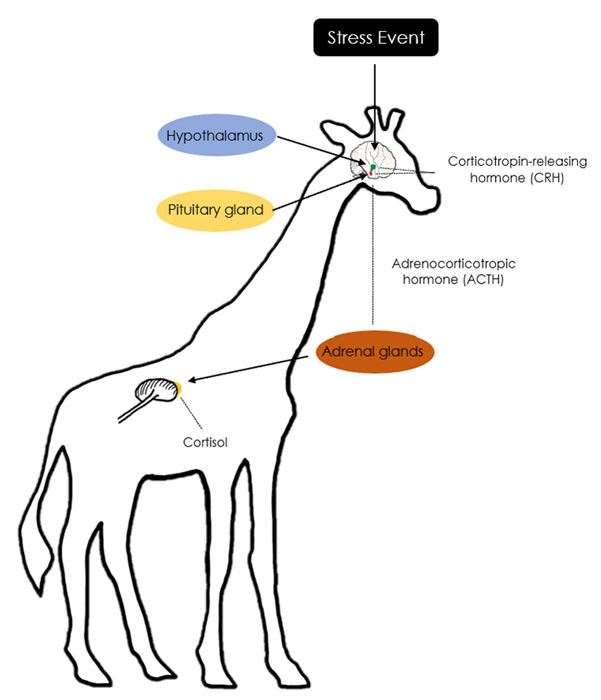

Allostasis refers to the body’s ability to maintain functional stability through change, specifically the stability of various physiological systems. Allostatic load, on the other hand, reflects the wear and tear of chronic stress on these systems. Researchers developed the ALI to assess how stress affects the overall well-being of a human by monitoring various health biomarkers. These biomarkers encompass different physiological systems, such as the cardiovascular, immune, metabolic, and neuroendocrine systems. In humans, examples of these biomarkers include blood pressure, levels of the stress hormone cortisol, and cholesterol concentrations. Researchers can use a slate of roughly 50 biomarkers to measure a human’s ALI accurately. But what biomarkers are most useful to measure the ALI of a giraffe?

Haley Beer, a postdoctoral researcher in animal sciences at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, and her colleagues investigated this question by examining blood serum from 18 giraffes at the Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium. Blood is regularly collected from the giraffes and stored frozen, and then recorded, along with other details about the circumstances of its collection, in an online database. For this project, the team was particularly interested in blood collected during various stress-inducing events.

“We had access to different blood samples, and we knew from literature about humans that knowing certain stressors is important,” Beer said. “We thought we could use this database to gauge how many stress events occur in captivity, such as being transported, illnesses, immobilizations, and pregnancies.”

Image courtesy of Josh Shandera/Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium.

The team sought to identify multiple biomarkers to discern patterns or deviations, rather than concentrating on spikes in individual biomarkers. This process is somewhat akin to analyzing a symphony orchestra's performance: Instead of fixating on one instrument's sudden volume increase, the researchers listen to the entire ensemble. This holistic approach enables them to detect differences in the overall harmony, making it easier to identify irregularities without overemphasizing changes in individual instruments.

The team chose five serum biomarkers and one physical marker of body condition that they hypothesized would fluctuate beyond their typical range as a result of stressful events.

These biomarkers have established associations between stress and physiological processes in humans and other animals, and they reflect hormonal changes, metabolic activity, and overall health. The researchers added a body condition score that included measures of well-being such as weight, muscle condition, and overall body health. This combination of biochemical and physical biomarkers allowed the team to assess both internal physiological changes and external indicators of stress.

After completing their analysis, Beer and her team found increased concentrations of two of the biomarkers, cortisol and fructosamine, when the giraffes experienced a stressful event. Cortisol is extensively used as a stress indicator, and the glucose-protein compound fructosamine is known to be released in response to insulin resistance that is induced by stress, so the elevated concentrations did not surprise Beer.

“Both of these are intuitive,” Beer explains. “The more stress an animal experiences, the more activation of the stress response, which involves the cortisol release, we will observe.”

By linking how humans react to increased biomarker concentrations and applying this knowledge to giraffes, cortisol and fructosamine emerge as promising additions to the analysis panel to help scientists measure the ALI in giraffes.

However, there were no observed correlations between stress events and two other biomarkers— cholesterol and a type of lipid called non-esterified fatty acids—as well as for body condition score. These factors are primarily affected by diet, and in zoos, meals are regularly scheduled and highly controlled. So these diet-managing practices may mitigate the potential effect of stress on these specific markers, or there may not be any physiological relationship between the markers to stress events in giraffes.

The research revealed that the overall ALI increased as giraffes experienced more stress events. The total number of stressful events had a more significant impact on ALI than the specific timing or nature of each stress event. Interestingly, the study found that neither age nor sex influenced the cumulative effects of stress.

“We were sort of surprised to see that the frequency of, or the time between, the events matter less than the overall accumulation,” says Beer. “Given that there was one animal that was two years old, and they had an ALI score of four.” She explained that the highest score the giraffes in this study could achieve was four, determined by the number of biomarkers used (which can vary across studies).

Additionally, the researchers found that the total ALI score did not correlate to one type of stress event more than another. However, they did find that some individual biomarkers corresponded more closely with specific stressors. For example, DHEA-S, a steroid hormone that counters the effects of cortisol, was linked to the stressful events of pregnancy and illness. When the body faces chronic stress and keeps making more cortisol, it can use up all of its reserves of DHEA-S, making it harder for the body to handle stress. Such a condition can lead to cognitive and reproductive issues and a weaker immune system. Beer and her team also saw that the ratio between cortisol and DHEA-S affected not only ALI and total stress events, but was also frequently observed during stress events such as illness and transport.

Image courtesy of Haley Beer/Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium.

“We know that DHEA-S concentrations are like a reservoir,” Beer explains. “It has these protective properties against negative physiological outcomes. So when you have more cortisol produced from being stressed over a long period, you will have lower concentrations of DHEA-S because it's trying to eat that up. You then have this reduced ability to cope with stress.”

Ultimately, Beer and her colleagues affirmed that ALI is a reliable measure of chronic stress in giraffes despite some inconsistencies among the individual biomarkers in the panel. In upcoming work, the team might revise the selection of biomarkers for the ALI panel to make it more effective. Possible additional biomarkers include haptoglobin, a protein associated with inflammatory responses, and interleukin proteins 2 or 6, which are present during immune responses.

Beer envisions that the ALI panel could be useful not only in zoos but also for farm, laboratory, shelter, or companion animals. “I’m excited about the broad application of this work,” she says. “I often wonder how it could revolutionize animal welfare and conservation efforts, and honestly extend into any environment where you might have captive animals.”

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.