Bird Flu Evolves on the Wings of Wild Birds

By Jameson Blount

Viruses that travel with migrating waterfowl can easily make the jump to humans.

May 30, 2024

From The Staff Medicine Immunology

Bird flu viruses are spreading around the world and could make the leap to humans at any time, experts are warning.

"Adaptation to our system is actually not that difficult for them, and our cellular machinery enables them to proliferate quite well," warns Vijay Dhanasekaran, a microbial ecologist at the University of Hong Kong School of Public Health. "We know that if a new virus emerges in humans, it's going to be catastrophic."

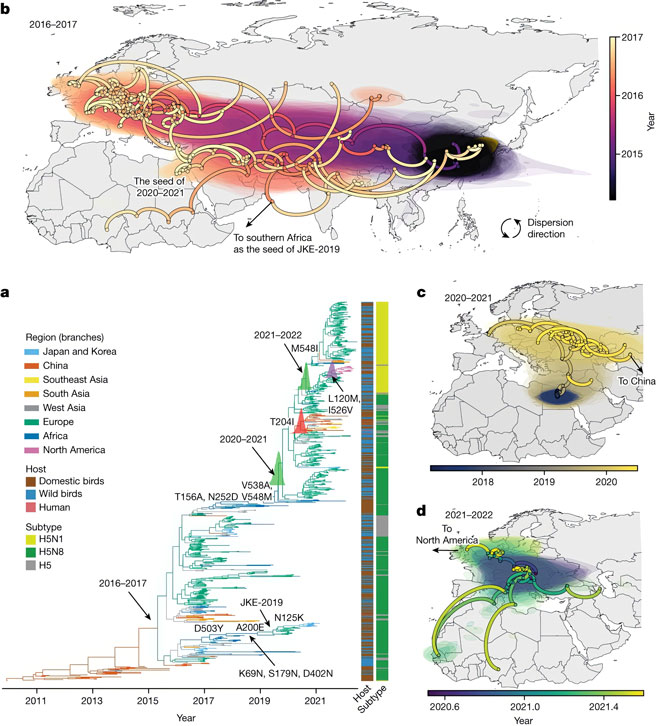

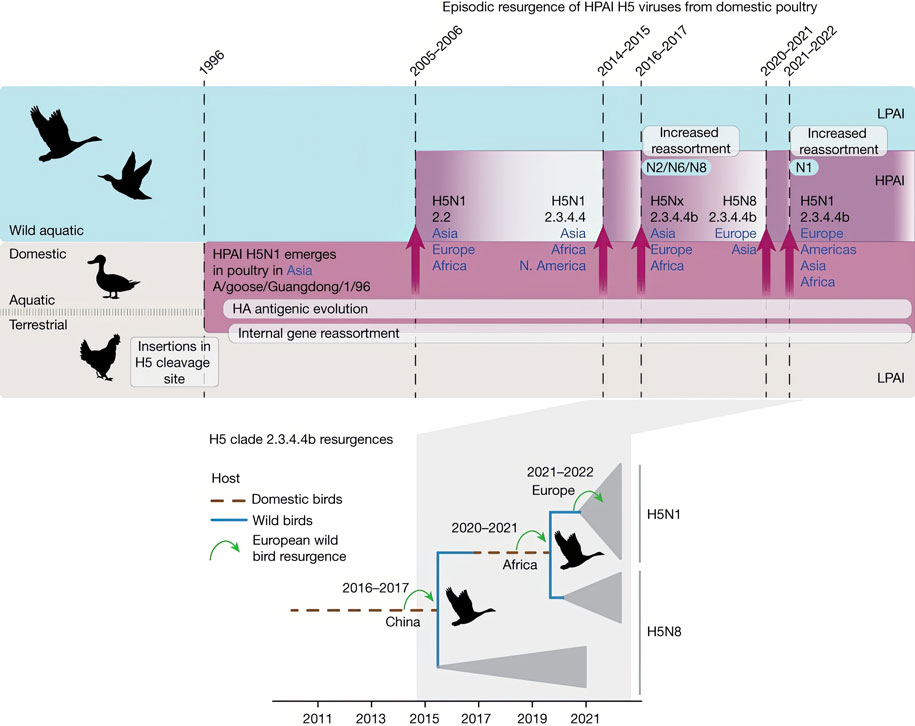

Until 2014, epidemiologists had only observed outbreaks of what are called highly pathogenic avian influenzas (HPAIs), which can cause severe disease, and even death, in domestic Asian poultry. However, Dhanasekaran and his colleagues have uncovered evidence that since 2014, these viruses have expanded their reach into North Africa and Europe by infecting both migratory wild birds and domestic poultry.

Image courtesy of Vijay Dhanasekaran

The researchers knew that HPAIs become more dangerous in domestic poultry by changing their own DNA in ways that allow them to infect more fowl. But outbreaks in domestic birds caused by these genetic changes were typically contained through culling or die-offs, and thus had limited potential to jump to mammals.

But Dhanasekaran and his team looked into the less-studied genomic changes that these viruses have recently undergone after infecting wild Asian ducks. They analyzed publicly available outbreak data reported to the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations and World Organization for Animal Health since 2005. Combining these sources with more than 10,000 whole genomes from other viruses enabled the researchers to simultaneously identify epidemic trends in bird flu ecology and evolution.

As Dhanasekaran and his team reported in the October 2023 issue of Nature, they analyzed the evolutionary development of the viruses to track how they were shifting and changing between outbreaks. They also developed statistical frameworks and simulations so that they could take information from outbreak reports and infer the genetic relatedness of the viruses based on their sequences, locations, and collection times.

Their findings indicate that within the past couple of years, most of the highly pathogenic strains causing the outbreaks came from an increasingly dominant group of viruses, and that this group has already moved into Europe on the wings of wild birds.

“The wild aquatic birds in particular are the natural reservoirs of influenza viruses, and a huge diversity of viruses can be found in these wild birds,” Dhanasekaran said.

Viral diversity is further driven by the fact that multiple viruses can infect a bird at the same time without killing it.

Image courtesy of Vijay Dhanasekaran

When two viruses infect the same cell, they can swap gene segments with each other, a process called reassortment. The influenza viruses in aquatic birds attach to receptors found in the guts of these animals, which happen to share a lot of structural similarities with the receptors found in the human respiratory tract.

Dhanasekaran says that a bird influenza virus only needs one big adjustment to jump into humans: “They don’t have to really adapt; all they really need is the receptor reassortment with the human seasonal virus and it’s got the whole package ready.” Although wild aquatic birds are crucial for viral diversification, transmission within domestic poultry is more often what leads to spillover into mammalian populations.

Before 2015, most of these viruses emerged from poultry in China, where they have been circulating for many years. Now that they are emerging in Africa and Europe—regions that have not previously experienced such infections—there is not only greater potential risk of pandemics, but also the environmental loss of native birds killed in the resulting outbreaks.

To compound the burden of these epidemics, the nations in these regions would likely need international help to prevent further resurgence events and spread. Dhanasekaran believes that the best response involves changing vaccination and control mechanisms within the poultry system. In the interest of human health, Dhanasekaran emphasizes the need for a more robust global effort to monitor and prevent outbreaks before they occur.

“The focus has been towards reducing poultry mortality,” he says, “rather than eliminating the virus from the poultry system itself.”

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.