Beyond Genetics

By Robert Frederick

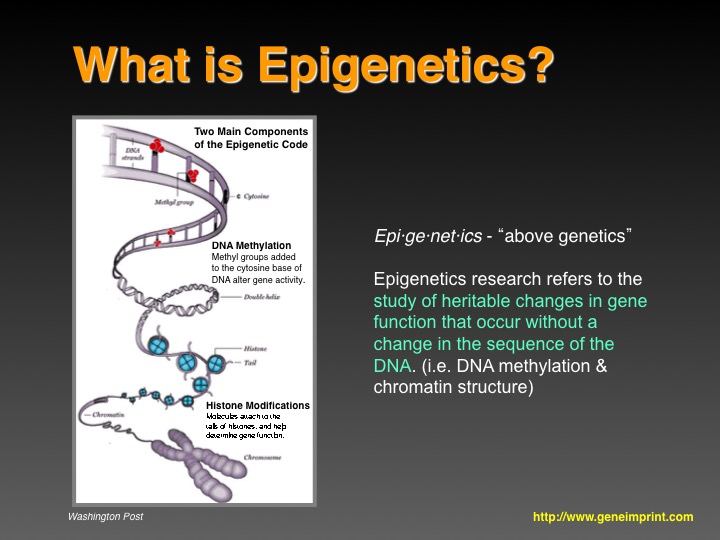

Why scientists are looking to our epigenome to better understand human health and disease.

March 7, 2019

From The Staff Biology Medicine Genetics Physiology

It didn't take long for the meaning of the two different discoveries to sink in. Shortly after Denise Barlow identified the first imprinted gene—meaning only the mother's or the father's copy of a gene works in the offspring—Randy L. Jirtle and his colleagues found that same gene was a tumor suppressor. "I was astonished and astounded," Jirtle said, "How could Mother Nature—and why would Mother Nature—turn off one copy [either the mother's or the father's] in something that was that important in tumor formation?"

With that question, Jirtle turned the whole focus of his lab to the then-nascent field of epigenetics. "This is huge and hugely important," Jirtle said in recalling that mid-1990s decision before the Research Triangle Park chapter of Sigma Xi (American Scientist is published by Sigma Xi). His talk last week, which was open to the public, is presented below in its entirety.

Image courtesy of Randy L. Jirtle.

"Epigenetics has always been all the weird and wonderful things that can't be explained by genetics."—Denise Barlow (1950–2017)

It was thousands of years ago that the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates purportedly directed people to "Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food." Whether a misquotation—or whether the notion does a disservice to food and to medicine—Jirtle's (and others') research provides plenty of evidence that food can serve as medicine via the epigenome. One of Jirtle's most famous examples is "The Agouti sisters" (pictured just below).

Image courtesy of Randy L. Jirtle.

Jirtle's lab also found that harmful exposures, such as to Bisphenol A (BPA), could be counteracted with dietary supplementation. Curiously, though, counteracting radiation exposure with antioxidants—known to reduce radiation lethality—revealed what's known as hormesis: that a small dose of radiation was actually beneficial to these mice.

After his talk had concluded and I turned off the video camera, I asked Jirtle whether radiation was unique among exposures because all life evolved with exposure to small amounts of radiation. The answer he gave was, I'll say, classic scientist: With an excited twinkle in his eye he replied "I don't know, but I'd sure like to find out."

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.