8 Myths About Public Understanding of Science

By Katie L. Burke

A little over a week ago, the Pew Research Center came out with new poll data showing that the general public continues to debate particular scientific ideas on which most scientists already agree. This has sounded the latest call for increased attention to public understanding of science. But this is a two-way street: There also needs to be a call for scientists’ understanding of the public.

February 9, 2015

From The Staff Communications

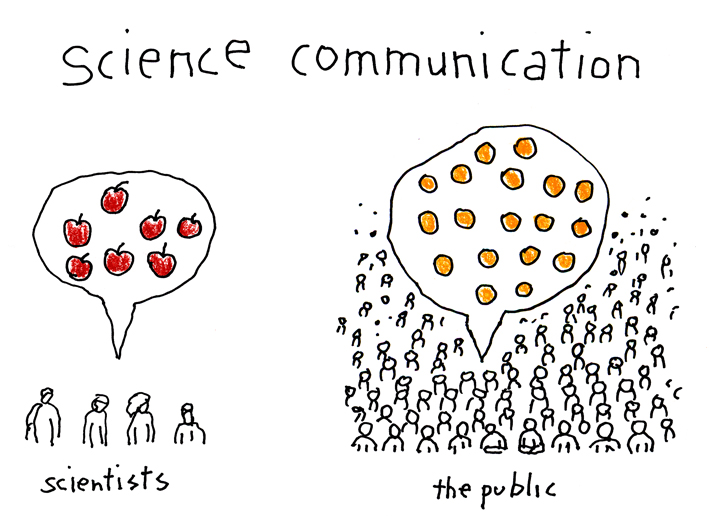

Cartoon by Tom Dunne

A little over a week ago, the Pew Research Center came out with new poll data showing what pretty much everyone already knows: The general public continues to debate particular scientific ideas on which most scientists already agree, including the reality of human-caused climate change, the necessity of requiring an MMR vaccination, and the validity of evolutionary theory. Pew’s data have sounded the latest call for increased attention to public understanding of science.

But this is a two-way street: There also needs to be a call for scientists’ understanding of the public. Many scientists harbor misperceptions about the public, ones that help exacerbate miscommunications. Common myths include:

- People need more information to understand science of concern to the public.

In truth, it’s not more information that people need—it’s better communication of that information. In the Information Age, people are flooded with—you guessed it—information. Giving people more information to consume is not going to cut through the noise, unless you can get people to pay attention and then listen. There are many ways to change communication: Language, length, presentation, framing, venue, medium, and sources used are all important. For starters, communication can be improved by understanding the language and sources of information valued by an audience, as well as their misperceptions and fears about a particular issue. - It is the public’s responsibility to learn scientific information of policy concern.

Actually, it is not just the public’s responsibility to learn this information—it is also the experts’ responsibility to communicate it well. - Science literacy in the United States is declining.

Not exactly. Science literacy among adults in the United States is increasing. Nevertheless, science literacy is still much lower than is appropriate for an informed citizenry (it’s just always been low). (Don’t worry, I’m not saying we don’t need better science literacy. In fact, the recent Pew Research poll shows that most Americans feel that current K–12 STEM education leaves much to be desired. Indeed, according to Jon D. Miller in his chapter in the 2011 book The Culture of Science: How the Public Relates to Science Across the Globe, the increase in science literacy among adults is largely due to college-level education and informal learning resources, but science literacy among secondary school graduates has not increased.) - People who question the science on these issues lack education.

Nope. Parents who refuse to vaccinate their children mostly hold college degrees. Those who are most polarized in their support for or denial of climate change are the most highly educated of both of those groups. - Arguments supported by facts and evidence will change people’s beliefs.

Factual and evidence-based arguments do not change most people’s beliefs. Scientists are also much more comfortable questioning each other’s evidence behind their arguments, but most people do not find this convincing and some may actually see this as an indication that the scientist is part of the problem. - Disagreements are about the facts, which people just do not understand.

At their core, these policy-relevant disagreements are not really about facts; they are about people’s values. People disbelieve scientifically supported information when they feel they must do so to protect a deeply held value. In fact, people become frustrated with experts when they seem insensitive to these values. - Scientists know how to talk in a way that the public will understand.

Unfortunately, this usually isn’t the case. Although scientific training includes specific language and communication devices designed to enable researchers to communicate clearly with colleagues, this common parlance among scientists does not necessarily communicate ideas effectively outside that circle. Many scientists speaking to the public do not spend enough time studying the lexicon and concerns of their audience to meet them where they are. - Public trust in science has decreased.

Although trust in scientists among conservatives and churchgoers has declined, overall trust in science among the general public has stayed rather stable. When public trust in science has gone down, it’s been for brief periods when public trust in everyone has gone down, like after 9/11/2001 and the beginning of the Great Recession. Typically, people who are warm and competent are more likely to be seen as trustworthy. Scientists are not always seen as warm, although they are generally seen as competent.

In the grand scheme of things, most people consider what scientists have to say valid, which is better than most other professions have it. When scientists communicate well, their opinions are valued more. The links in this post are a good starting point for learning more about improving science communication.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.