In Deep: Deepwater Well Control

By Barbara Aulicino, Dianne Timblin

Oil drilling 1,500 meters under the sea is complicated, and the Deepwater Horizon still offers valuable lessons.

May 11, 2018

From The Staff Engineering Environment Geology Human Ecology

Editor's Note: On July 5, the comment period on the proposed changes to the well-control rules—that are discussed in this post—was extended from July 10 to August 6. As of the writing of this note, July 11, the Federal Register site still says July 10, but the public may comment here on the proposed rule change until August 6, 2018.

As you’re reading this, some extremely important people are out in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico. They’re working a 12-hour shift—monitoring sensor readings, performing calculations, making adjustments. They’re aboard offshore oil rigs, and it’s their responsibility to prevent cost overruns for their employer, or more likely the company that has contracted them. Critically, they must also protect everyone on the rig by preventing an influx of highly combustible hydrocarbon gas while also keeping the Gulf waters free of leaked oil. If they perform these duties successfully, they’ve pulled off a complicated, difficult maneuver with a deceptively simple name—well control.

The work taking place on these rigs is part of the massive industry and infrastructure supporting the discovery, procurement, refinement, transport, and distribution of hydrocarbon products. More than 10 million people work in the U.S. oil and gas industry, and the sector comprises almost 8 percent of the nation’s economy. Most of the time, the work proceeds within its routines smoothly, and consumers rarely think about it. Nonetheless, just because a process is routine doesn’t mean it’s easy—or prevent it from being dangerous.

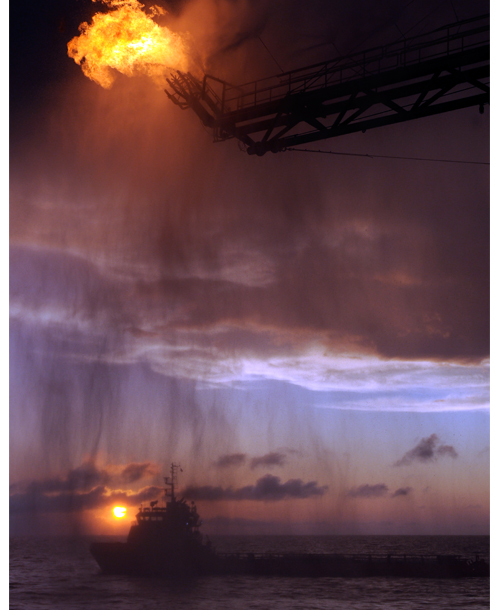

The dangers of the work became all too plain on April 20, 2010, when the Deepwater Horizon, a semisubmersible rig that had been drilling a well in the Gulf’s Macondo prospect, suffered a blowout. Hydrocarbon gas entered the well and sped upward to the rig, where it ignited, causing explosions that killed 11 workers and injured 17. The rig was immediately evacuated and continued to burn for two days before capsizing and sinking. Oil from the Macondo well spewed into the Gulf for three months before the well was at last successfully sealed.

U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Patrick Kelley.

Following the disaster, media reporting, legal procedures, scholarly studies, and government investigations proceeded to examine a complex array of problems that had converged at the Macondo well, intending to tease out the strands that might best explain what went wrong. The objective in some cases was to convey facts to the public; in others, to assign blame. Some studies, however, have extended beyond those objectives to examine the complex array of factors involved—such as the equipment used, the planning processes, the actual execution to plan, and the organizational responsibilities and relationships—and how they interrelate. Ultimately, this approach aims to contribute to a body of knowledge that may prevent similar catastrophes.

Even as disagreement continues (and may always remain) about which of many contributing factors was most to blame, this interrelational approach is proving to be of lasting use to those interested in learning from the tragedy. Deepwater Horizon: A Systems Analysis of the Macondo Disaster, by engineers Earl Boebert and James M. Blossom, is essential reading in this genre. As Brian Hayes explains in his review, Boebert and Blossom’s “telling of the story features neither heroes nor villains. Their focus is first on the technical challenges that need to be overcome to safely drill an offshore well, and second on organizational factors—the planning process, decision making, patterns of communication, and adherence to established procedures.”

On April 28, 2016, after six years of investigation into the Deepwater Horizon disaster and extensive discussion with stakeholders in the offshore drilling industry, the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement released new regulations. The name—“Oil and Gas and Sulfur Operations in the Outer Continental Shelf—Blowout Preventer Systems and Well Control,” informally dubbed the Well Control Rule—refers explicitly to well control, and the regulations stemmed directly from lessons learned about the causes of the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

But the story doesn’t end there. The environmental fallout of Deepwater Horizon continues, as does the research to better understand it.

And today, following new rounds of rule assessments, the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement proposed revisions that curtail some of the well control regulations enacted back in 2016. The bureau has embarked on 60-day period of public commentary: It invites responses to the proposed rule changes until July 10.

Under some circumstances, curbing regulations that have proven unnecessary can serve a useful purpose. Duplicative reporting, for instance, consumes valuable time, and in a hazardous workplace it could distract from the safety focus itself.

But it’s important to weigh such regulation changes carefully to determine whether the rules targeted for deletion truly are unnecessary for all stakeholders. And in the case of well-control regulations that have been in effect for two years, it’s also important to consider whether they’ve been in place long enough for such a determination to be made.

To weigh these regulations and the proposed changes—or simply to understand a critical aspect of obtaining the fossil fuels most of us depend on—some familiarity with the basics of well control is essential, especially as practiced in the context of offshore drilling. The concepts are not common knowledge outside the industry, so we’ve put together a well-control backgrounder, included below, that we hope will help.

In the petroleum business, getting the details right—and creating a work environment that encourages attention to these details time and time again—can be lifesaving. Given that oil operations in the Gulf are expected to increase (as are offshore drilling operations elsewhere in U.S. coastal waters), practicing sound offshore well control will only become more important. Whatever lies ahead, the folks out in the middle of the Gulf, or wherever their rig may be, should have the best chances of remaining safe, day in and day out.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.