Eliminating Sex Bias in Biomedical and Clinical Research

By Robert Frederick

A surgeon discovers her own research is sex-biased and becomes an effective advocate.

November 13, 2018

From The Staff Biology Medicine

After Melina Kibbe discovered that the cardiovascular therapy she was researching was promising, she told a colleague about it.

"That's interesting," her colleague responded, "What are the similarities or differences between males and females?"

Kibbe had no answer. As was common practice in her field, she had conducted her research only on male rats.

Subsequently receiving a grant from that same colleague to repeat her study on female rats, Kibbe discovered that her cardiovascular therapy was promising only in male rats; it had the opposite effect in female rats.

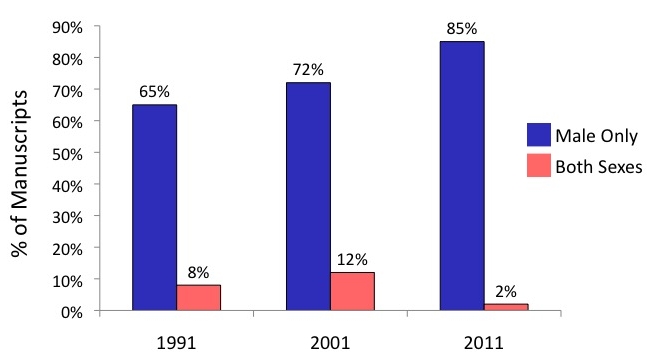

As Kibbe herself has since researched, the biomedical and clinical research pipeline is highly sex-biased (referring to XX and XY, chromosomal-based sex). In surgical research it appears to have become even more so over the past few decades.

Image courtesy Melina Kibbe from Yoon et al., 2014, Sex bias exists in basic science and translational surgical research, Surgery 156(3):508-516.

There's a well-known history of how women of child-bearing age came to be excluded from early clinical trials given birth defects and other negative health outcomes resulting from fetal exposure to certain drugs. But in 1993, those rules excluding women were reversed, and as recently as 2016, a rule now seeks the "participation of diverse groups of women in clinical research." (A recently prepared timeline titled "Understanding Sex Differences at FDA" provides links to the agency's sex and gender consideration over the years, starting in 1977.)

But as to why those practices of excluding women of child-bearing age were extended to female cells and animal studies seems to be mostly about eliminating variables in cell-based studies and reducing the financial cost of animals because "transgenic animals in particular are rare, are difficult to breed, and can cost thousands of dollars apiece," writes neuroscientist R. Douglas Fields. Fields was arguing against a 2014 rule that requires scientists funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to "report their plans for the balance of male and female cells and animals in preclinical studies in all future applications, unless sex-specific inclusion is unwarranted, based on rigorously defined exceptions."

Not so coincidentally, that 2014 NIH rule came about just a few months after Kibbe—who had contacted many media outlets in order to tell her story of her own sex-biased research—appeared on 60 Minutes. She's been telling her story over and over ever since.

I heard Kibbe's story—complete with visuals, an excerpt of the 60 Minutes report, and even how she learned that The Colbert Report had covered it (see video, below)—at a recent talk sponsored in part by the Research Triangle Park chapter of Sigma Xi (publisher of American Scientist).

Video by Robert Frederick.

In telling her story, Kibbe has gone well beyond publishing the negative results of her own research on female rats, a practice some argue is a "moral imperative." She's become an advocate for eliminating sex bias in biomedical and clinical research, starting with the television report and continuing through a new rule at the NIH. So far, she says the outcome of her advocacy has been a "beautiful thing," and that she plans to keep telling her story until sex-biased research is eliminated.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.