The Twilight Zone Turns 60

By John Kessel

The strange mix of horror, science-fiction, drama, and comedy exposed the hidden aspects of human nature, then and now.

October 3, 2019

Science Culture Art Communications Psychology Sociology

Back in 1959, when I was nine years old, control of what we watched on our 19-inch black-and-white Admiral TV rested in the hands of my parents. For the most part this was not a problem; I was content watching Gunsmoke or Wagon Train or Bonanza, but Friday nights brought frustration. There was this new series, a science fiction show, that my parents would not let me watch because it was too scary for a kid.

The Twilight Zone premiered on CBS on October 2, 1959. Competing for attention with 77 Sunset Strip and Rawhide, in the middle class white America of the 1950s, an era when three out of four dramatic series were westerns, a science fiction anthology show with no continuing characters was seriously weird. What did space aliens and time travel have to do with the real world? How could children grow up to be realistic adults if their heads were filled with such nonsense?

But somehow The Twilight Zone lasted five seasons, 156 episodes, until 1964. And I managed to watch it despite my parents' concern for my mental health.

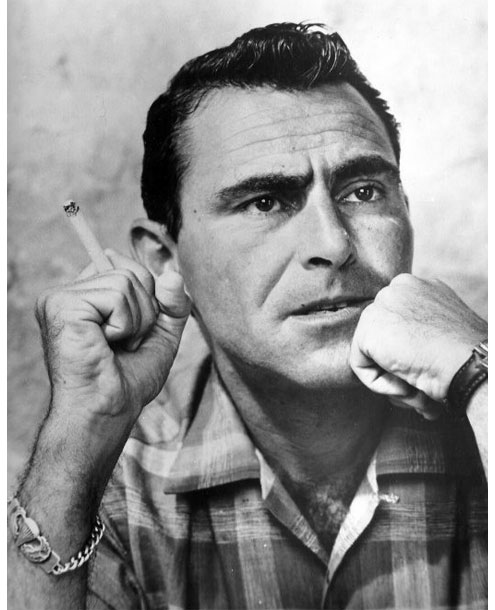

Wikimedia Commons.

The show created a mystique from its very beginning. Its opening, Rod Serling's voice and Marius Constant's electric guitar/bongos/horns over a series of surreal images, was unlike anything else on TV. The stories mixed the strange with the mundane. They portrayed an ironic universe where supernatural events or scientific progress exposed the characters of the people who encountered them. All this presided over by the chain-smoking Serling, his dry commentary creating a sardonic mirror of mid-20th century America.

The majority of the scripts were written by Serling, Richard Matheson, and George Clayton Johnson, but the series also adapted stories by established writers of the fantastic like John Collier, Damon Knight, Jerome Bixby, and Ray Bradbury. A cavalcade of character actors familiar from old movies, and of others later to become famous, populated the episodes: Burgess Meredith, Ida Lupino, Robert Redford, Ron Howard, William Shatner, Lee Marvin, Dennis Hopper, Leonard Nimoy, Robert Duval, Burt Reynolds, and Peter Falk, to name a few.

In an interview at the time, Mike Wallace suggested to Serling that by working on this series he had "given up on writing anything important for television." But the secret of The Twilight Zone was that it used science fiction and fantasy not to escape from the world, but to critique it.

Serling, one of the great scriptwriters of the first decade of U.S. television, author of such notable works as Requiem for a Heavyweight, had grown frustrated by networks interfering with his scripts. He thought that, if he could couch his commentary as fantasy, he could fly under the radar of the censors. Twilight Zone episodes questioned political and social realities of the 1950s: the Cold War, the arms race and the threat of nuclear annihilation, racial discrimination, McCarthyism, consumerism, and the shallow culture of beauty.

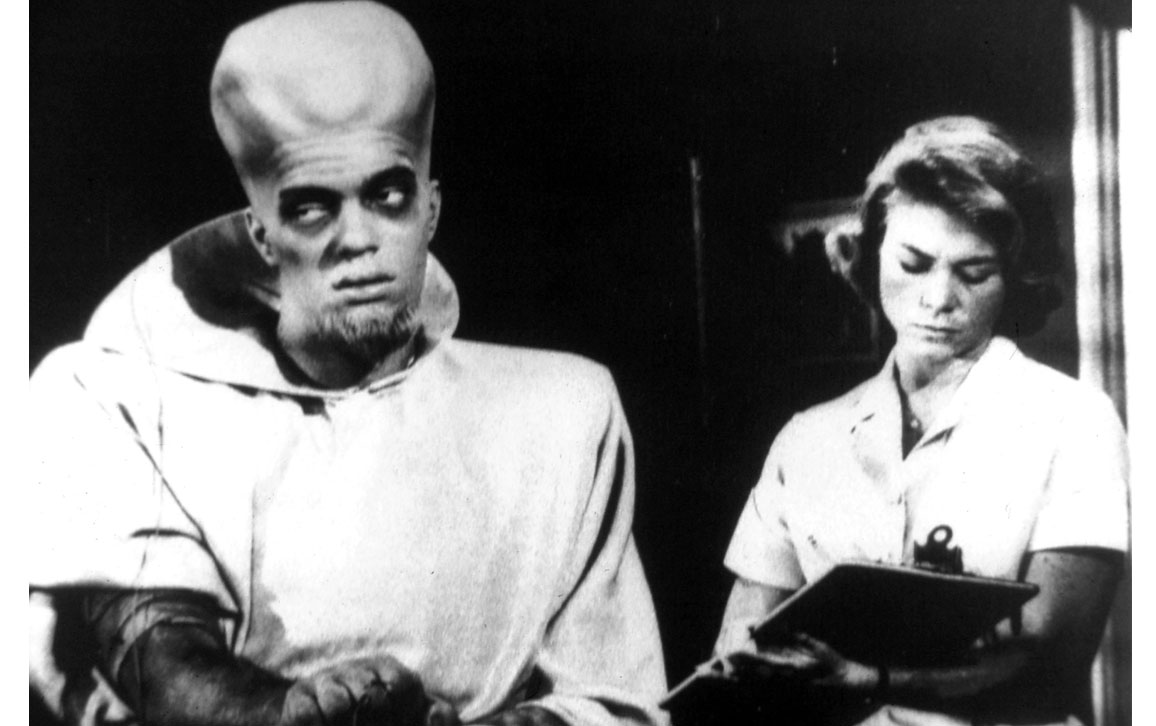

Alamy

At its weakest (and some of the episodes were weak indeed, one-joke stories with "surprise" endings predictable after the first 10 minutes) The Twilight Zone purveyed sentimental pleading, shopworn moralism, and sophomoric attempts at profundity.

At its strongest, The Twilight Zone pried the lid off American life to show the gears working beneath. These episodes still have the power to unsettle today.

Contemporary politicians and opinion makers seek to "create narratives" in order to persuade people. Stories are powerful. As John Gardner said, "Nothing in the world has greater power to enslave than does fiction."

Serling believed in the power of storytelling to shape the minds of viewers, and saw in television a great opportunity, not to enslave, but to liberate.

To me personally, this is the most lasting legacy of The Twilight Zone.

Alamy

My generation of science fiction writers—those born in the late 1940s to early 1950s, who were teenagers when the original series aired—were imprinted, for better or worse, with this aesthetic. Stories by James Patrick Kelly, Connie Willis, Nancy Kress, Karen Joy Fowler, and many others show evidence of this influence. For example, Kress's 1985 story "Out of All Them Bright Stars" tells of a waitress in a roadside diner on an evening when a blue alien comes in to be served. The story is, among other things, an allegory of race, telling us more about human beings and their differing reactions to the other than it does anything about aliens or outer space.

Kelly's story "Dancing with the Chairs" takes place in a bar where a divorced man gradually becomes invisible; Willis's "A Letter from the Clearys" presents an American family struggling to survive a nuclear war, sabotaged by their daughter whose psychological terrorism suggests the causes of that war. My own "A Clean Escape" considers whether a politician who cannot remember the crimes he has committed is still guilty of them. All of these might have been episodes of The Twilight Zone; some of them have been dramatized on shows like Masters of Science Fiction that are its clear descendants.

Over the last 60 years there have been many such descendants, from The Outer Limits to Black Mirror, to say nothing of the several later iterations of Serling's original (including CBS's recent reboot). Though none of these has perhaps quite captured the lightning that Serling bottled in 1959, they demonstrate the continued attraction of the concept.

The Twilight Zone was not scary in the same sense that creature features of the 1950s were. It was the subversiveness of the ideas that was scary: that the comfortable gloss our parents put on reality was flawed or incomplete. That all the givens of our suburban life could be—ought to be—interrogated.

In 1959 neither my parents nor I could know that I would grow up to write science fiction, but the science fiction I was later to write consciously or unconsciously, owes a great deal to the seeds planted by Rod Serling 60 years ago.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.