How Living in a Racist Society Makes People Sick

By Flora Taylor

Anti-Black racism in the United States influences health outcomes in myriad ways. In her gripping book Sickening, Anne Pollock illuminates them using a wide range of case studies.

June 22, 2022

Science Culture Ethics Medicine Review Scientists Nightstand

SICKENING: Anti-Black Racism and Health Disparities in the United States. Anne Pollock. 202 pp. University of Minnesota Press, 2021. Paper, $21.95.

For an illustration of Pollock's method for analyzing social injustice, see this essay by Jasmine Johnson.

As a professor of science and technology studies, Anne Pollock has spent more than a decade teaching undergraduates about the ways in which science, technology, and medicine shape and are shaped by society and culture. She wrote Sickening: Anti-Black Racism and Health Disparities in the United States, she says, to give readers of all backgrounds a foundation for understanding key topics in racism and health, and to augment the macroscopic, quantitative work of epidemiologists by showing the health effects of racism in individual lives.

In each of the book’s six core chapters, Pollock uses journalistic and academic accounts of a multifaceted event to tell a story, adding context as she explores what the event reveals about “medicine as usual.” These six case studies demonstrate that racial inequality in health is not just a legacy of past oppression but is constantly being re-created in the present. The cases, which deal respectively with terrorism, natural disaster, mass incarceration, environmental justice, police brutality, and reproductive justice, reveal that racial health disparities are the result of “wide-ranging and interconnected elements of living in a racist society.”

Pollock is an excellent storyteller, and her accounts of the cases she has selected are vivid.

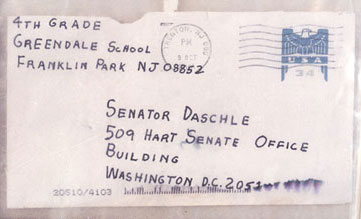

Chapter 1, for example, opens with a transcript of the initial portion of a 911 phone call made on October 21, 2001, by Thomas L. Morris, Jr., a Black postal worker who believes he may have been exposed to anthrax through his job. Pollock soon interrupts the transcript to let us know that after Morris was taken to the hospital by ambulance, he died later that same day of inhalation anthrax (as did his Black coworker Joseph Curseen). She fills us in on the context: A letter containing anthrax spores had been mailed to Senator Tom Daschle in the aftermath of 9/ll; the Capitol building, where the letter was received, was evacuated and thoroughly cleaned, and all its workers (and even dogs who had been in the building) were tested and given prophylactic antibiotic treatment. However, at the postal facility that had processed the letter, where Morris and Curseen worked, no testing or treatment was implemented, and the employees (92 percent of whom were Black) were told they were not at risk and should continue working as usual; the possibility that they might need medical care was not prioritized.

Having made us aware of the glaring disparity between these two responses to potential anthrax exposure, Pollock takes us back to the transcript of the 911 call, where Morris reports that he is experiencing difficulty breathing and his chest feels constricted. He patiently explains to the 911 operator that although he was told by his employer that the envelope processed at their facility did not contain anthrax, he doesn’t believe that to be true. He says that despite having been told at work that he wasn’t at risk, when he started to feel sick he went to the doctor and explained that he might have been exposed to anthrax; but the doctor told him that it was probably just a virus, that he should just go home and take Tylenol. The doctor did take a swab to test for anthrax, but then he never got back to Morris with any results.

Pollock contrasts Morris’s fate with that of another of his Black coworkers, Leroy Richmond, who developed a fever and was told by a nurse at work that it was nothing to worry about, and was told by a doctor at his health maintenance organization (HMO) that he didn’t seem very sick. But unlike Morris, Richmond refused to accept what he was told and go home; instead, he went to the emergency department and refused to leave. He finally was admitted to the hospital, where he received treatment for a month and therefore survived.

Often we’re told that health disparities are the result of Black people distrusting the medical establishment because of past abuses, such as those that occurred in the 1932-1972 "Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male." But Morris and Curseen did trust the medical establishment, and it let them down; it was Richmond’s mistrust and skepticism that saved him. Literature on racial disparities in health care often focuses on poverty, lack of education, lack of insurance, and failure to seek care. But Morris and Curseen were not poor; they were employed, insured, and reasonably well-educated (Curseen had a college degree, and Morris knew the signs of anthrax infection). The two men did seek care, but racial profiling presumably contributed to their failure to receive it. A 2013 study by Leslie Hausmann and others found that physicians often stereotype African Americans as drug-seeking and deny them pain medication; they may also deny them optimal treatment because they stereotype them as noncompliant. The likelihood that care will be inadequate is even greater if a physician is under pressure from an HMO to limit the time spent with patients and to minimize medical treatment. (Morris and his coworkers all belonged to the same Kaiser Permanente HMO.)

Throughout the chapter, Pollock gives both urgency and poignancy to her narrative by returning repeatedly to the transcript of Morris’s 911 call as he explains his history to the operator while struggling to breathe. She describes the responses to the postal worker deaths by officials (who claimed that no one should be blamed but the terrorists) and the media (coverage in the United States, in contrast to that in Great Britain and Canada, seldom even mentioned that the postal workers who died were Black).

In chapter 2, the public event is Hurricane Katrina, and Pollock focuses on the fact that the storm resulted in increased morbidity and mortality from chronic disease among Black people as a result of both psychosocial stress and disruptions in access to prescription drugs. (For instance, at the Superdome, by some accounts the National Guard was instructed to confiscate all drugs from the people entering; this included any pharmaceutical drugs not in their original packaging. “Those seeking shelter were treated as presumptive enemies in the drug war,” observes Pollock.) Chapter 3 explores the ways in which racist mass incarceration affects access to health care by examining the case of two sisters in Mississippi, Gladys and Jamie Scott, who had been sentenced to life in prison in 1993 but in 2010 were offered suspended sentences on the condition that Gladys donate a kidney to Jamie, who had kidney failure (the state wanted to be rid of the ongoing expense of paying for Jamie’s care). Chapter 4 identifies environmental racism in the actions of officials in Flint, Michigan, who during the water crisis there gave first priority for safe water to the machines at General Motors. Chapter 5 explores the role of segregation in an incident of police brutality toward a Black teenager at a swimming pool party in suburban Texas in June of 2015. And chapter 6 addresses reproductive injustice in an exploration of Serena Williams’s brush with maternal mortality when her caregivers were slow to fulfill her request that she be tested for pulmonary embolism after her daughter’s birth by cesarean section in 2017.

From Sickening

Pollock gives analytic meaning to the individual experiences she describes by tying them to the social structures in which they emerge and showing how they illustrate structural inequality. In the book’s concluding chapter, she finds echoes of themes from the case studies in the coronavirus pandemic and in the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd. As Jasmine Johnson discusses in her essay on Sickening, Pollock also provides a template for analyzing social injustices—a template that the book’s case studies show in action. And she encourages readers to find a way to get involved in taking action to address the injustices she has described, noting that medical professionals can join organizations such as White Coats for Black Lives.

Sickening does a very good job of demonstrating that “health is more than a medical matter.” To promote the well-being of Black people in the United States, changes are needed not just in health care but in the legal system, housing policies, policing, and prisons.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.