This Article From Issue

November-December 2006

Volume 94, Number 6

Page 563

DOI: 10.1511/2006.62.563

Lost Mountain: A Year in the Vanishing Wilderness. Erik Reece. xviii + 250 pp. Penguin Press, 2006. $24.95.

By him first

Men also, and by his suggestion taught,

Ransacked the center, and with impious hands

Rifled the bowels of their mother Earth

For treasures better hid.

—Milton, Paradise Lost

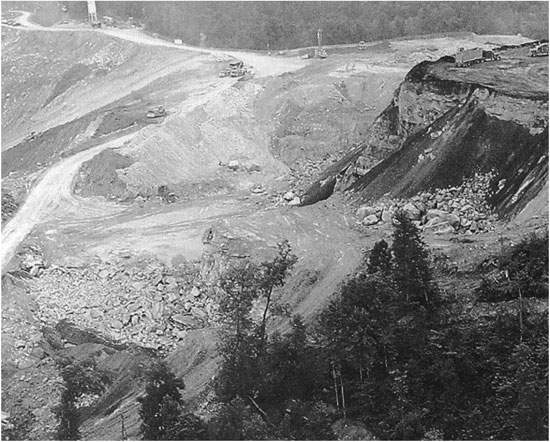

Lost Mountain still exists on my Rand-McNally map of Kentucky, but it is now gone forever, a casualty of our national obsession with cheap electricity. It is one of 456 mountains in the Appalachians leveled to get at the upper seams of coal that underlie one of the oldest and most diverse and beautiful ecosystems on Earth. The form of mining is called "mountaintop removal," which means blasting away the peaks and dumping all that is not coal into thevalleys. The devastation is mostly hidden from public view and is never included in the glib talk about "clean coal." So far, 1.5 million acres have been decimated, and the practice is metastasizing across four states with nary a whisper of protest from law-makers in Washington.

From Lost Mountain.

Erik Reece's Lost Mountain, a well-crafted report on blood and ruin in the coal fields of Appalachia, harks back to earlier accounts such as Harry Caudill's 1963 book Night Comes to the Cumberlands. The difference is that of scale. As bad as coal mining has always been, it is even worse now because of the size of the equipment used and the ongoing failure of elected officials to protect the land and people of the Appalachians. President Bush and Kentucky senator Mitch McConnell, among others, have been the recipients of hundreds of thousands of dollars of campaign contributions from the coal industry. And the head of the Mine Safety and Health Administration reports to McConnell's wife, Labor Secretary Elaine Chao. The conflicts of interest are apparent, but the power of the coal industry has long manifested itself in this region, which has been sacrificed to ensure a supply of cheap energy for other parts of the country.

Reece is a gifted writer, and the detail and specificity he provides make the story both poignant and valuable. The Appalachians, he explains, have been the seedbed for the continent after successive ice ages. They are among the oldest mountains in the world and represent one of the most diverse ecologies found anywhere on Earth. But this is not just a tale of environmental ruination. The blasting, coal washing and valley filling create deep human suffering, raising issues of decency, fairness and justice. Coal companies routinely dump toxic chemicals that later show up in what passes for drinking water. Reece remarks of one such instance that

the most sinister part of this whole sad story is that it was all done intentionally. A multinational corporation hid in a hollow of one of the poorest counties of one of the poorest states, and knowingly dumped hundreds of deadly chemicals right on the ground.

Poisoned water is only one of a number of potentially deadly side effects of coal mining. Coal dust can cause black lung and silicosis; overloaded coal trucks careen down perilous mountain roads; boulders dislodged by blasting endanger nearby houses; deforestation leads to flooding; and influxes of toxic slurry threaten to burst dams on hundreds of ponds. Hopelessness, too, probably takes its toll, but never appears on a death certificate. "There's blood," Reece writes, "everywhere you look."

Are these horrors necessary? The author says no. Were we forced to pay the true costs of electricity, we might "begin to think about smaller homes, better insulation, fluorescent lighting, strategically placed shade trees, and solar hot-water heaters. The technology is there; we simply lack the will." Coal from the removal of mountains in Appalachia supplies about 4 percent of our total national use, and coal burning represents half or more of our national emissions of CO2, contributing to climate destabilization.

Aside from state and federal action to promote efficiency and renewable sources of energy, what can be done? Reece believes that it is possible to create "an industry around real reclamation in the mountains." The Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative has, according to Reece, "developed a successfully tested plan to bring forests back to strip mines." The key, apparently, is to replant without first compacting the soils and mining debris. In Kentucky, 1,500 acres have been "truly reclaimed" using methods pioneered by the ARRI. Although this may be a promising way to mitigate some of the problems caused by mountaintop removal, one hopes that it will not be used to justify practices that ought to be terminated altogether.

Looking down on the shattered remnants of Lost Mountain, Reece reflects that "I am surrounded by the work of conquerors, not members of any land community. No one who felt a responsibility to other citizens within a community would destroy its water, homes, wildlife, and woodlands." And, one might add, no decent society would deprive its citizens and its children of life, liberty and property so wantonly and coldly. Reece concludes by saying,

Material gain, speed, and convenience are the most dominant forces within this country, and they have done much to crush the spiritual, ethical, and aesthetic elements of our nature. If we understood the natural world as a spiritual presence, we would also see that all living things are kin to us.

Lost Mountain is a story well told, both eloquent and moving. It is a requiem for "a landscape worthy of comparison to an earthly paradise." But it is also a story written in the hope that we might one day regain control of what Henry Adams once described as "the law of acceleration," by which he meant the exponential and unbridled advance of human civilization. Doing so will require that we place the destruction of Appalachia on a wider topography of industrial ruin that includes climate destabilization, the possibility of more Katrina-scale storms, heat waves and droughts, and human suffering that we have neither words to describe nor, yet, the wit and policies to alleviate.

In the end, Lost Mountain is a story of political failure—of the corruption of democratic politics by coal companies, timber barons, and land owners who bled the region of its resources, youth and pride. But no good book is purely a lament, and this one certainly is not. Instead it looks forward to a better era when at last we will have built a culture to match the peaks of Appalachia. And we have neither time nor mountains to waste.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.