This Article From Issue

November-December 1998

Volume 86, Number 6

DOI: 10.1511/1998.43.0

Galileo's science sprang from the same roots as the Jesuits' program, and it shared much of its spirit with Jesuit mathematicians. The dynamics of Galileo's own development, however, pushed him into formulating a different agenda.

"The Use and Abuse of Mathematical Entities: Galileo and the Jesuits Revisited," Rivka Feldhay,

The Cambridge Companion to Galileo

Peter Machamer, ed.

Cambridge, $59.95

From My Brain is Open.

[Sir William] Crookes noticed that his [invention, the cathode-ray] tube fogged photographic film sealed inside a light-tight envelope. From that observation, Crookes concluded that "nobody should leave film near the cathode-ray tube." But when Wilhelm Roentgen ruined some film in the same way a few years later, the experience led him to invent the x-ray machine. The moral, according to Erdos? "It is not enough to be in the right place at the right time. You should also have an open mind at the right time."

My Brain Is Open: The Mathematical Journeys of Paul Erdos

Bruce Schechter

Simon & Schuster, $24.50

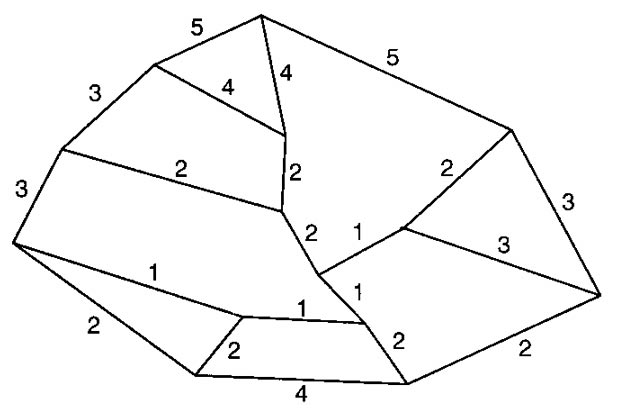

Quantum-spin networks defining Planck-scale spacetime geometry are a possible site for proto-conscious "funda-mental" experience. In this view, various configurations of quantum-spin geometries represent different varieties of raw experience. Below: A spin network, introduced by Roger Penrose as a quantum mechanical description of the geometry of space.

From The Geometric Universe.

"Funda-Mental Geometry," Stuart Hameroff,

The Geometric Universe: Science, Geometry, and the Work of Roger Penrose

S. A. Huggett, L. J. Mason, K. P. Tod, S. T. Tsou, N. M. J. Woodhouse, eds.

Oxford, $45

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.