This Article From Issue

March-April 2019

Volume 107, Number 2

Page 121

The natural, untouched world is not the domain of archaeology, which focuses instead on places modified by humans in the past. But what constitutes the past? In Adventures in Archaeology, P. J. Capelotti, a professor of anthropology at Penn State Abington, argues that even recent movie props and roadside attractions hold value in understanding human culture. “For archaeologists, was not everything in our field of study artificial? Artifact and artificial are practically the same word,” he writes. Capelotti explores preservation and discovery from the Arctic to outer space, but he encourages attention to history that is more immediately available but often overlooked. In this excerpt he recounts a project in “garbology” on a dump site in the mud banks below an 1850s riverfront mansion in Philadelphia, called Glen Foerd on the Delaware, to show that “modern human waste disposal could be as revealing of human behavior as a prehistoric midden thousands of years old.”

The mud bank is underwater for more than half the day. When the tide goes out much of the bank is uncovered, but even this uncovered segment is difficult to access because of loose mud and, in summer, a thick foliage of water plants making the mud surface inaccessible. These same environmental factors, however, seem also to have acted to preserve and protect the artifacts embedded within the mud bank. The area is not easily accessible from landward, and to land from the creek or river requires a shallow draft boat such as a kayak, canoe, inflatable, or jon boat.

When we climbed down to the mud bank in the spring of 1998, we found several examples of intact bottles with embossed brand names. This discovery led to additional visits over the next three summers, always at low tide, and with undergraduates from my introduction to archaeology courses at Penn State Abington. We laid out a baseline and placed five grid squares along it. This completed, we began to record and recover hundreds of artifacts of glass, porcelain, and metal.

From Adventures in Archaeology.

As we ended our third summer of occasional visits to the site in August 2001, we had collected hundreds of glass and porcelain fragments as well as a remarkable number of intact bottles. The presence of so many intact bottles strengthened our feeling that we were at a dump site, as it would be unlikely for so many bottles to have traveled downstream and survived the turbulent tumbling of the tides along the mud and sand of the creek without fracturing.

The Glen Foerd estate is preserved in part as an example of “turn-of-the-century wealth and industry,” or what the wealthy of a century ago believed was important. As we began a more intensive examination of the mud bank below Glen Foerd in the late 1990s it was with the goal of learning something of the objects tossed away by “turn-of-the-century wealth and industry” and its servants.

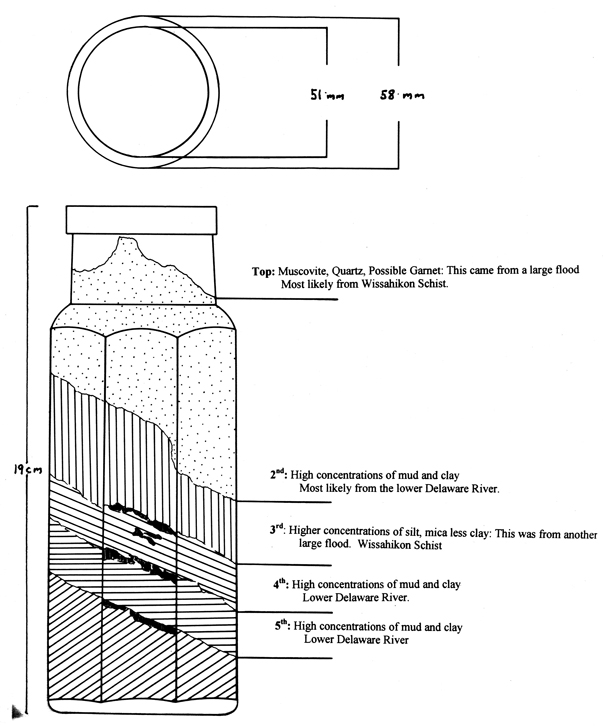

Among these intact bottles was an apparent Heinz pickle bottle that had remained in an upright position, so far as we could tell, for a century, recording in its narrow confines a remarkable stratigraphy of the passage of sediment-bearing floods.

We shifted the many bottles and plate and cup fragments to a makeshift archaeology lab at Penn State Abington. There it soon became clear that most of the samples date from approximately 1900 to 1939, with the majority dating to the 1920s and 1930s. With some notable exceptions, the bottles reflect summer party use, as they include numerous Heinz ketchup and pickle bottles.

The other significant number of intact bottles seems to indicate a concern with personal health and well-being on the part of people living on the estate. Among these are a Kruschen Salts bottle (a laxative used in the 1930s), an Omega Oil bottle (a kind of turn-of-the-century cure-all), a jar of Chesebrough petroleum jelly, and an apparent make-up jar from the Menley & James company.

Taken together, these bottles and jars seem to indicate a turn-of-the-century lifestyle of gatherings and parties, one clouded by concerns for personal appearance along with apparent measures to ensure constitutional regularity and relieve the stresses of that lifestyle. Or as one of my students more succinctly put the hypothesis: “Rich people are full of it.” It would be interesting indeed to learn whether this dichotomy between status as reflected in the European porcelain and concerns for health as reflected in patent medicine bottles is a local or general phenomenon on similar archaeological sites of American wealth.

The mud bank near the confluence of Poquessing Creek and the Delaware River is an extremely complex archaeological site in terms of formation processes. It is both riverine and tidal and both a wet site and alternately a dry land site. In extremely cold winters, ice from the upper Delaware can careen into the river wall. In dry summers the water levels can drop so low that at low tide one can walk nearly halfway across the Delaware River. Below a layer of coal or coke near the surface, with its associated limestone or calcium carbonate, is a thick layer of organic matter, suggesting that the creek was much cleaner before the turn of the century.

Our basic investigations of the site had left us with innumerable questions. What were the artifactual transitions between occupation eras at the estate and the human behaviors within those eras? What is the role of water plants in artifact retention in or movement within the mud bank? What is the exact stratigraphy of the various layers of the mud bank? Could these layers be probed for evidence stretching back to potential Native American occupations of the area? What were the precise movements and disposition of artifacts down the creek and out to the river?

These were all promising areas of inquiry as we wrapped up our final visit to the site in late August 2001. Two weeks later, terrorists attacked the World Trade Center in New York City, and I was called to active duty in the U.S. Coast Guard Reserve for a year and a half.

When I finally returned home and had a chance to return to the creek, I found a new sea wall. The site of much of our mud bank research had been excavated with a large dredge, cleared, and scattered. Today, the bottles and plate fragments we recovered remain locked in a closet next to my office at Penn State Abington. There they await a final determination of whether the very rich really are “full of it.”

From Adventures in Archaeology: The Wreck of the Orca II and Other Explorations. Copyright © 2018 by P. J. Capelotti and published by University Press of Florida. All rights reserved.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.